Don't Short SaaS

The most mispriced trade in technology since March 2020.

$1.2 trillion.

That’s how much market capitalisation evaporated from global software stocks in the first five trading days of February 2026.

Jefferies traders reported “get me out” selling they hadn’t seen since 2008. The Bessemer Cloud Index trades at a 54% discount to its five-year average. Anthropic launched 11 open-source plugins for Claude Cowork, and the market responded by pricing in the death of an entire sector.

The consensus is seductive: AI wins, SaaS loses. Short the incumbents, long the model companies. Simple.

It’s also wrong.

Not completely wrong. Parts of the software universe are genuinely facing existential risk, and we’ll name them. But the market is doing what it always does in moments of structural panic: treating a nuanced, category-specific disruption as a uniform extinction event.

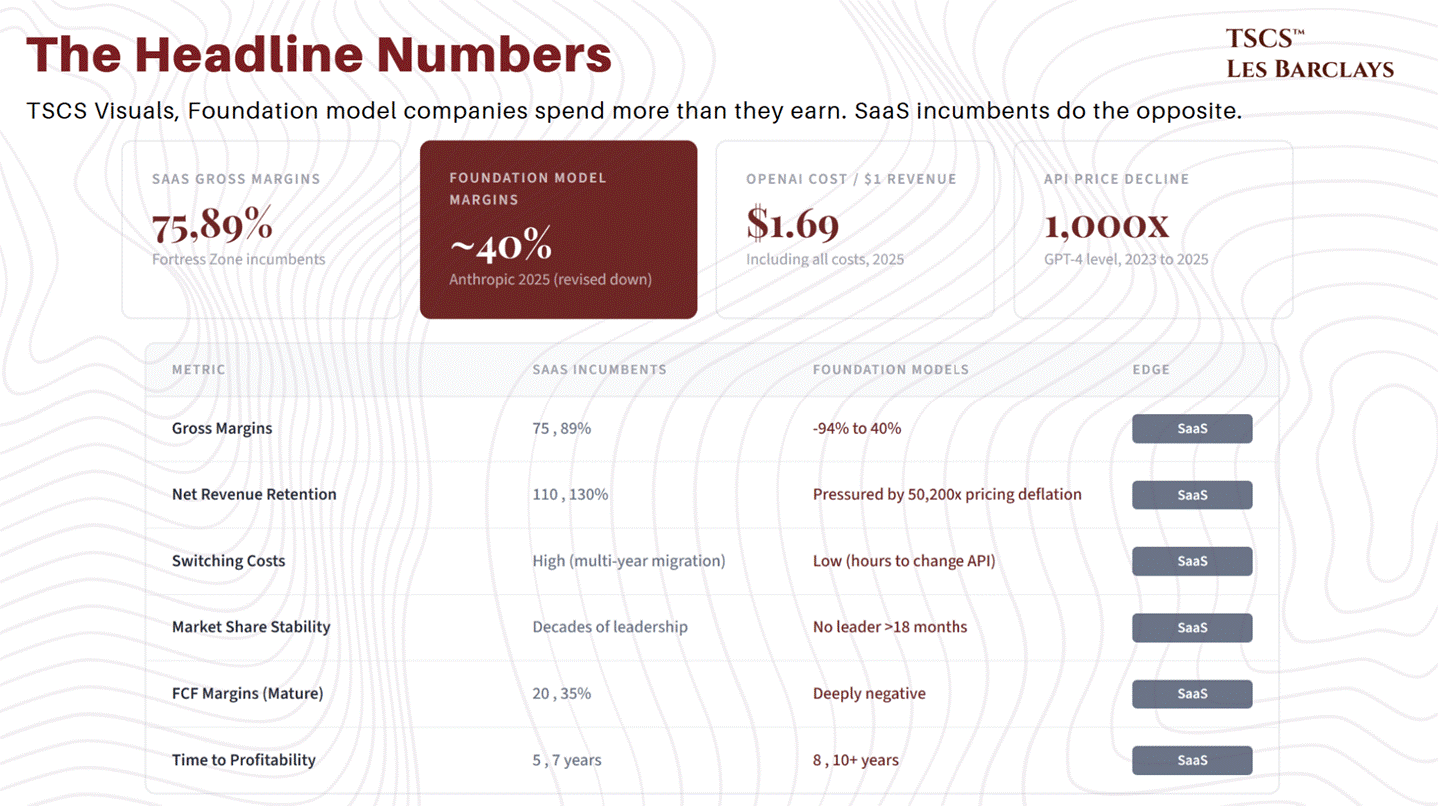

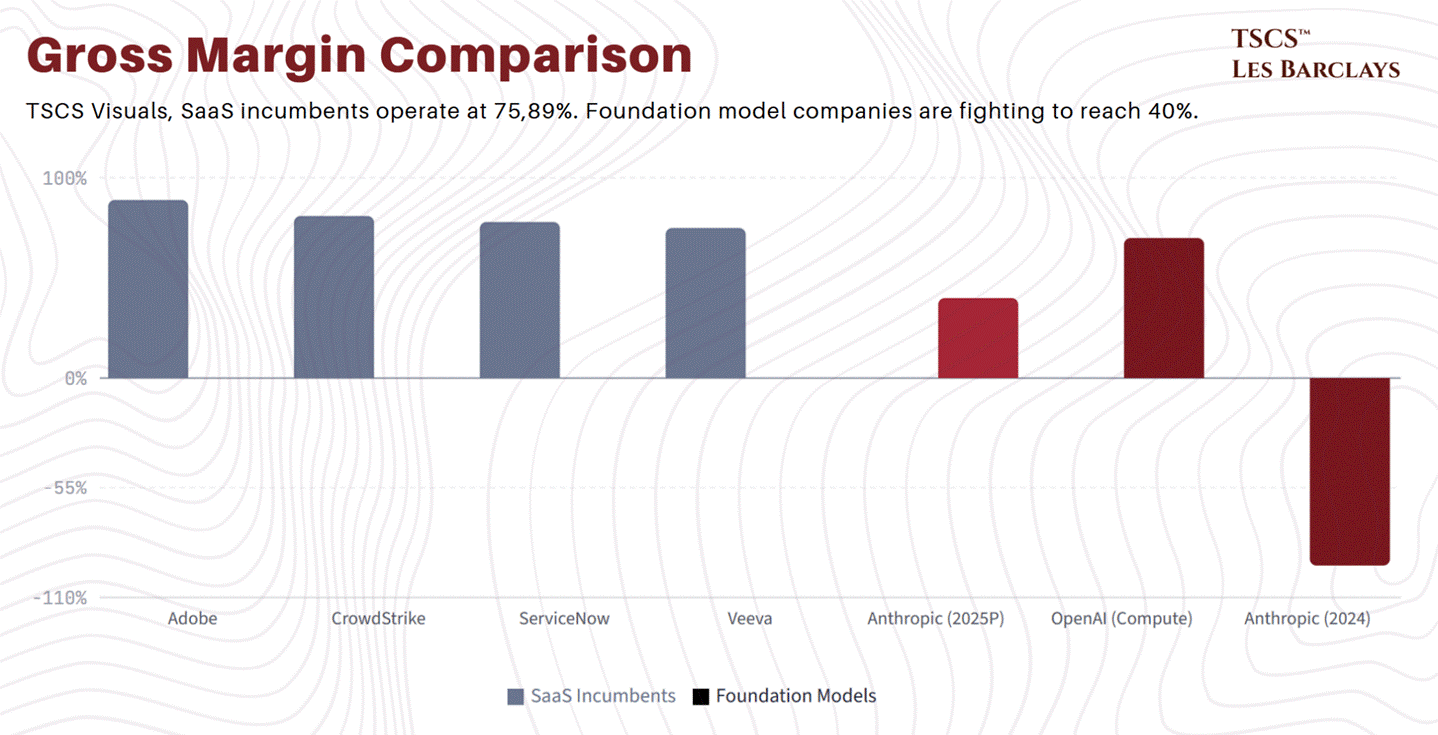

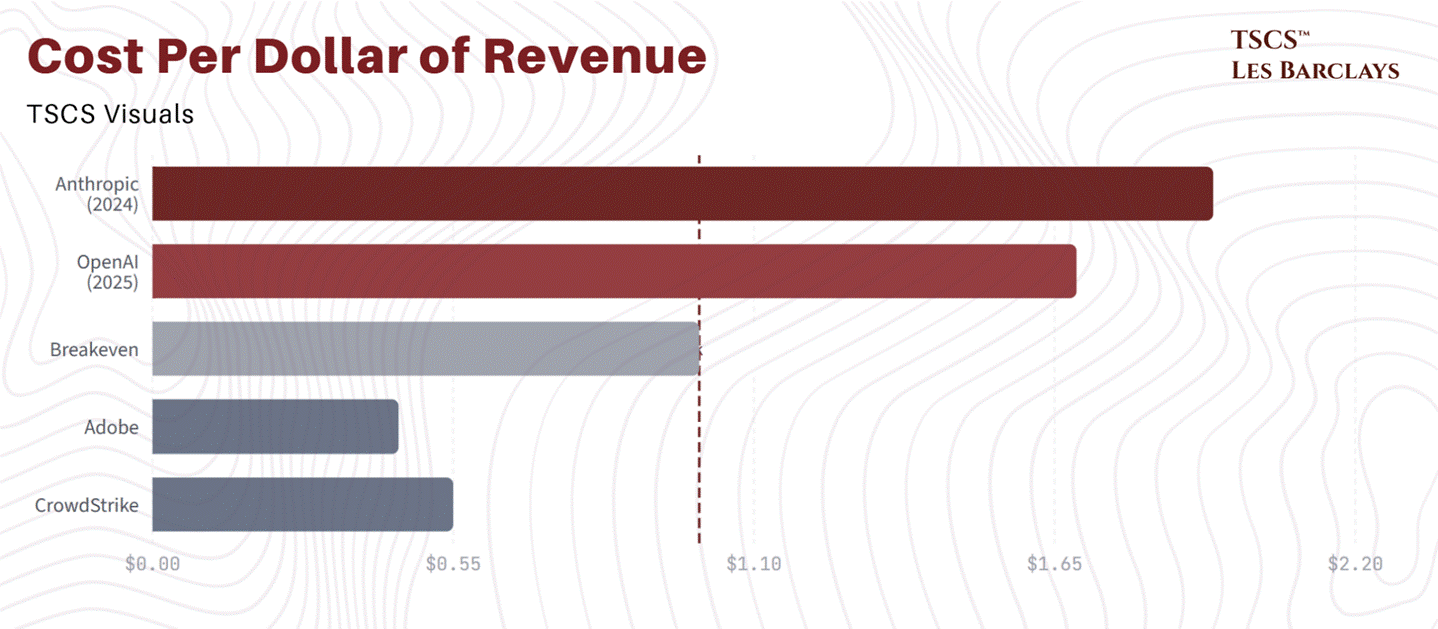

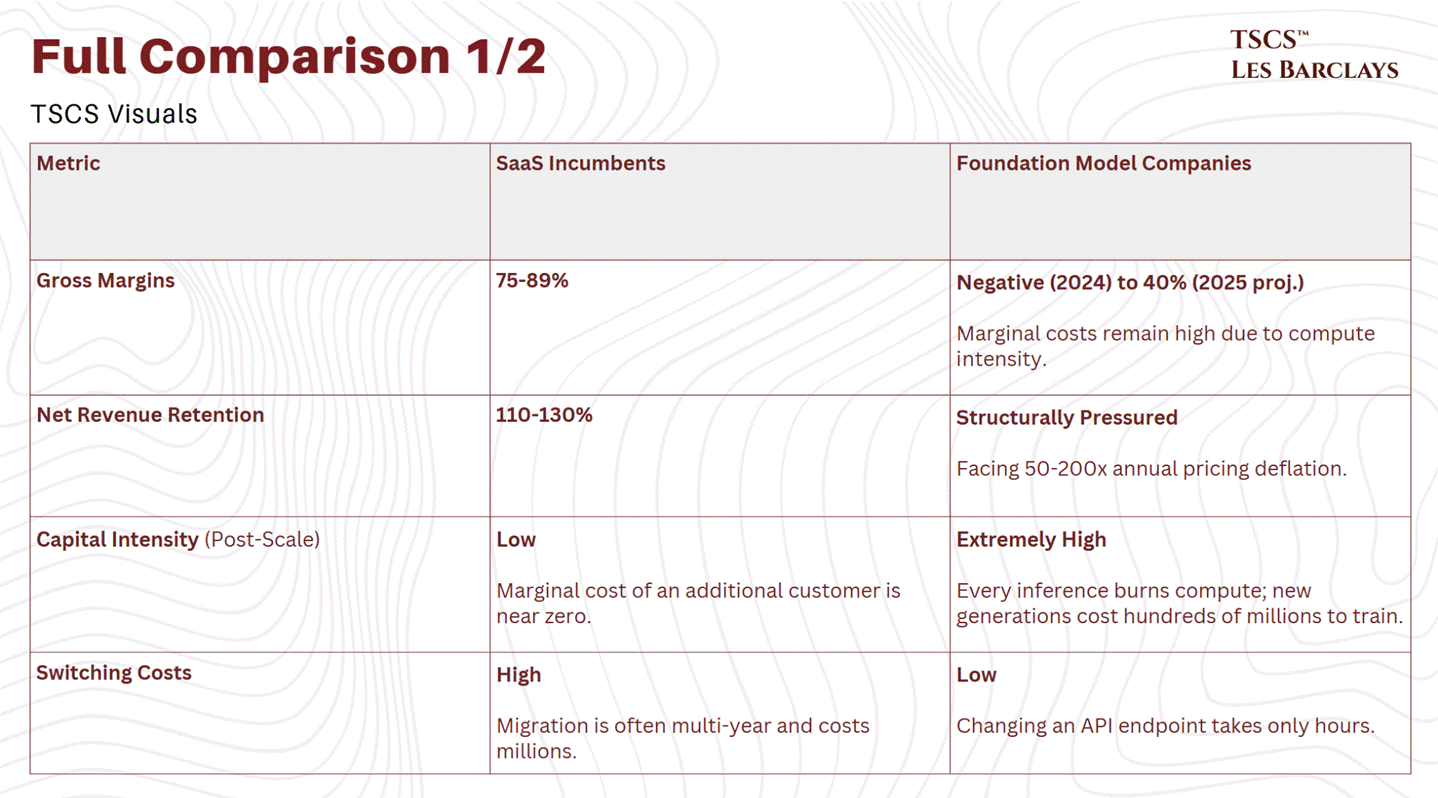

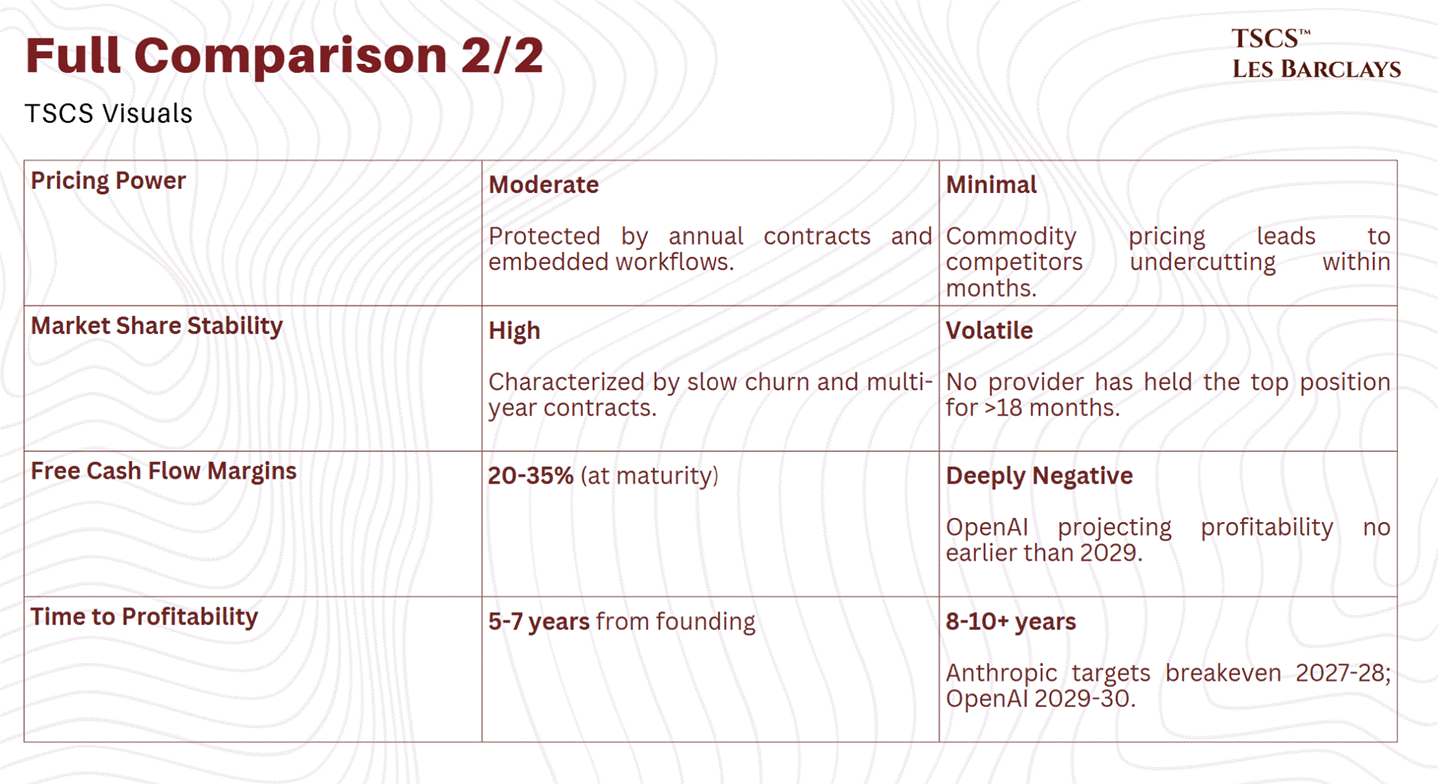

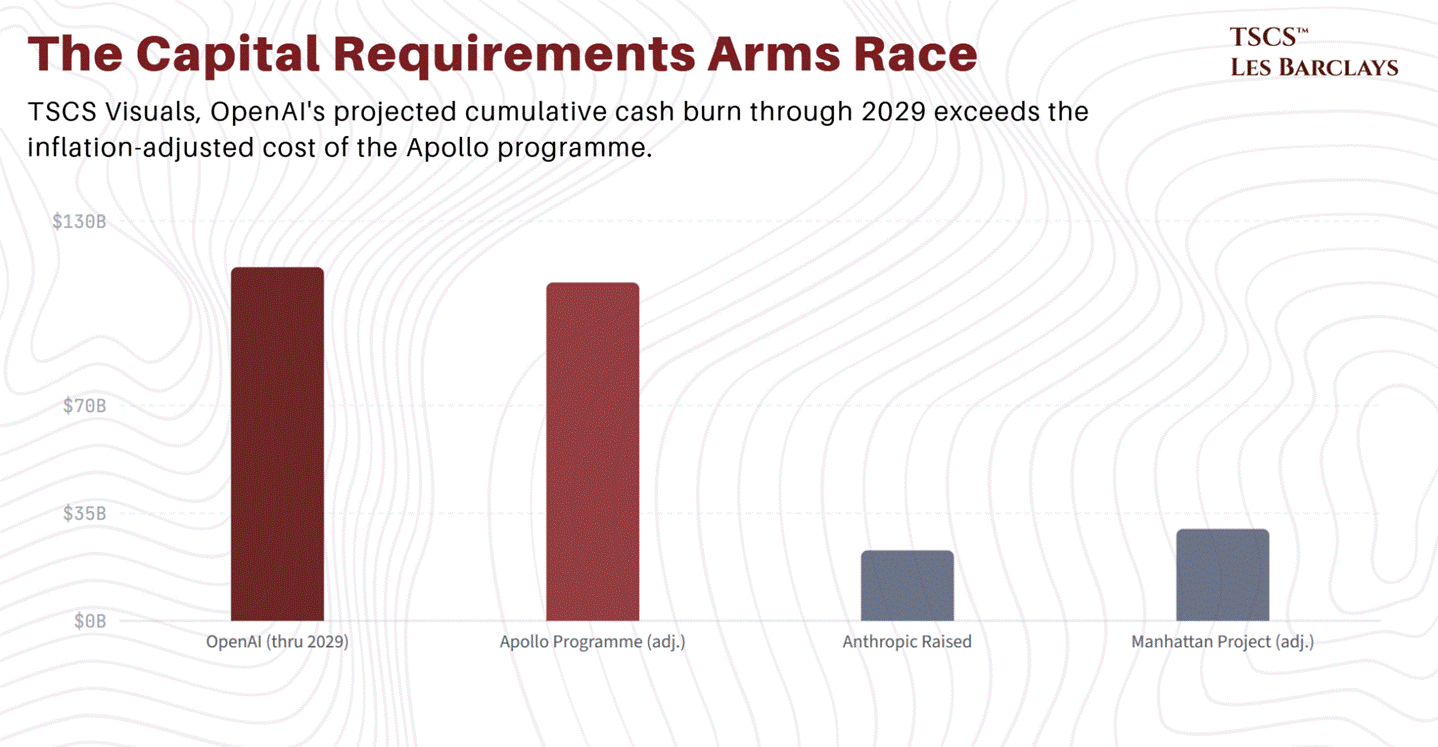

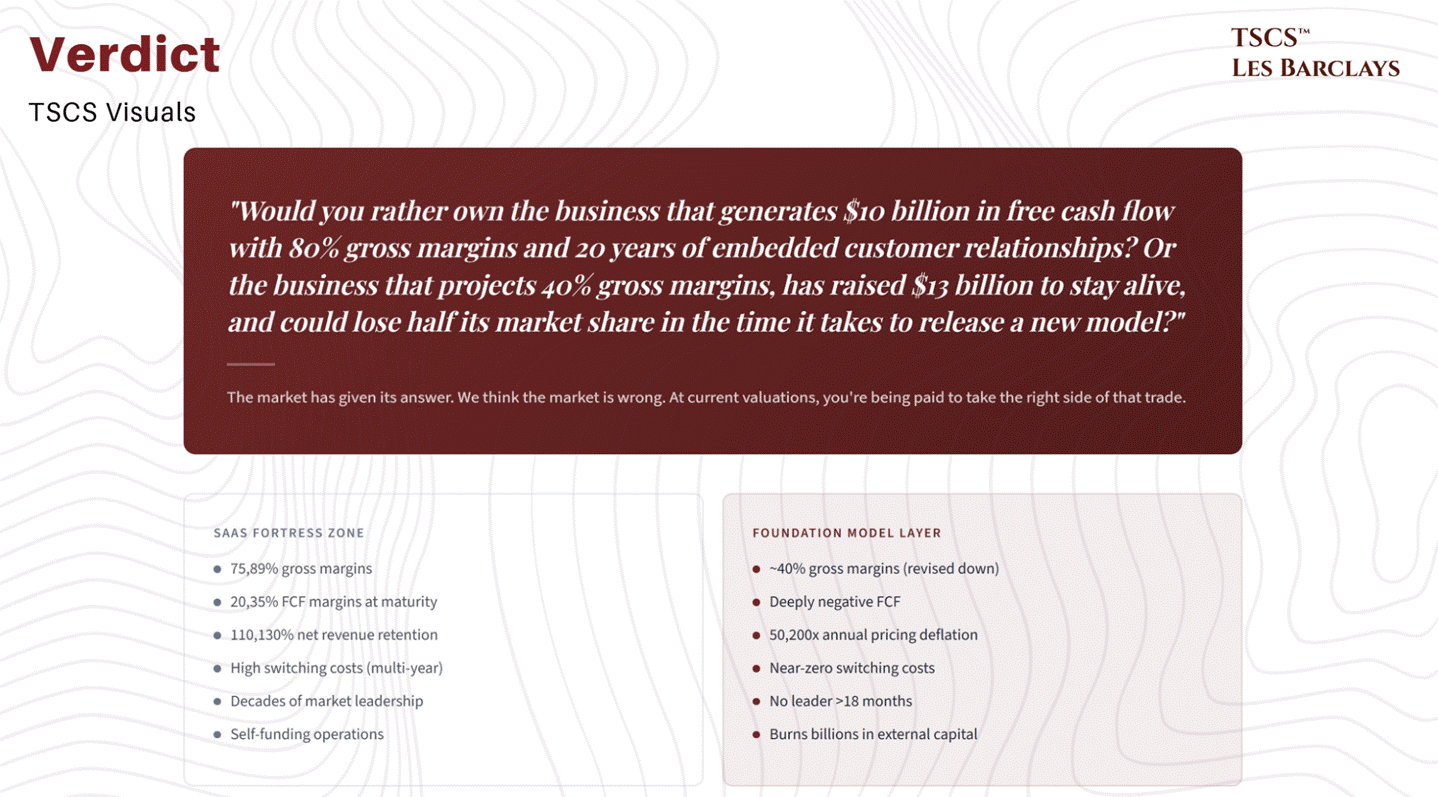

It is selling 80% gross margin businesses to buy 40% gross margin businesses. It is selling companies with 124% net revenue retention to buy companies whose per-unit pricing is collapsing 200x per year. It is selling businesses that generate billions in free cash flow to buy businesses that have collectively burned more capital than the Apollo programme.

Something doesn’t add up. We’ll explain exactly what.

Over 12,000 words and weeks of research, we build the complete framework:

why the model layer is commoditising into infrastructure economics while the application layer retains software economics;

why the deterministic/probabilistic divide is the single most important concept for understanding who survives;

why Jevons’ Paradox means cheaper AI is a subsidy for the right incumbents, not a death sentence; and

where, specifically, capital should be allocated right now.

We name names. Six equity ideas, ranked by conviction, each stress-tested against the framework, with specific entry points, risk factors, and what would make us wrong. This isn’t a “SaaS is fine, don’t worry” piece. It’s a precision instrument for separating the fortress from the wreckage.

This is a joint publication with Les Barclays. When we realised we were independently building the same thesis from different angles, combining forces was the obvious move.

If you’re not yet subscribed to TSCS, now is the time.

We publish institutional-grade equity research, contrarian frameworks, and deep-dive analysis across sectors and market caps. We called the MSTR bear case before Yahoo Finance and Insider Monkey syndicated the thesis.

We published our AI inference economics piece months before the market caught up to the argument. Our Datacenter Bible became the go-to primer on AI infrastructure. We identified Kitwave as an acquisition target, and OEP Partners showed up with a £251 million bid.

Recent work includes our breakdown of AI’s circular financing problem, a full CATL deep dive on the self-funding battery monopolist, our MicroStrategy short thesis (now syndicated across financial media), and our analysis of why the S&P 500’s passive bid is the largest unpriced risk in markets.

That’s what this publication is: original research on the ideas that matter, before the crowd arrives.

If you want institutional-grade research without the institutional price tag, subscribe below.

This piece is a joint publication with Les Barclays, and I want to say something about that directly. Les is one of the writers I actually read. Not skim, not bookmark for later, read. His work on AI Inference Value Capture and Conduit Debt Financing is consistently sharper than what most sell-side desks produce, and when we realised we were independently converging on the same thesis from different angles, combining forces was obvious.'

If you’re serious about equity research and you’re not already subscribed to Les Barclays, you’re leaving edge on the table. I don’t say that lightly and I don’t do paid endorsements. His work speaks for itself.

Let’s get into it.

Section 1: The Catalyst and the Carnage

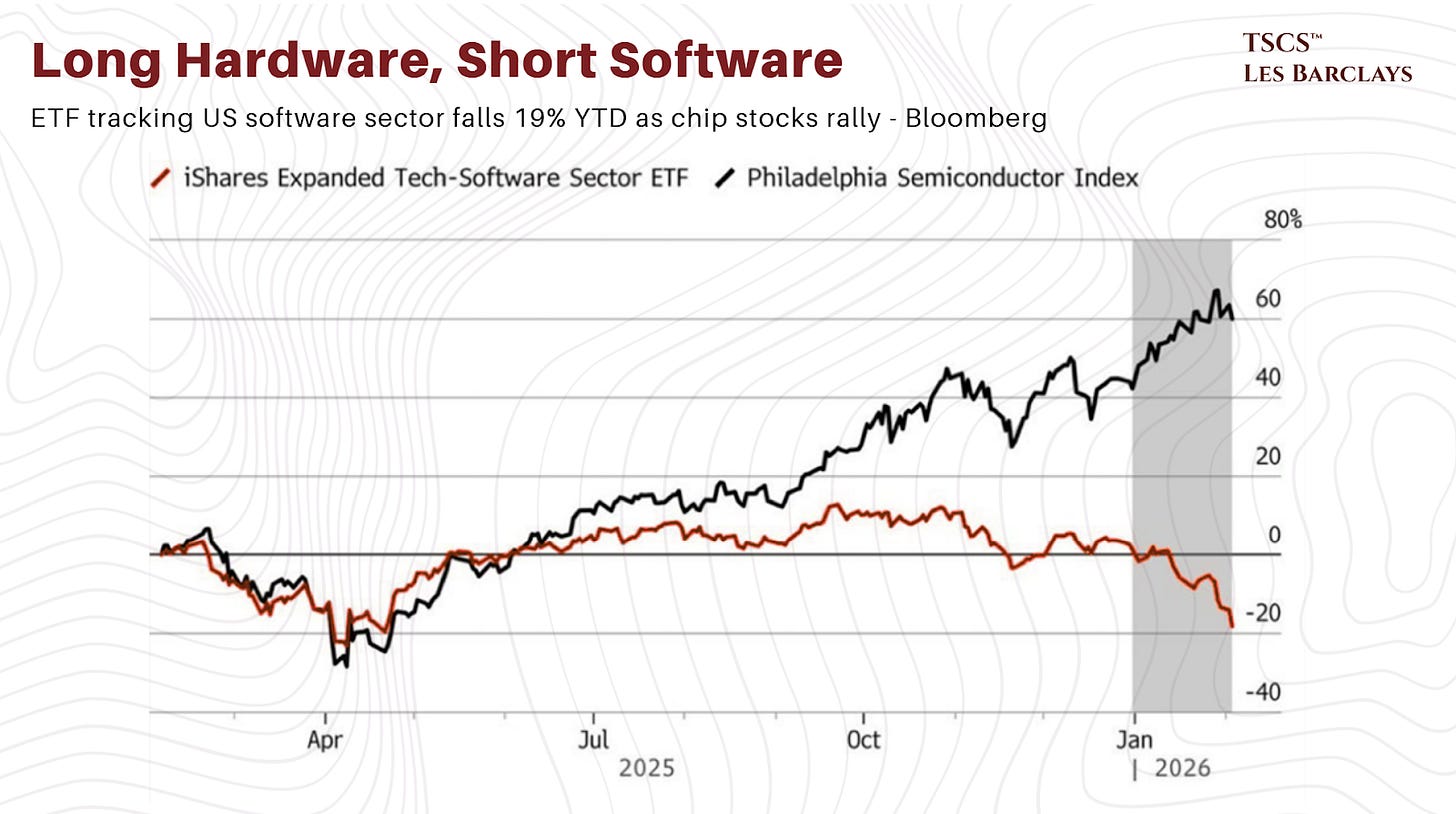

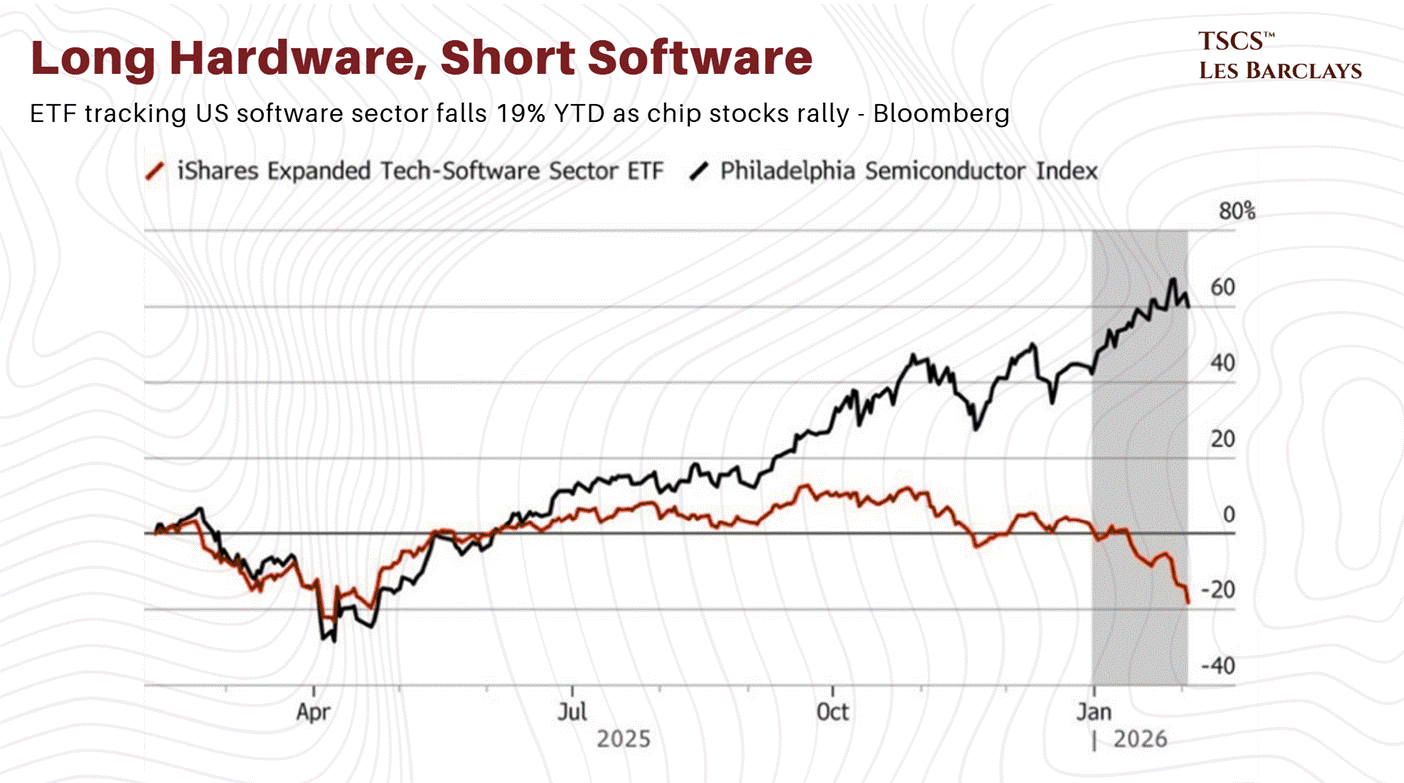

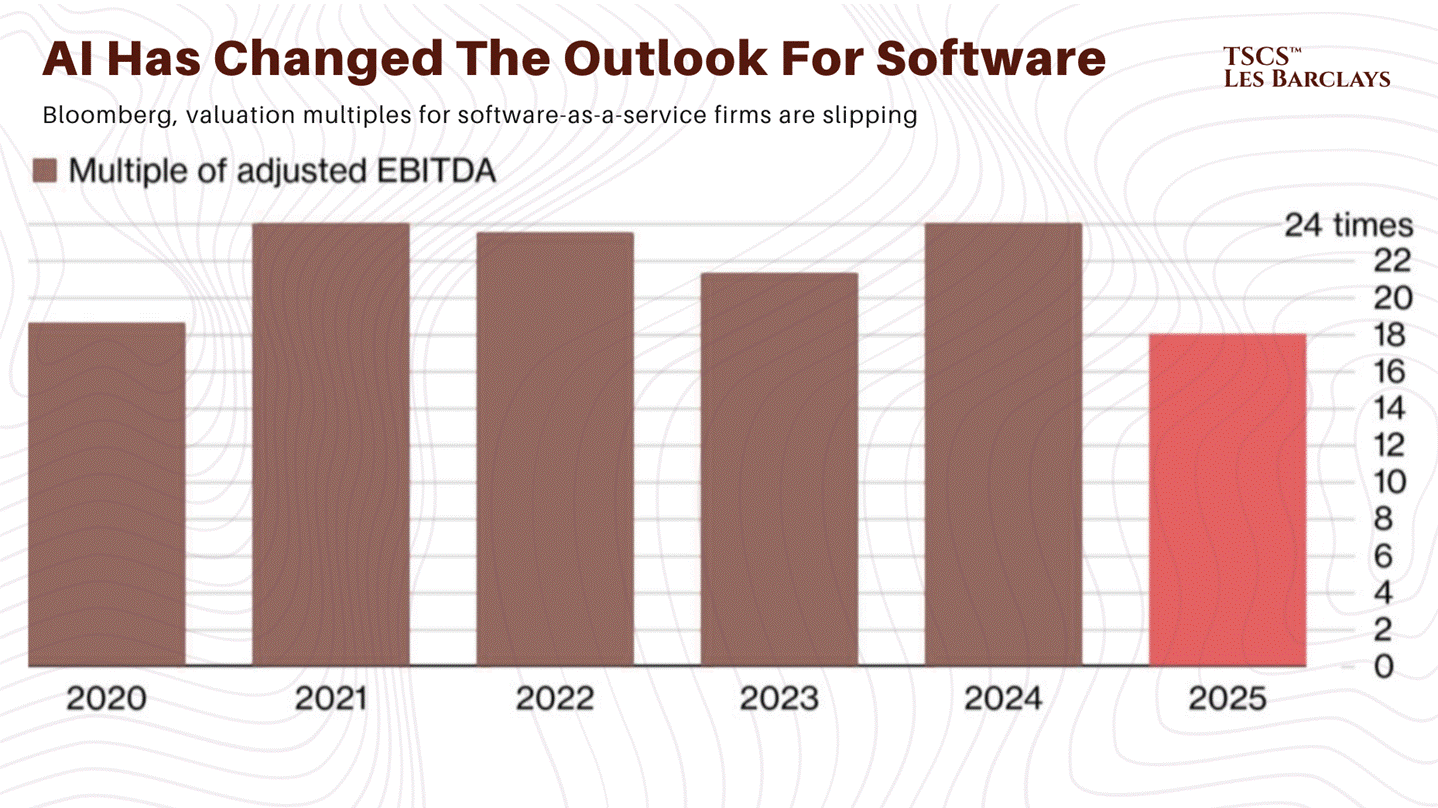

This is the “get lean” moment for software. The divergence between semiconductors and software has reached extremes that defy the historical relationship between these two sectors, which typically move together. Both were supposed to be part of the long AI trade. Now, with the onset of vibe coding and the launch of Claude Cowork, the market is reconsidering whether typical SaaS companies are winners or losers from AI.

The Timeline

January 16: Anthropic launches a feature allowing multiple Claude agents to coexist in a shared workspace and assign tasks to one another. Atlassian (TEAM) and Asana (ASAN) drop roughly 4% as investors realise project management software could be rendered redundant.

January 20: Multiple mid-sized technology and software companies announce freezes on junior hiring, citing AI as the driver of operational savings.

January 26: Dario Amodei publishes his “Adolescence of Technology” essay, signalling that AI could become a “super nation of workers” and potentially win a Nobel Prize within the decade.

January 29: Microsoft announces earnings with weaker Azure guidance. The stock drops nearly 12% the following day, one of the worst sessions in the company’s history. The entire software sector follows: ServiceNow (-11%), Salesforce (-6%).

January 30: Anthropic releases 11 new open-source plugins for Claude Cowork, covering legal (contract review, compliance), finance (analysis and reporting), sales (lead qualification), marketing (campaign management), and customer support (ticket routing).

January 31: Reports confirm nearly 25,000 tech jobs were cut in January alone, one of the highest tallies since 2020.

February 3: The Cowork plugins spark one of the largest single-day declines in software indices. Professional data aggregators sell off sharply: Thomson Reuters (-16%), RELX (-15%), LSEG (-8.5%), Experian (-7.2%).

What Claude Cowork Actually Does

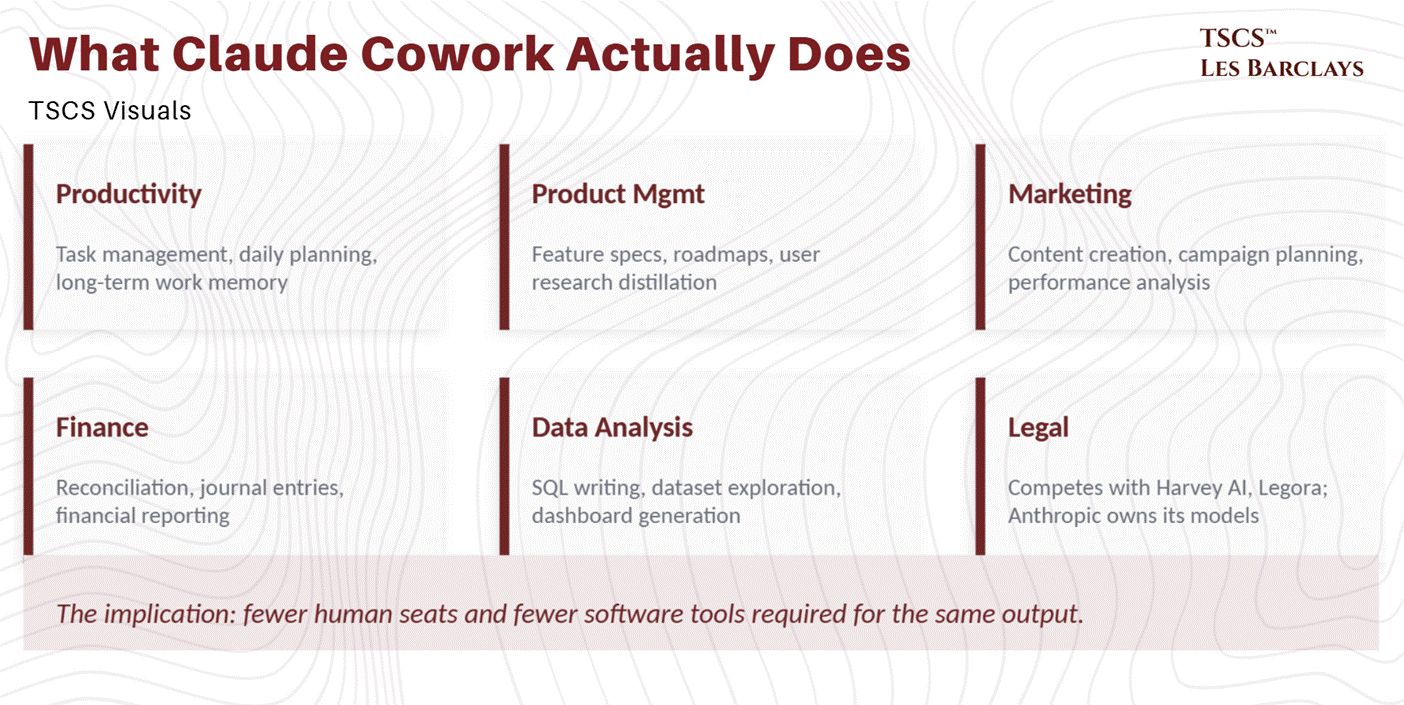

Claude Cowork is Anthropic’s no-code, agentic AI assistant for businesses. The 11 new plugins automate tasks across legal, finance, marketing, sales, product management, and data analysis, work that has traditionally required various specialised software platforms. It collapses a significant portion of that stack into a single AI system that understands context, executes tasks independently, and retains institutional memory.

The plugins are designed around real enterprise workflows. Productivity tools manage tasks, plan the day, and build long-term memory of work context. Product management tools write feature specifications, plan roadmaps, and distill user research. Marketing agents create content, plan campaigns, and analyse performance. Finance tools assist with reconciliation, journal entries, and reporting. Data agents write SQL, explore datasets, and generate dashboards.

The Legal Agent is particularly significant. It competes directly with Harvey AI and Legora, but Anthropic owns its own models, giving it scale and control that startups dependent on third-party models lack. All outputs still require review by licensed attorneys, but the market reaction implies investors are already looking past the disclaimer and pricing in a future where AI shifts from helper to operator. The implication: fewer human seats and fewer software tools required for the same output.

Anthropic appears to be following the vertical integration strategy: own as much of the stack as possible, maintain an internal locus of control. As we argued in our piece on value capture within AI inference, the firms that control the stack and depend least on external infrastructure at any layer are the likeliest to emerge as the durable winners of the AI race. That combination has made Anthropic’s move genuinely unsettling for traditional software firms. For the first time, investors are openly pricing in a shift where AI doesn’t sit on top of existing software but replaces large parts of it altogether.

Feature Moats vs. Platform Moats

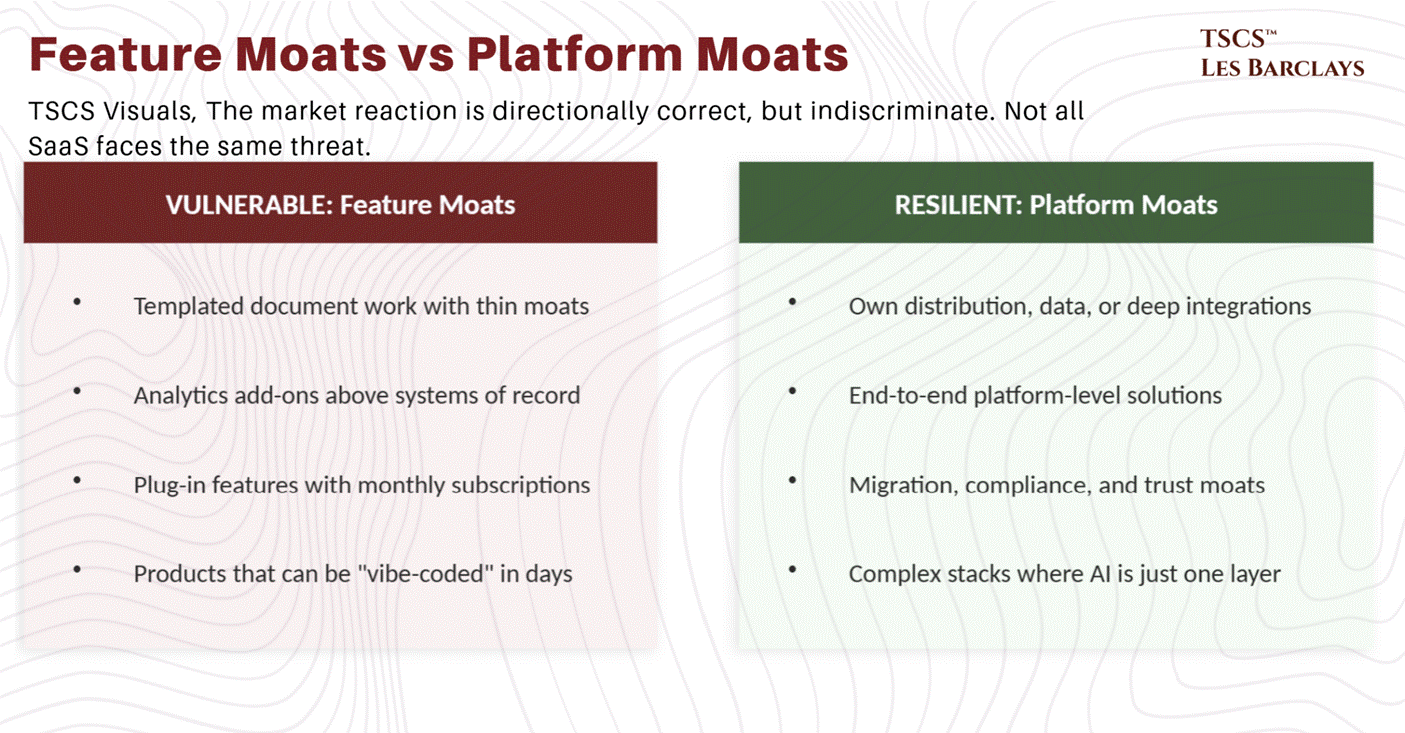

The sentiment is directionally correct, but the market’s response is indiscriminate. AI disruption hits products that are basically templated document work with thin moats. It rewards companies that own distribution, proprietary data, or deep integrations where the agent is just one layer in a complex stack. This is not a total SaaS apocalypse. It is multiple compression for some categories and a secular tailwind for others.

Consider the vibe-coding narrative. The argument that the same enterprises that aren’t downloading and self-hosting open-source alternatives today are suddenly going to spend time, money, and effort vibe-coding their own solutions, and then also host, secure, and maintain them, doesn’t survive contact with reality. There are free open-source replacements for most SaaS products available right now. The reason enterprises still pay for Salesforce is not because they can’t find alternatives. It’s because migration, integration, compliance, and institutional trust are worth more than the subscription fee.

It isn’t just Claude. It’s the expectation that these capabilities become cheap and embedded everywhere. The winners will be the tools with distribution, workflow depth, and trust, not just raw capability. The moral is straightforward: if your SaaS doesn’t have a wide moat and can be vibe-coded in minutes (or even days), your SaaS is toast. Someone will eat your lunch by doing it better, faster, and cheaper. But the transition won’t be instantaneous. Companies won’t abandon legacy SaaS overnight when there’s no trust infrastructure around the replacement.

Where the Damage Actually Lands

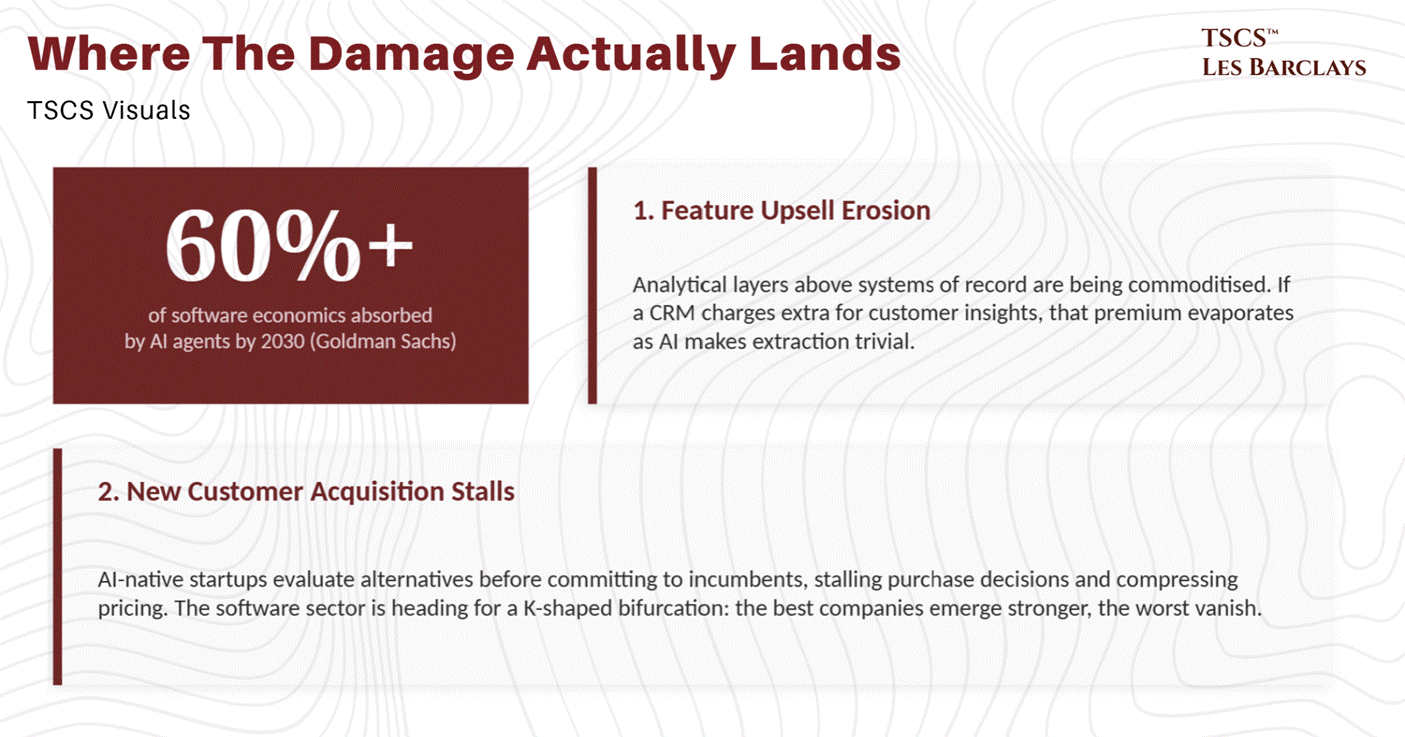

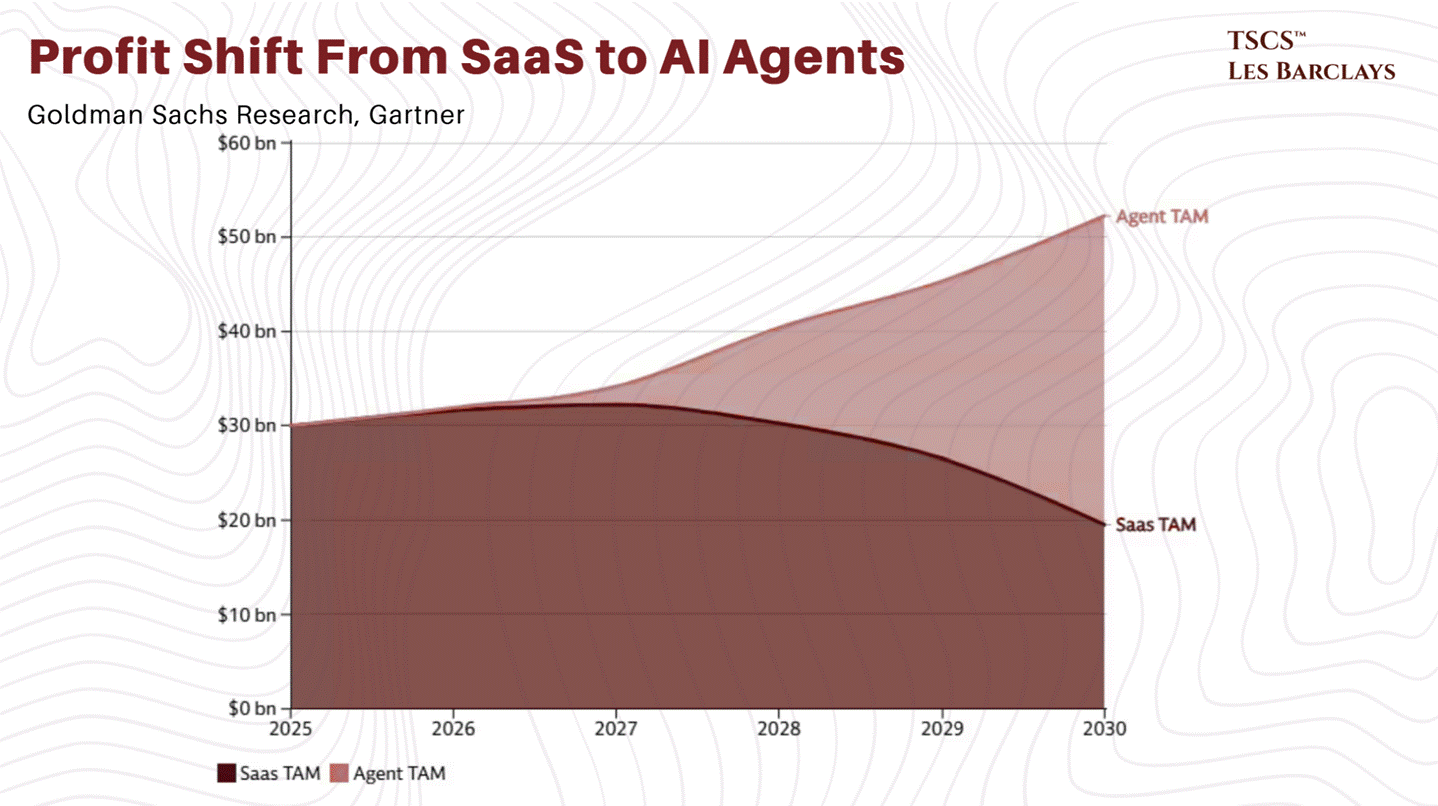

Goldman Sachs projects that AI agents will account for over 60% of software economics by 2030, absorbing dollars that currently flow to classic SaaS seats. Most deployments today are still chatbots wired to LLMs; the stronger agentic patterns remain proofs of concept or internal pilots. The stack needs a stable platform layer plus guardrails for identity, security, and data integrity, and broad standardisation is at least 12 months away.

The real turmoil in software is not the loss of existing customers. A Fortune 500 with its data already embedded in Salesforce or Workday is not going to rip it out and replace it with a vibe-coded internal tool. The real damage hits in two places.

First, the upsell of additional features that add analytics, insights, or ease-of-use on top of the core platform. If a CRM upcharges your subscription for customer insights, that feature becomes less valuable every quarter as AI makes it trivial to extract those insights independently. As long as you can export the data, the analytical layer above the system of record is increasingly commoditised.

Second, new customer acquisition. AI-native startups will evaluate alternatives before committing to incumbent platforms, stalling purchase decisions and compressing pricing. The real test will come down to whether you’re selling a feature or a platform. SaaS companies selling plug-in features with a monthly subscription will get replaced. Companies providing end-to-end platform-level solutions will not only survive but may see unit economics improve as they deploy AI to cut their own costs. The software sector is heading for a K-shaped bifurcation on steroids: the best companies emerge stronger, the worst vanish or miraculously reinvent themselves.

The Private Markets Angle

Most analysis of the SaaSacre has focused on public markets, which is understandable but incomplete. The private markets side is just as important, and arguably more fragile.

VC-backed software companies face a particularly grim set of constraints. They can’t raise more rounds, can’t sell to PE, and can’t IPO. They have roughly 12 months to figure out how to add AI to their products, and whether that saves them remains to be seen. The key for these companies is simple: be cash-flow positive so you can live to fight another day.

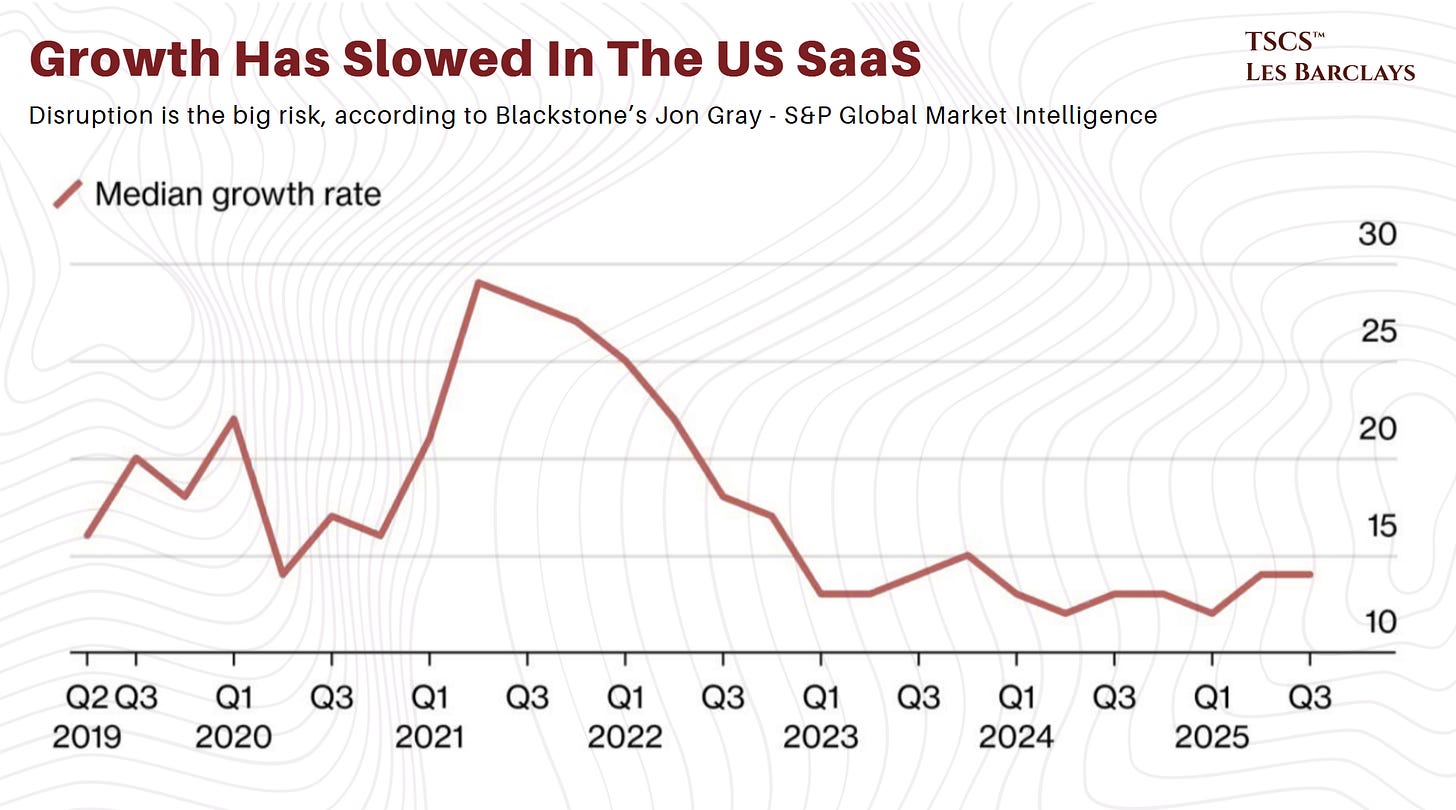

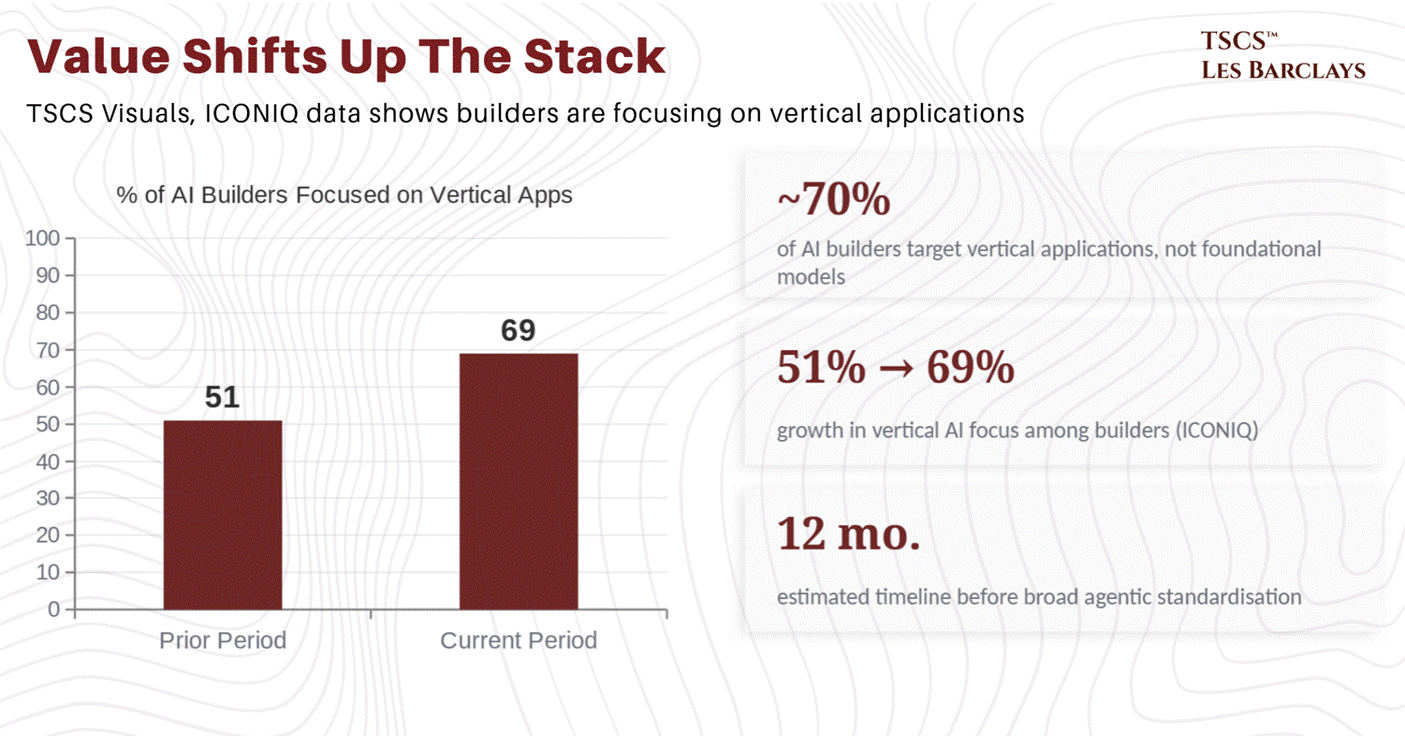

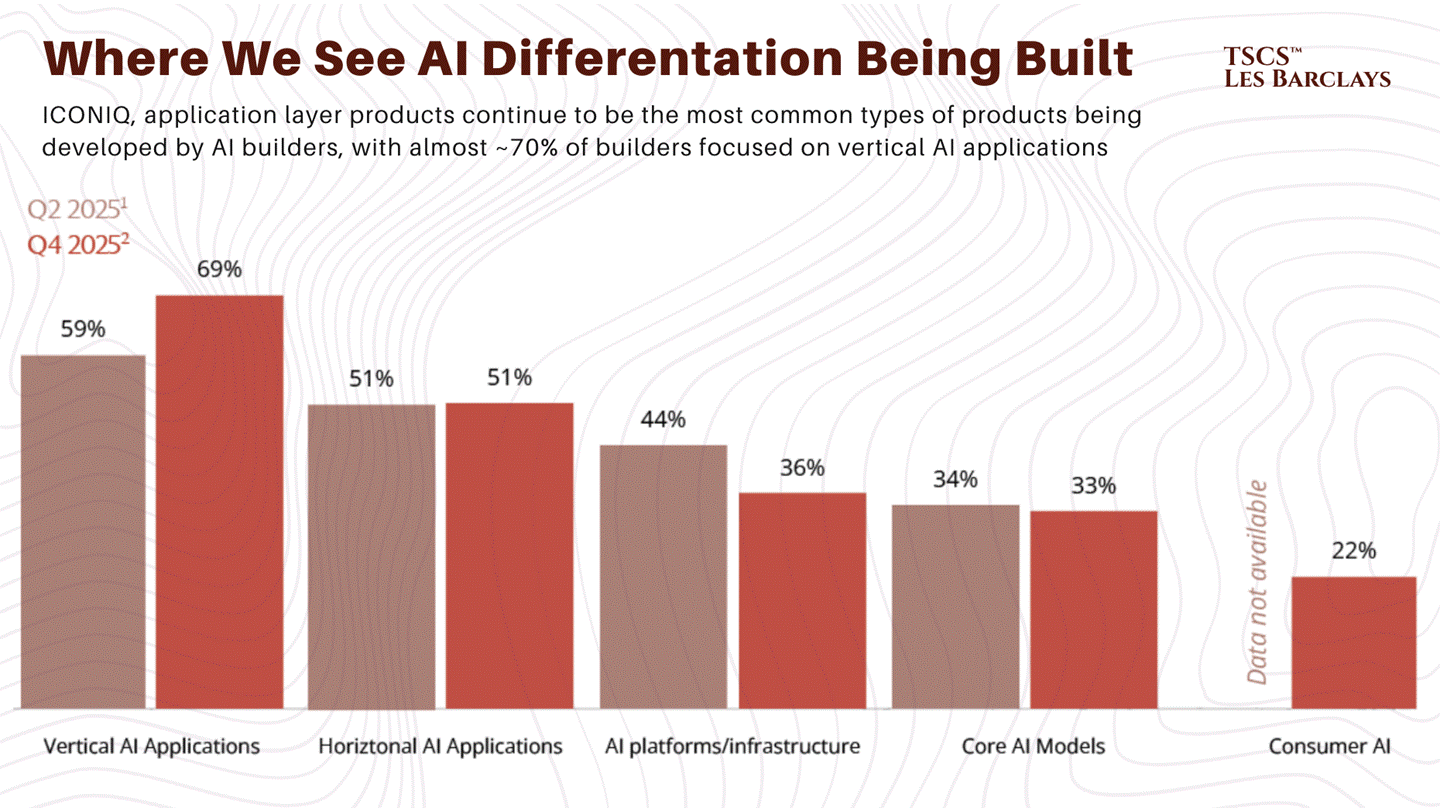

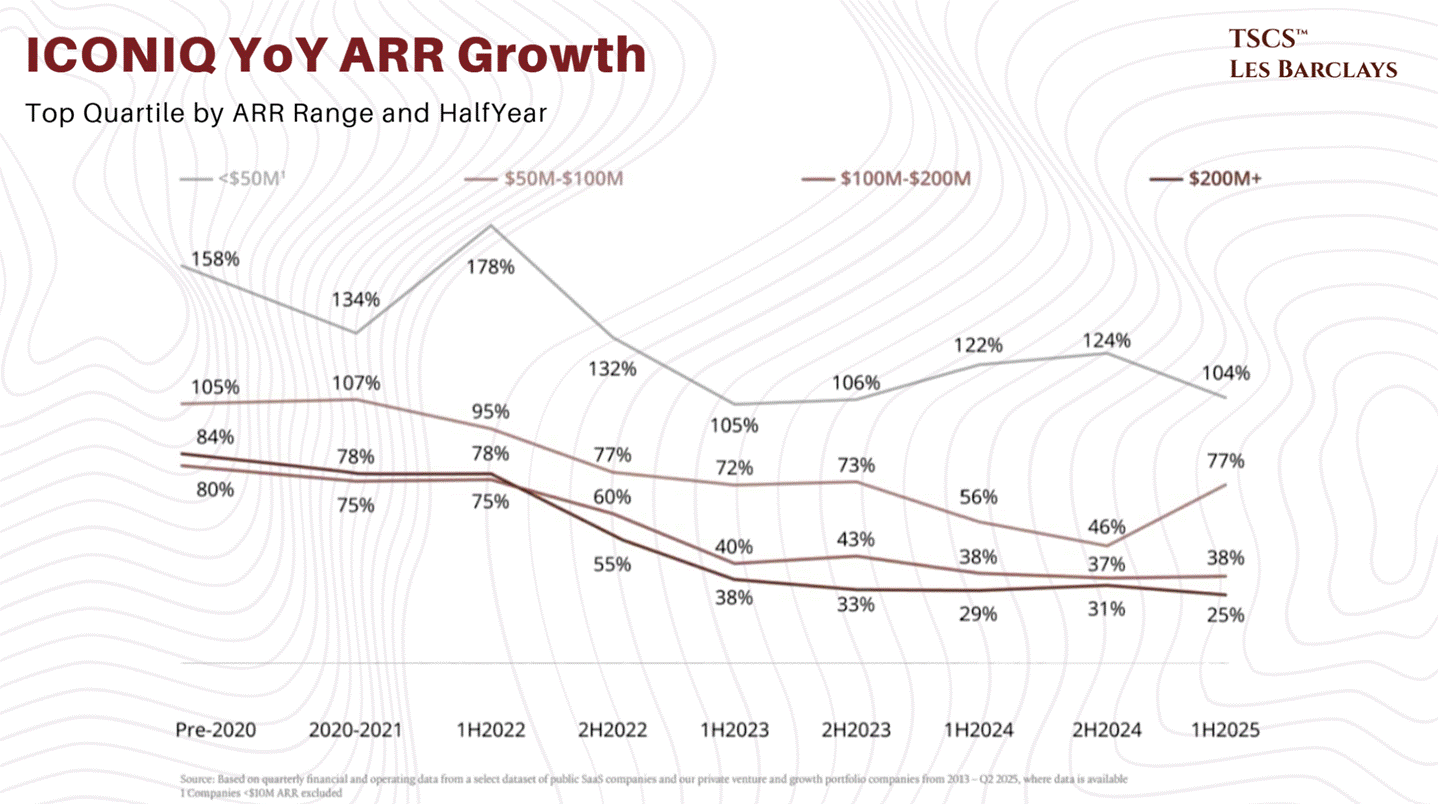

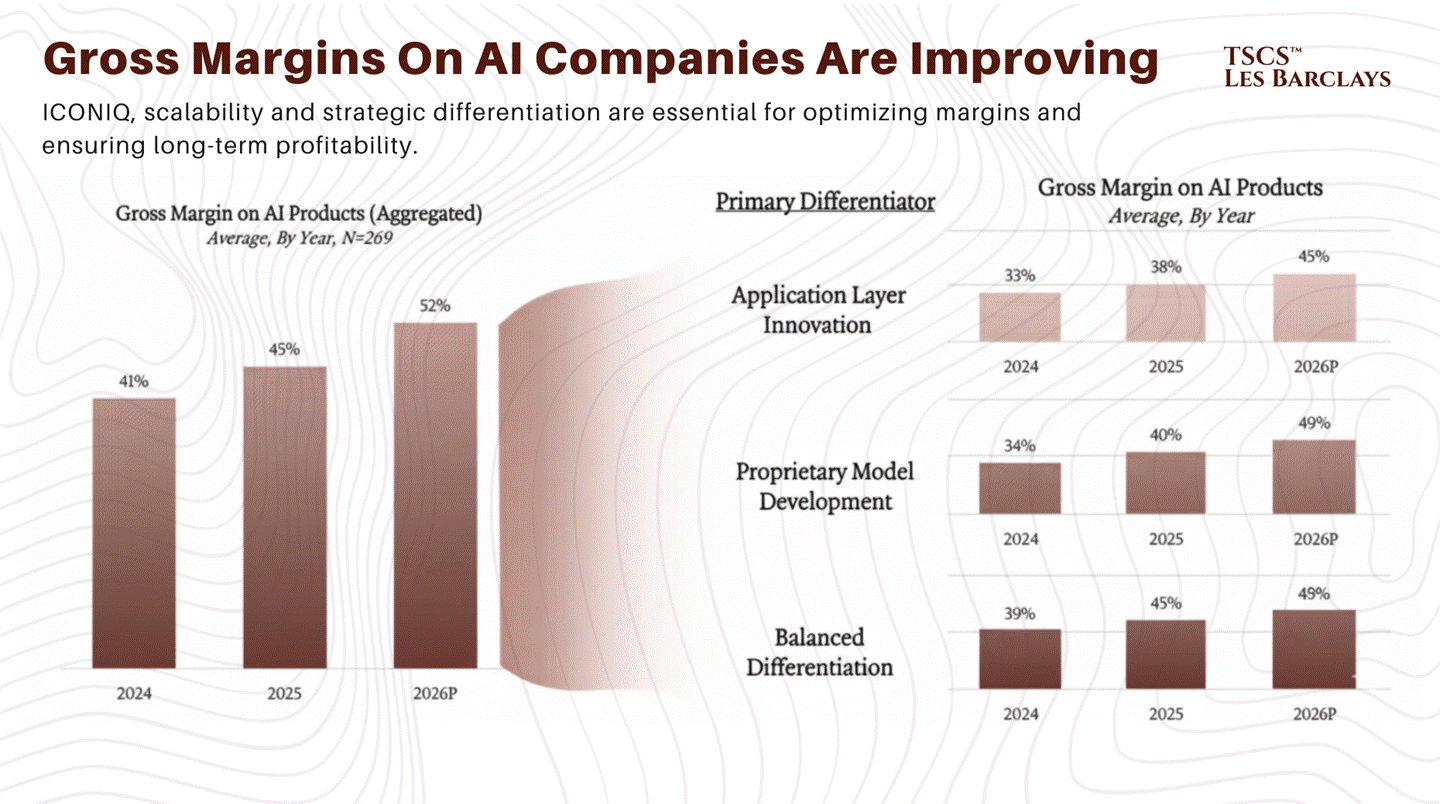

The ICONIQ data confirms what the market is missing. Nearly 70% of AI builders are focused on vertical applications, not foundational models. Vertical AI applications grew from 51% to 69% of what builders are creating.

These are companies building on top of models, not competing with them. The model layer is commoditising exactly as expected, which means the value is shifting up the stack to whoever owns the data and workflows. That’s the SaaS incumbents everyone is panic-selling.

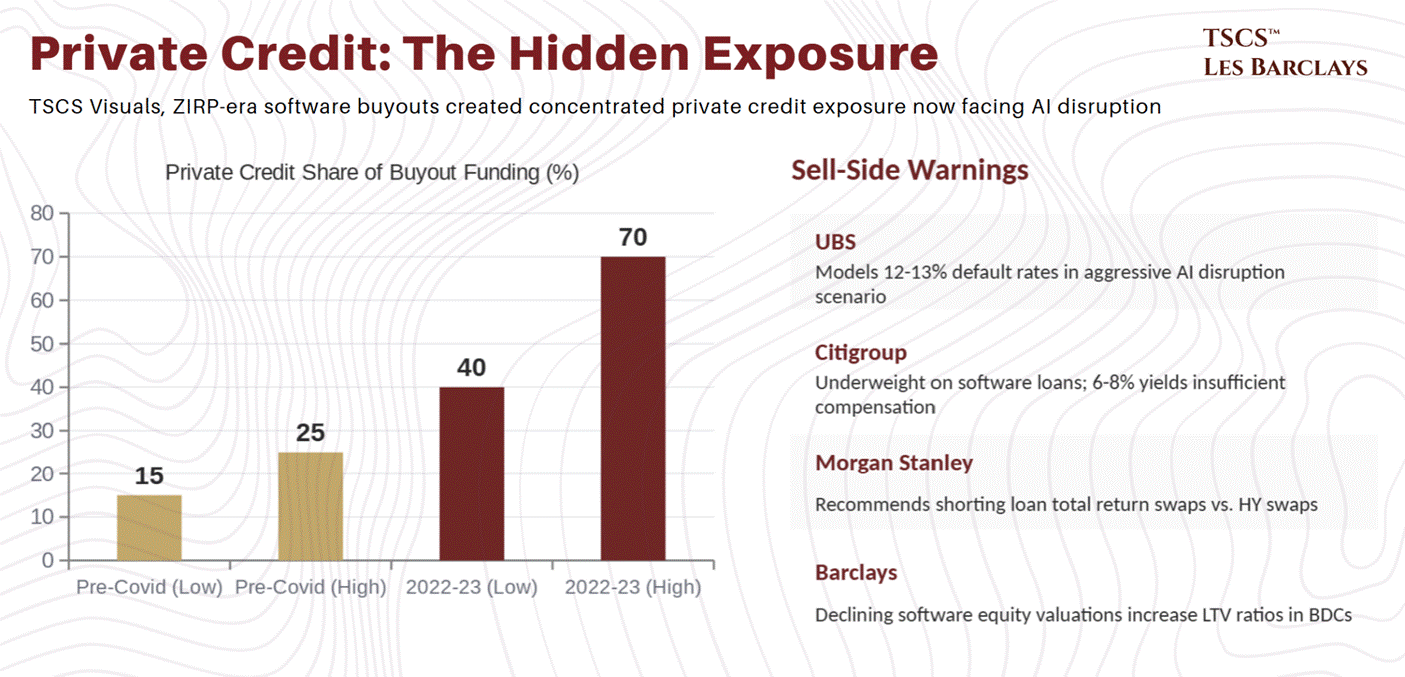

The private credit exposure is where this gets genuinely concerning. As Matthew Brooker noted in Bloomberg, the vintage of software acquisitions made in the ZIRP era presents a serious problem. Many buyouts were executed at peak valuations just after Covid, and rising interest rates shut down the traditional syndicated loan market. Private credit stepped into the breach, with direct lenders jumping from 15-25% of buyout funding pre-Covid to 40-70% in 2022-2023, according to UBS credit strategist Matthew Mish.

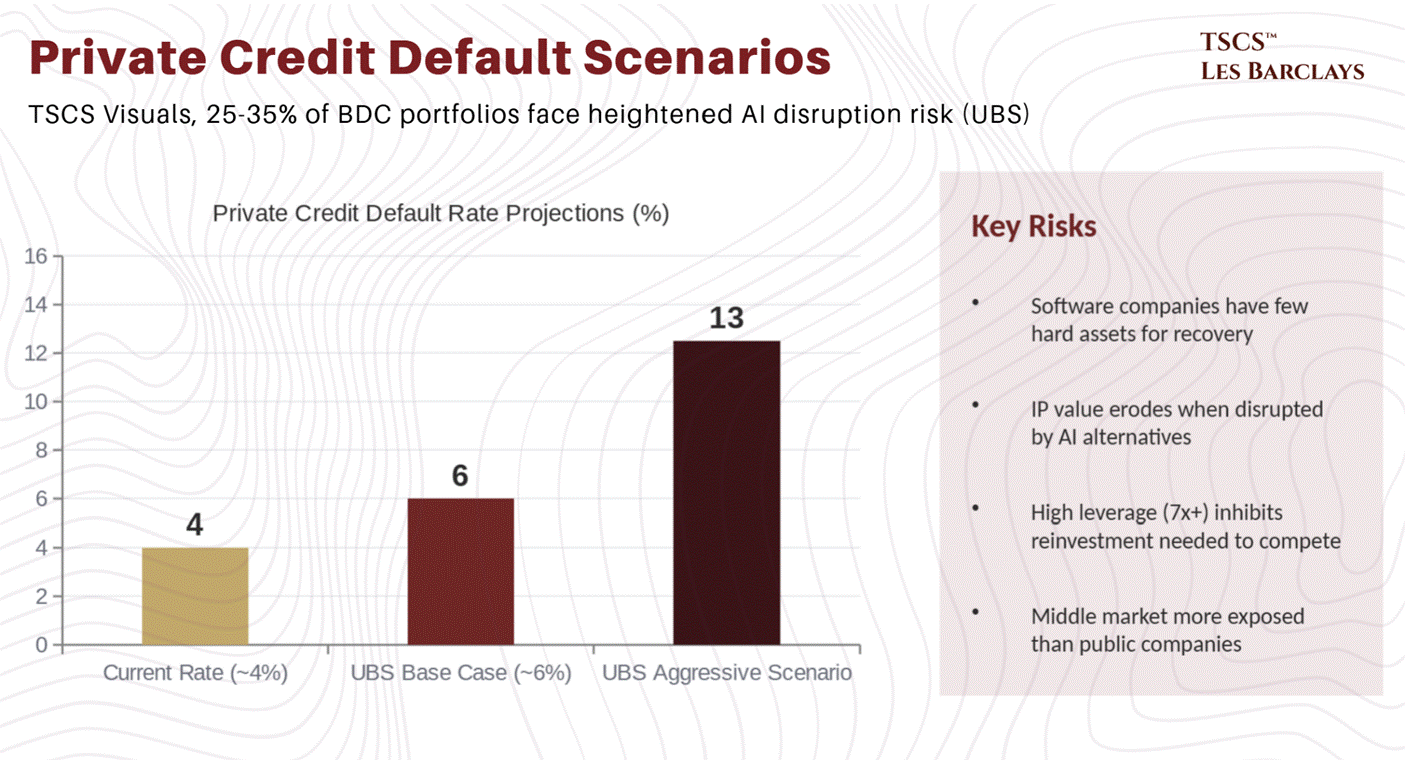

That concentration means private credit is now disproportionately exposed to AI disruption. Mish estimates 25-35% of BDC portfolios face heightened threats, and forecasts private credit default rates rising roughly 2 percentage points this year to around 6%.

The sell-side is paying attention. UBS models an “aggressive AI disruption” scenario with defaults reaching 12-13% in private credit. Citigroup has initiated an underweight on software loans, citing 6-8% yields as insufficient compensation. Morgan Stanley is recommending shorting loan total return swaps versus high-yield swaps on the back of higher software exposure and worse convexity. Barclays notes that declining software equity valuations are increasing loan-to-value ratios across BDC portfolios, with potential obsolescence of some borrowers introducing material asset quality risk.

For years, software companies with high EV multiples, strong recurring revenue, and solid retention metrics were easy to lever at 7x or higher. That trade is breaking. PE will struggle to exit many legacy SaaS platforms acquired at peak multiples in 2021. For private credit lenders, the risk isn’t only higher defaults but lower recoveries. Software companies have few hard assets, and their IP isn’t worth much when it’s being disrupted. The high leverage inhibits reinvestment precisely when these companies need to spend aggressively to stay competitive.

It’s worth noting that these dynamics are probably more severe across the middle market than in public companies. Not all PE and private credit firms are created equal, but the trend of AUM accruing to the most scaled players isn’t stopping.

Section 2: The AI-Native Advantage (and Its Limits)

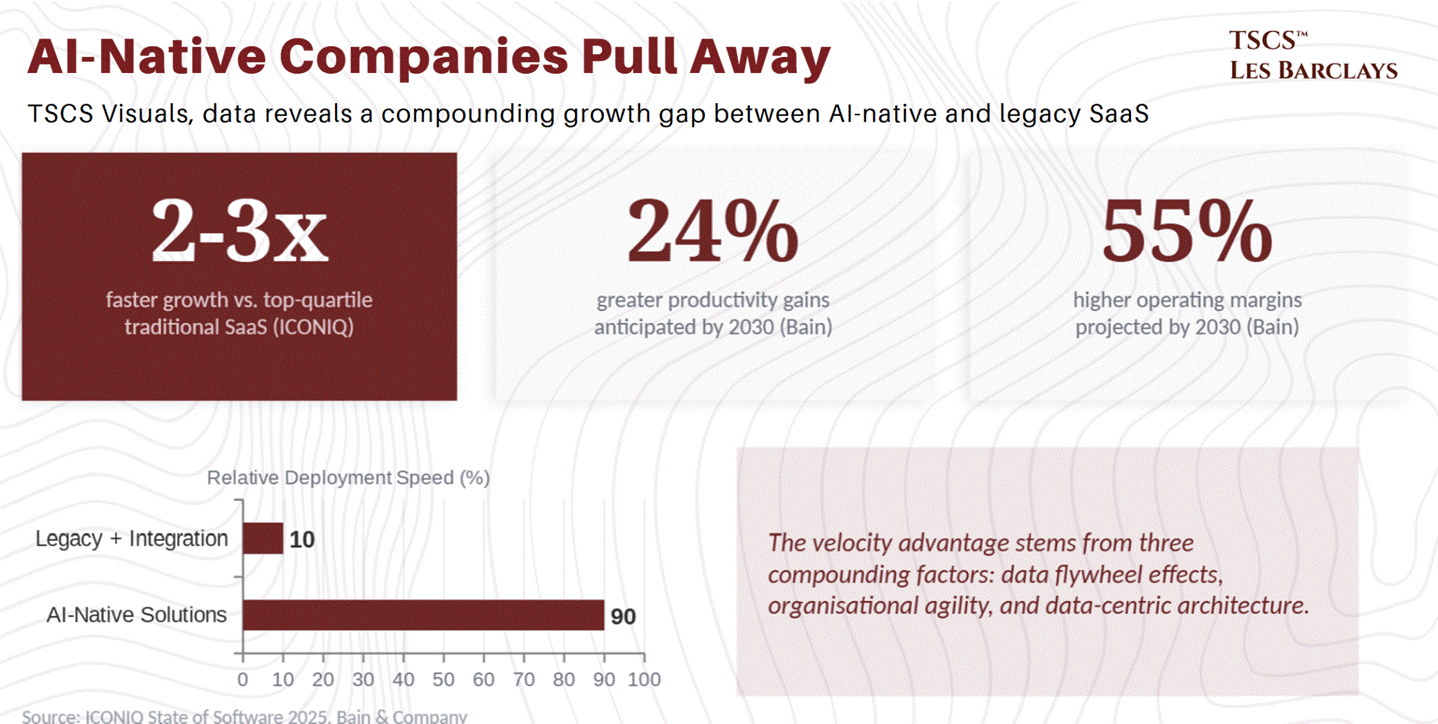

AI-native companies are growing 2-3x faster than top-quartile traditional SaaS benchmarks (ICONIQ).

The gap compounds. Every customer interaction becomes training data that improves the product. Better products attract more users, which generate more proprietary data. Legacy companies bolting AI onto existing workflows can’t replicate this because their architecture wasn’t designed to capture interaction data systematically.

Companies scaling AI across multiple workflows anticipate 24% greater productivity gains and 55% higher operating margins by 2030, with AI-native solutions deploying 90% faster than legacy systems requiring integration work.

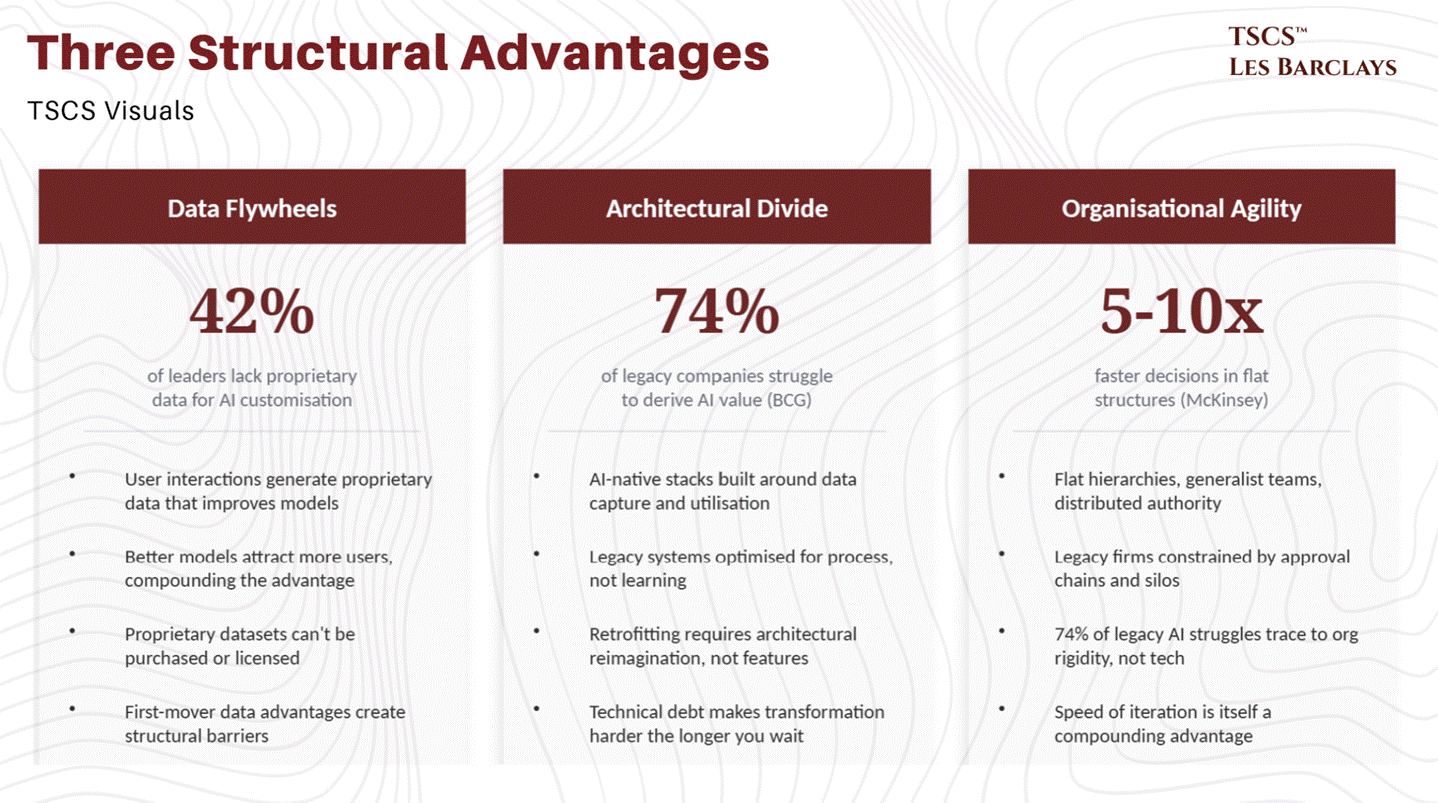

The velocity advantage is real, and it stems from three compounding factors: data flywheel effects, organisational agility, and data-centric architecture.

The Structural Advantages

Data flywheels are the most powerful of the three. Unlike brand or network effects, data flywheels compound exponentially: user interactions generate proprietary data, that data improves AI models, better models attract more users. Proprietary datasets (transaction histories, usage patterns, domain-specific content) can’t be purchased or licensed. First-mover advantages in data collection create structural barriers that money alone can’t buy.

And yet 42% of business leaders report they don’t have enough proprietary data to effectively train or customise AI models.

The architectural divide is equally important. AI-native companies design their entire stack around data capture and utilisation: outcome interfaces, agent orchestration, and systems of record, all built modularly. Legacy companies are optimised for process efficiency, not data collection or feedback loops. The systems were built to do a thing.

AI needs them to learn from doing the thing. Retrofitting data flywheel capabilities onto workflow-centric architecture requires not feature additions but architectural reimagination. Technical debt and integration complexity make that transformation exponentially harder the longer you wait.

Organisational agility compounds the gap. AI-native startups operate with flat hierarchies, generalist teams, and distributed decision authority. McKinsey research shows flat structures enable 5-10x faster decision-making. Legacy companies are constrained by hierarchical approval chains and functional silos. BCG research confirms the pattern: 74% of legacy companies struggle to derive AI value, largely due to organisational rigidity, not technology gaps.

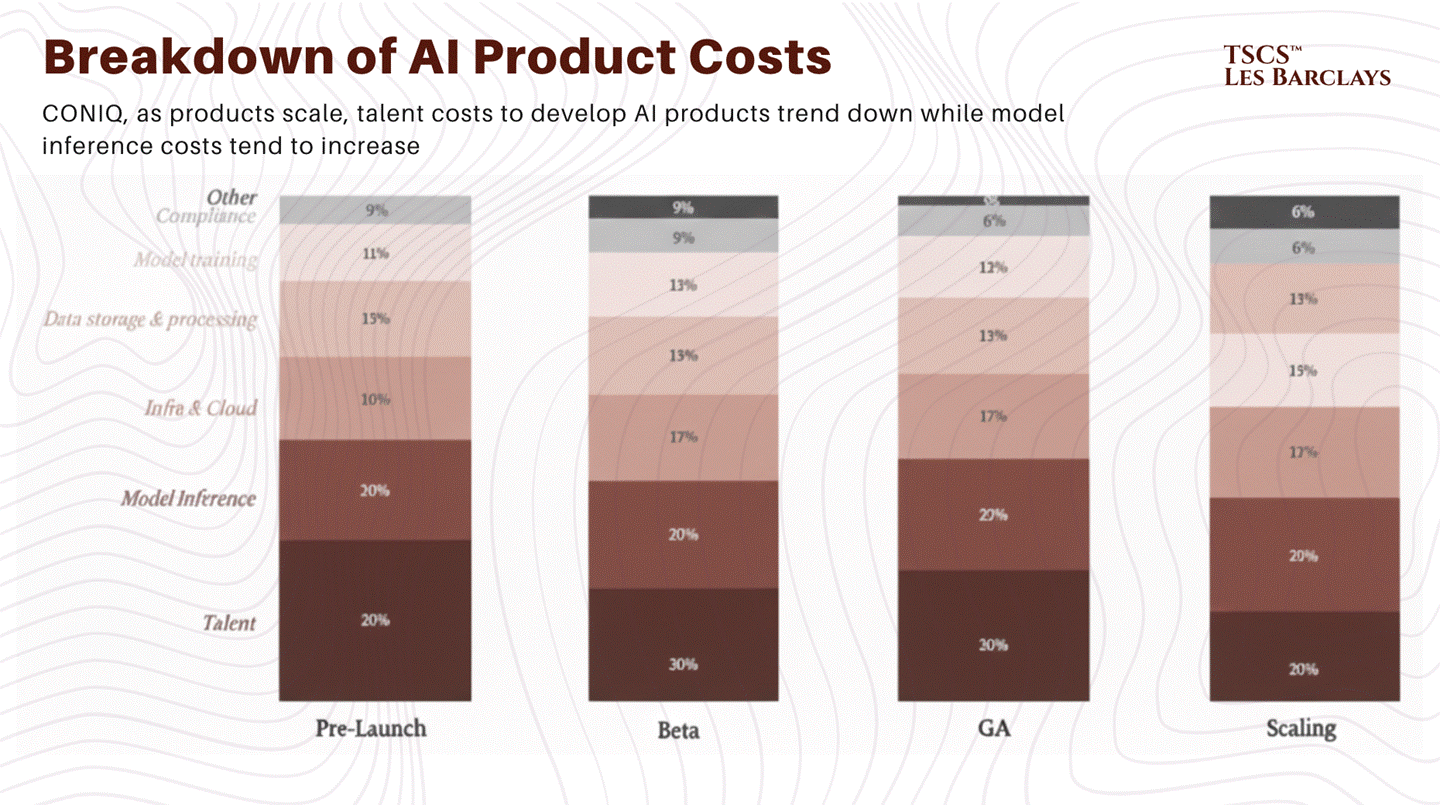

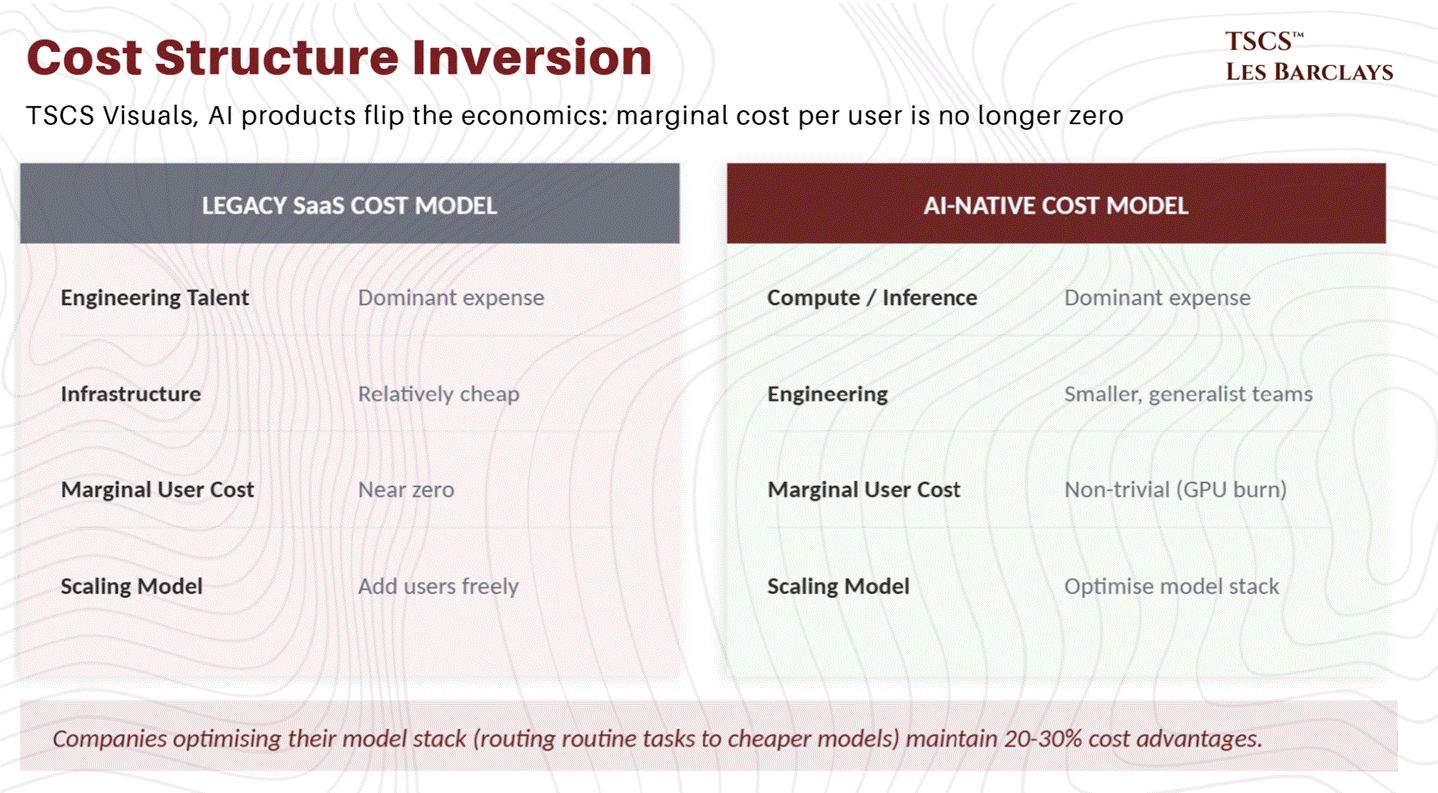

The Cost Structure Inversion

Legacy SaaS companies optimised for a cost structure where engineering talent was the dominant expense and infrastructure was cheap. AI products invert this. The marginal cost of an additional user is no longer near zero, because every interaction burns compute.

This is why routing strategies, model selection, and infrastructure efficiency determine who survives at scale. Companies that can optimise their model stack (shifting routine tasks to cheaper models, reserving frontier models for complex cases) will maintain 20-30% cost advantages over slower competitors. By the time a legacy company gets procurement approval for a multi-model strategy, AI-native competitors have already optimised three times.

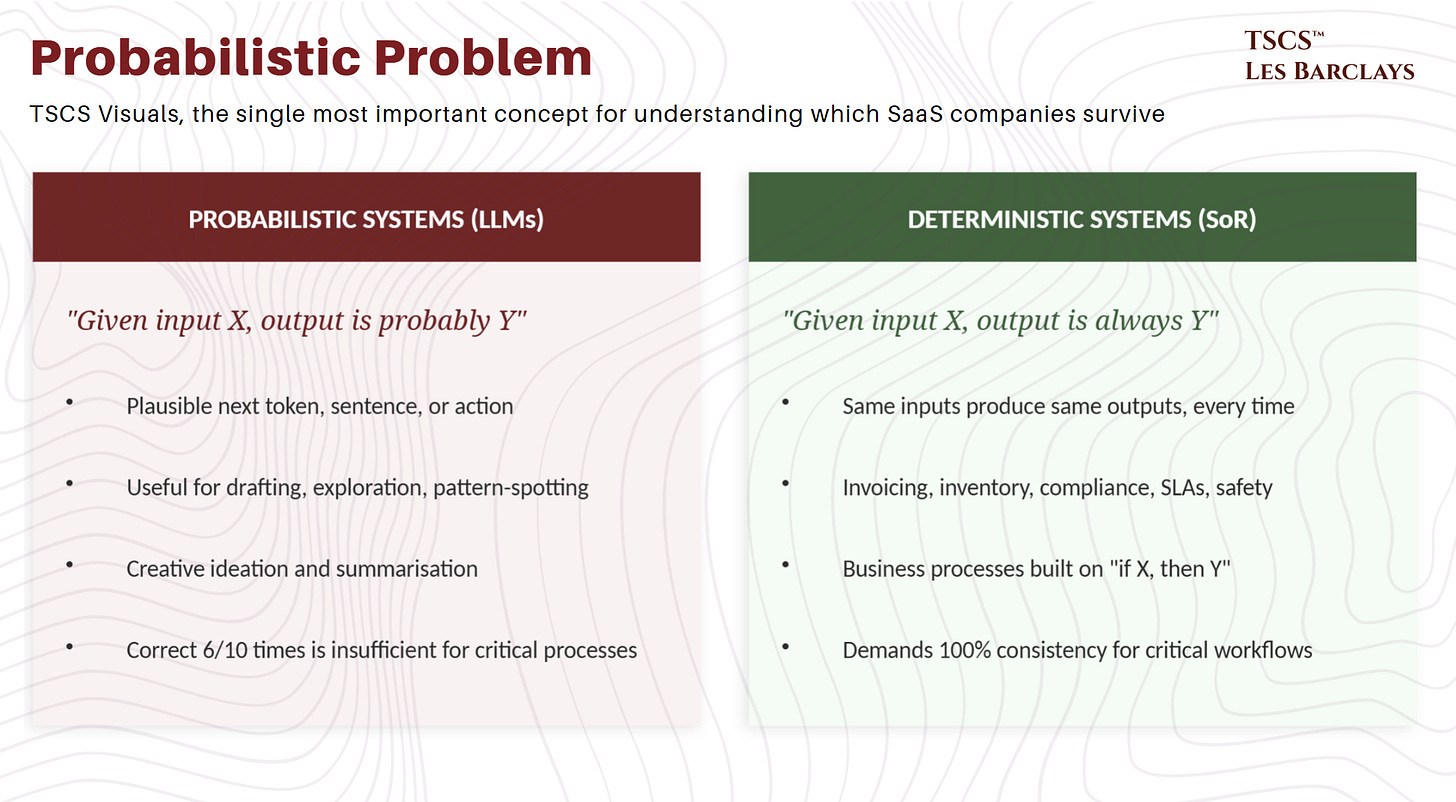

The Probabilistic Problem

All of this paints a compelling picture for AI-native companies. But there’s a critical limitation that the breathless pitch decks consistently omit, and it’s the single most important concept for understanding which SaaS companies survive and which don’t.

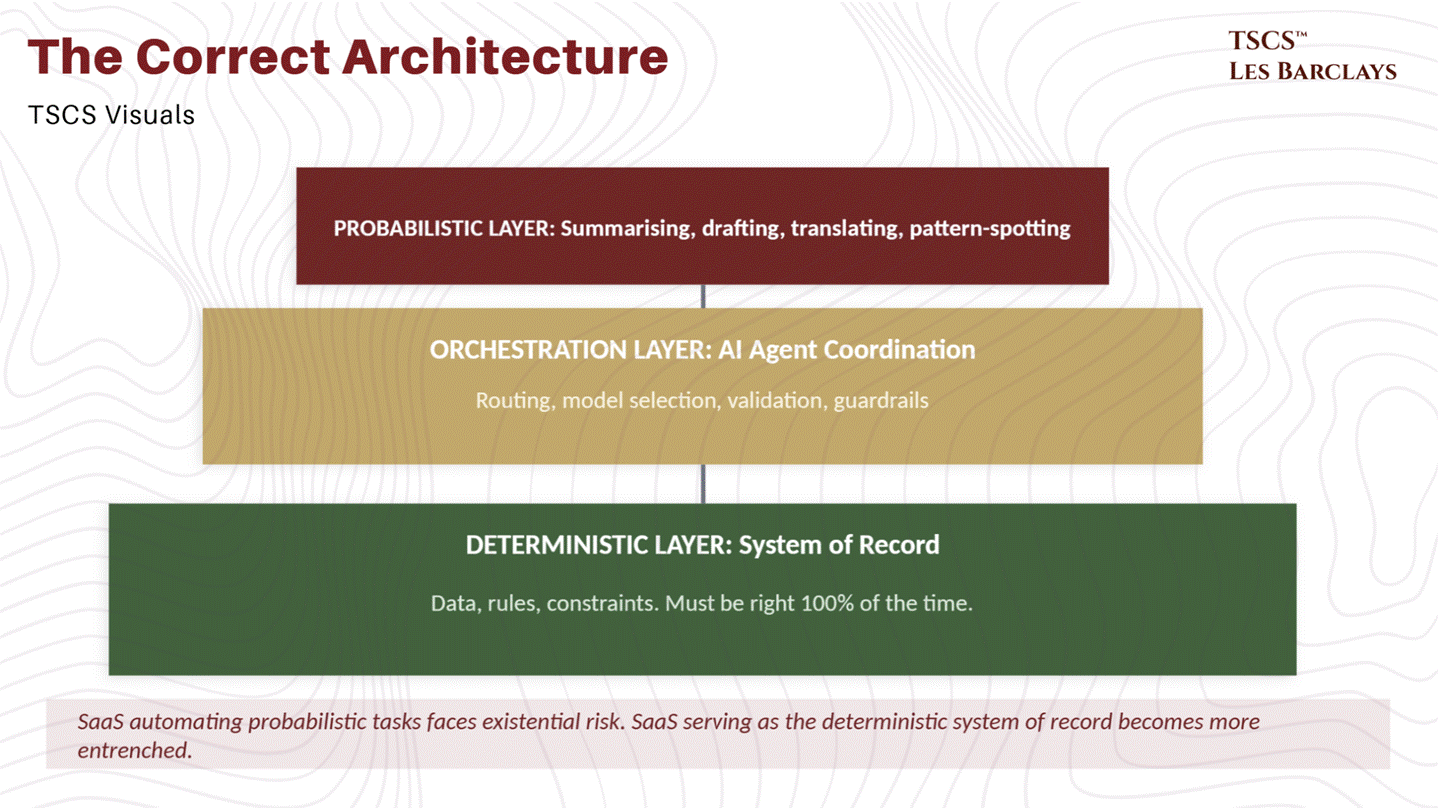

LLMs are inherently probabilistic systems. Business processes run on deterministic ones.

A probabilistic system gives you a plausible next token, next sentence, next action. It’s about likelihood; you don’t get guarantees. That’s useful for drafting, exploration, pattern-spotting, and creative ideation. A deterministic system is designed so that given the same inputs, you get the same outputs every single time. That’s how invoicing, inventory, compliance, SLAs, and safety work. Business processes are built on “if X, then Y,” not “if X, then probably Y.”

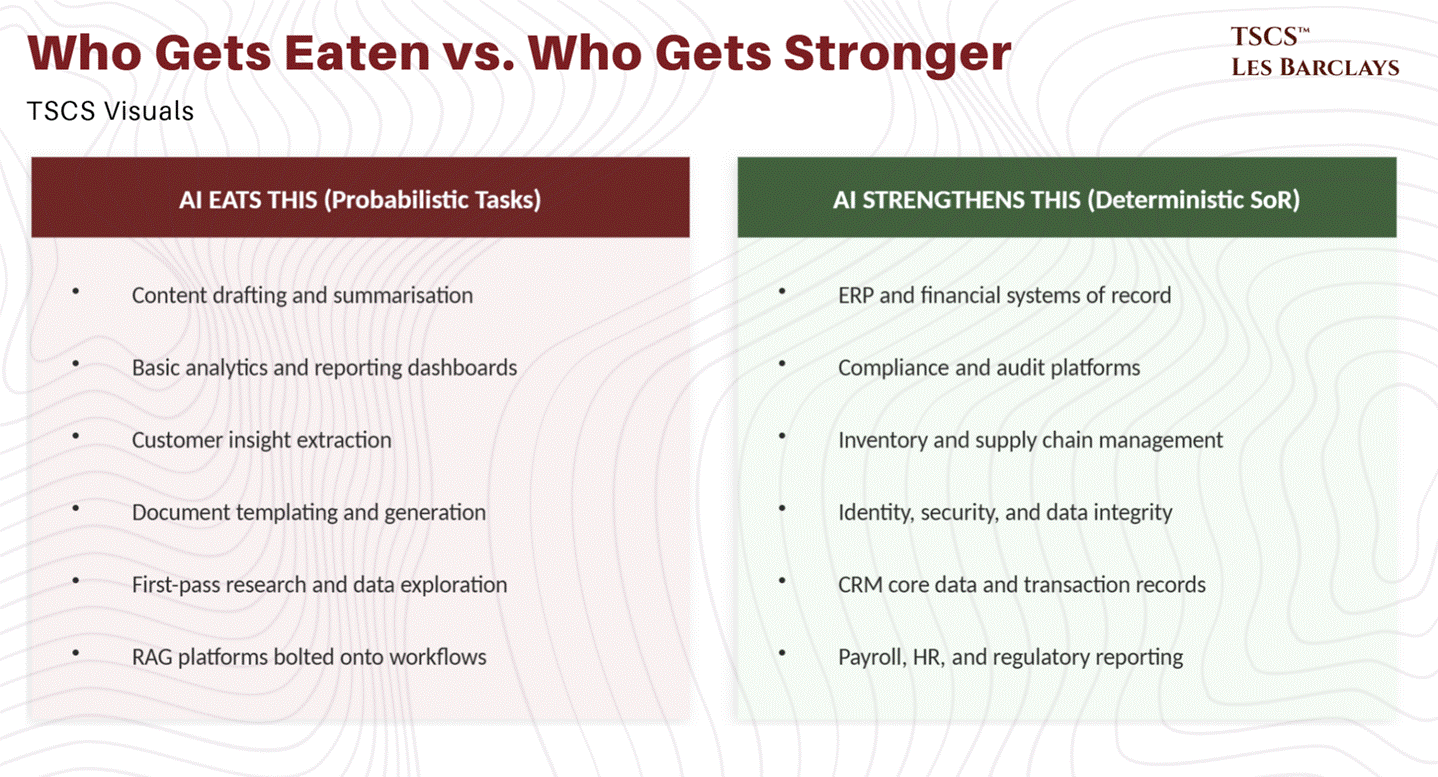

As UncoverAlpha put it in his analysis of SaaS unbundling: AI will eat the probabilistic category, while deterministic systems become more valuable by integrating AI as a complementary layer. That framing is exactly right. When enterprises deploy AI agents in 2025 and 2026, they’re not replacing their systems of record. They’re building orchestration layers on top of them. CIOs are discovering that LLMs lack the deterministic consistency required for critical industries. A system that provides the correct answer six out of ten times is insufficient when the process demands 100% consistency.

A lot of money is being incinerated on “AI agents” and “RAG platforms” that amount to the mid-2010s chatbot strategy repackaged with better branding. People are bolting probabilistic models directly into deterministic workflows and then wondering why the system hallucinates, drifts, or quietly breaks guarantees the business depends on. More agents won’t fix this. What fixes it is architectural clarity: use deterministic systems to hold your source of truth (data, rules, constraints, anything that must be right 100% of the time), and use probabilistic systems at the edges for summarising, drafting, translating, and spotting patterns that humans then validate.

This distinction between deterministic and probabilistic systems is the analytical key to everything that follows. It explains why some SaaS companies face existential risk (those automating probabilistic tasks that AI handles natively) while others become more entrenched (those serving as the deterministic system of record that AI agents need to operate through). Keep this framework in mind. We’ll apply it directly in Section 4.

Section 3: The Counter-Thesis, Why the Model Layer Is the Fragile Part

Everything I’ve laid out so far paints a dire picture for SaaS. The Claude Cowork plugins, the hiring freezes, the private credit exposure, the blanket selloff. It’s compelling.

It’s also incomplete.

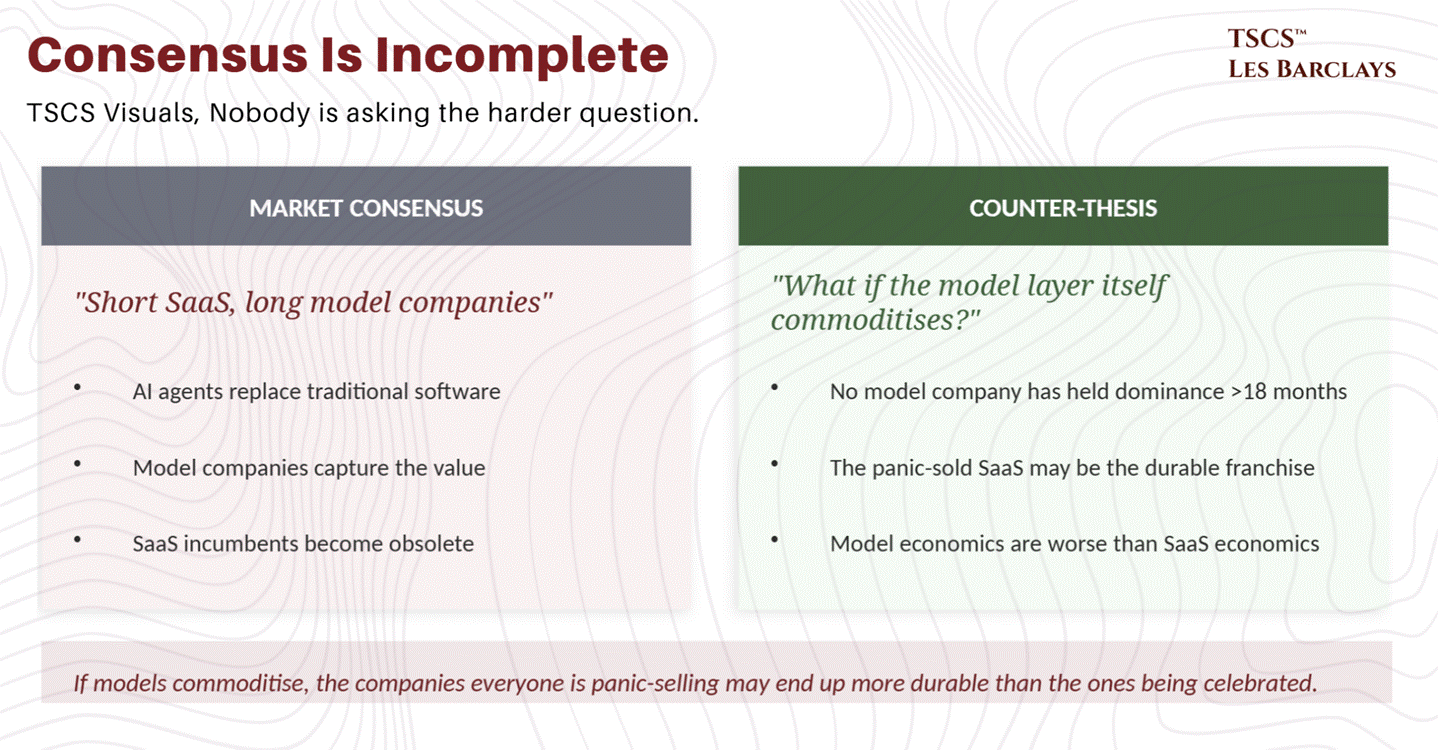

The market is treating “AI disrupts software” as a one-directional trade: short SaaS, long model companies. But nobody is asking the harder question: what happens when the model layer itself becomes a commodity?

Because that’s already happening. And if you follow the economics to their logical conclusion, the companies everyone is panic-selling may end up being more durable franchises than the ones everyone is celebrating.

The Model Layer Is Commoditising, Not Consolidating

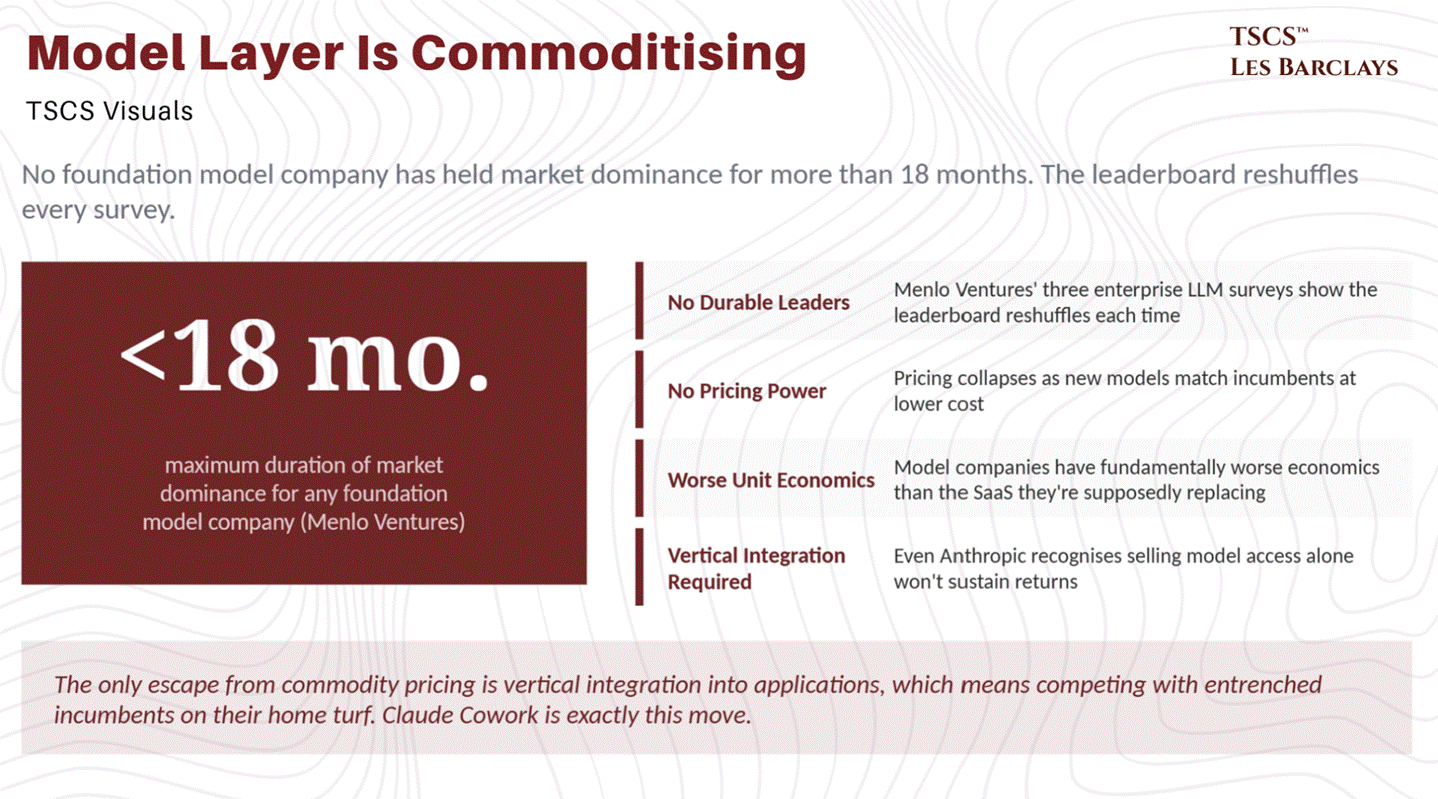

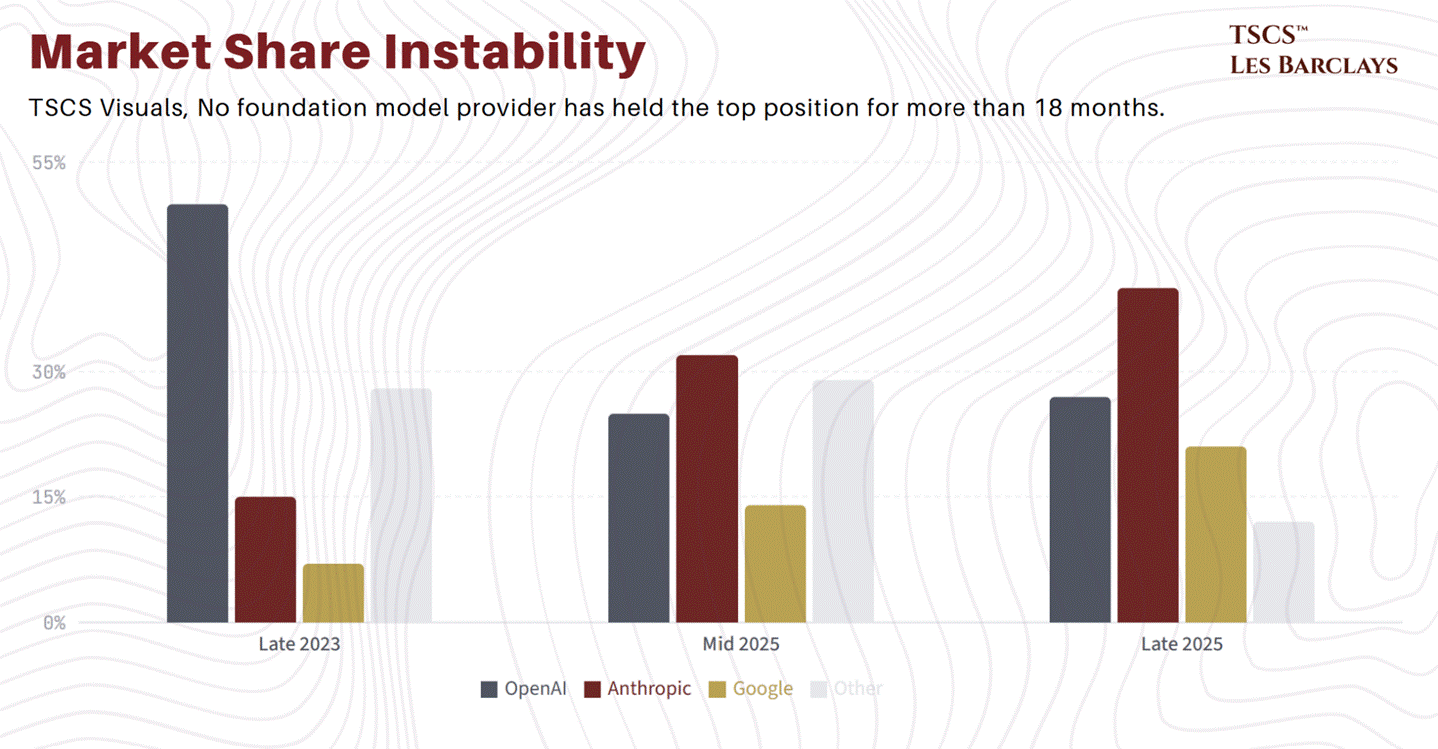

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about foundation model companies: none of them have held market dominance for more than 18 months. Not one.

Menlo Ventures has now published three enterprise LLM market surveys, and the leaderboard has reshuffled in each one (full disclosure: that includes Anthropic, the company whose product I’m typing this into). Section 4 details the exact share shifts and the full pricing trajectory, but the pattern is clear: this market has no durable leaders, no pricing power, and unit economics that are fundamentally worse than the SaaS companies the market is selling. The numbers are stark, and we lay them out in full in Section 4.

Which brings us to DeepSeek.

The DeepSeek Precedent: Why Capital Isn’t a Moat

In January 2025, a relatively obscure lab in Hangzhou released R1, a reasoning model that matched OpenAI’s o1 on key benchmarks for a reported training cost of $6 million. The real figure was almost certainly higher (estimates from SemiAnalysis suggest the full R&D and hardware investment exceeded $500 million), but even at $500 million, the point stands: DeepSeek achieved frontier-adjacent performance at a fraction of what OpenAI and Anthropic spent.

This matters enormously for anyone trying to value foundation model companies. The traditional venture capital thesis was that training frontier models requires such enormous capital (tens of billions) that only a handful of companies could compete, creating a natural oligopoly with pricing power. DeepSeek blew that thesis apart. If a Chinese lab operating under US export controls on chips can match Western frontier models at a fraction of the cost, the “capital as moat” argument is dead. As the Institute for New Economic Thinking put it, the expensive infrastructure that once served as a moat for dominant firms can be undercut.

The Mixture-of-Experts architecture, Group Relative Policy Optimisation, Multi-Head Latent Attention, these techniques are now public knowledge. The method for building a frontier-adjacent model without frontier-level capital is written, published, and being studied by every lab on earth. The logical next step is straightforward: if anyone with sufficient (but not astronomical) resources can build a competitive model, then models will be priced like commodities, and the companies building them will earn commodity returns.

The only escape from commodity pricing is vertical integration into applications, which means competing with entrenched incumbents on their home turf. Anthropic is doing exactly this with Claude Cowork, and that’s precisely why the market panicked. But think about what that move actually signals: even Anthropic, arguably the hottest AI company on earth, recognises that selling model access alone won’t generate sustainable returns. The model layer is a means to an end, not the end itself.

Application-Layer Moats Are Deeper Than They Appear

The bear case on SaaS rests on a seductive but flawed premise: that AI “systems of action” will replace “systems of record.” It sounds elegant. AI agents will just do things, and the clunky software underneath becomes irrelevant.

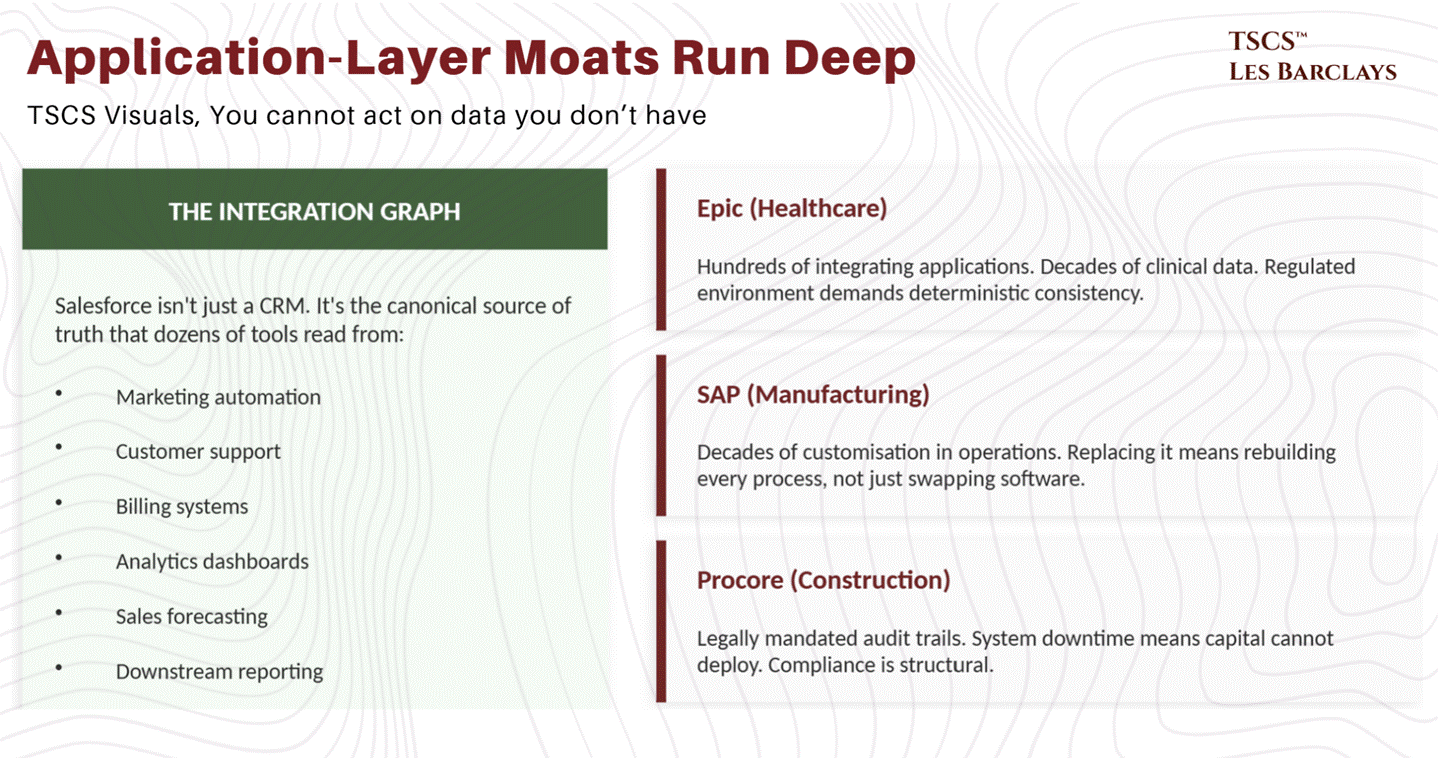

Except systems of action need systems of record underneath them. You cannot act on data you don’t have.

Salesforce isn’t just a CRM. It’s the canonical source of truth for customer data that dozens, sometimes hundreds, of other tools read from. CRM data feeds marketing automation, customer support, billing systems, analytics dashboards, and sales forecasting. Replacing Salesforce doesn’t mean swapping one application for another. It means migrating every downstream integration, retraining every workflow, rebuilding every reporting pipeline, and risking data loss across the entire stack.

This is the integration graph problem, and it’s one that the “AI replaces SaaS” narrative consistently ignores. Epic in healthcare has hundreds of integrating applications. SAP in manufacturing has decades of customisation baked into operational processes. Procore in construction has legally mandated audit trails where system downtime means capital cannot deploy. These aren’t software products. They’re institutional infrastructure. Ripping them out is a multi-year, multi-million-dollar project, and no CEO is going to bet their company on a probabilistic system to replace a deterministic one in a regulated environment.

The Compliance Moat (Measured in Years, Not Months)

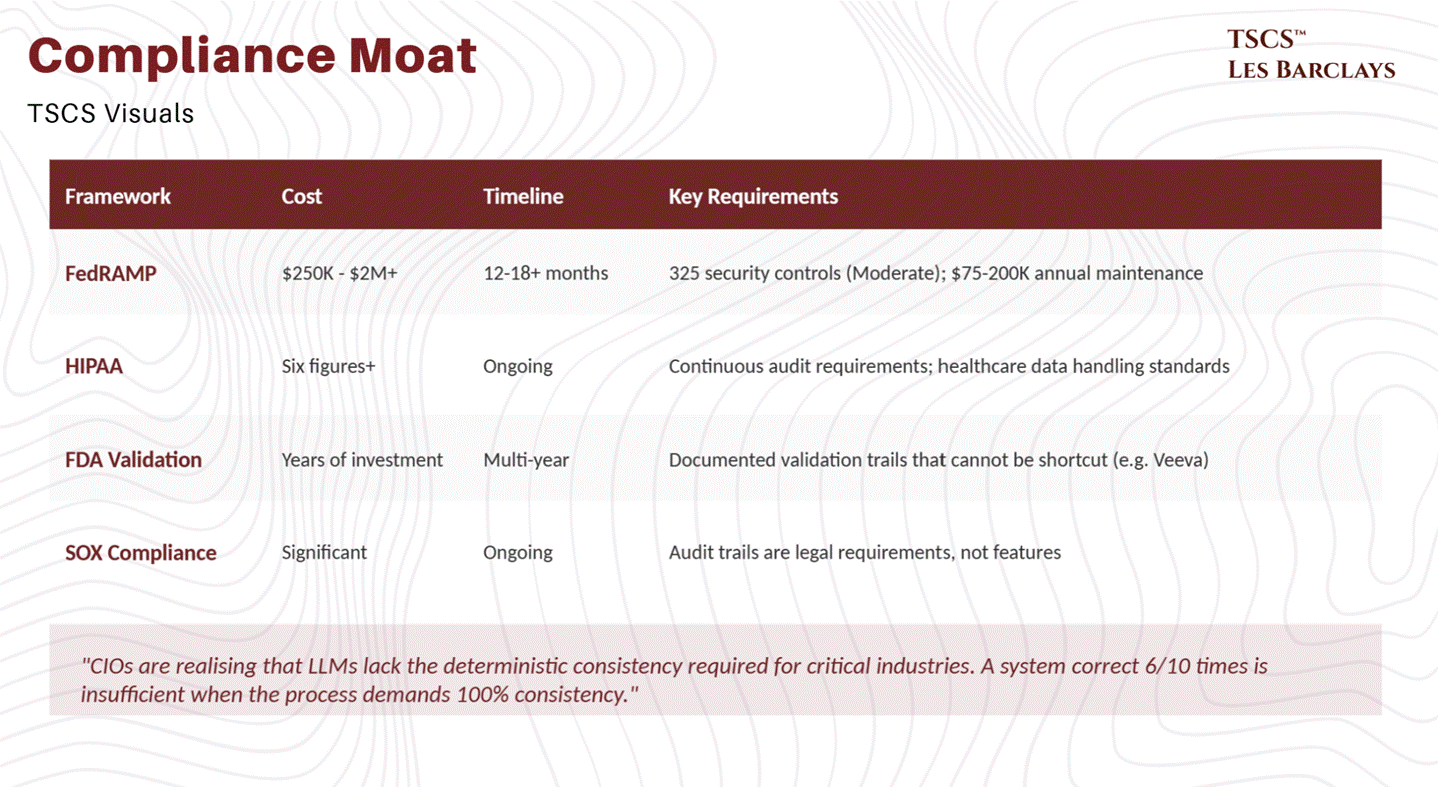

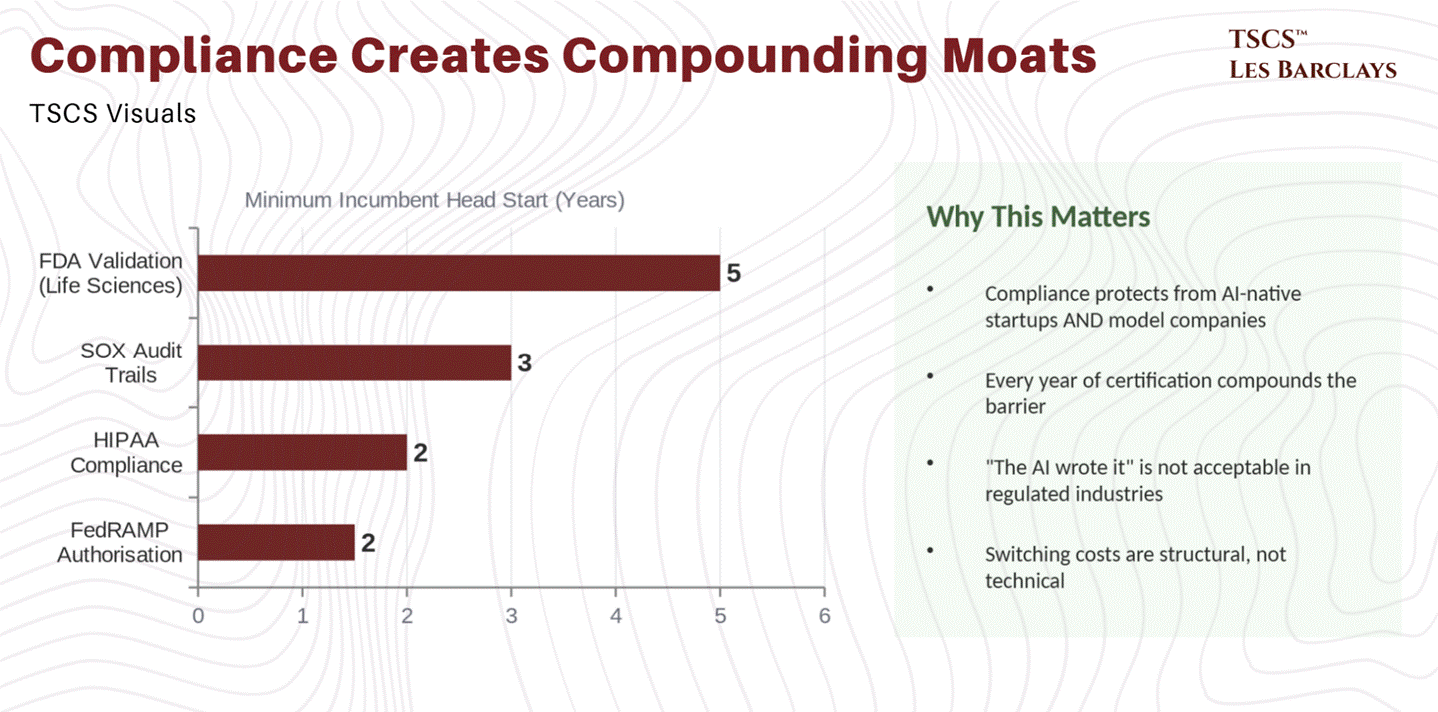

This is the part that tech Twitter consistently underestimates. Regulatory compliance isn’t a feature you bolt on. It’s a structural barrier that takes years and millions of dollars to build, and it creates switching costs that no AI agent can circumvent.

FedRAMP authorisation, the certification required to sell cloud services to US federal agencies, costs anywhere from $250,000 to over $2 million and takes 12 to 18 months or more to obtain. The Moderate level (which covers 80% of applications) requires implementation of 325 security controls. Annual maintenance adds $75,000 to $200,000 per year. And this is just one certification in one country.

HIPAA compliance for healthcare software requires minimum six-figure investments for updates, with ongoing audit requirements. FDA validation for life sciences software (think Veeva) involves years of documented validation trails that cannot be shortcut. SOX compliance for financial software means audit trails are legal requirements, not features. “The AI wrote it” is not an acceptable answer in any regulated industry. As the deterministic/probabilistic framework from Section 2 makes clear, a system that provides the correct answer six out of ten times is insufficient when the process demands 100% consistency.

These compliance frameworks don’t just protect incumbents from AI-native startups. They create a compounding advantage. Every year that Veeva has been FDA-validated is another year of audit trail that a new entrant would need to replicate. Every FedRAMP-authorised product has 12-18 months of head start that an AI-native competitor hasn’t even begun.

The Demo-to-Deployment Gap Is Enormous

This is perhaps the most underappreciated dynamic in the entire AI-versus-SaaS debate. Demos are not deployments. And the gap between the two is vast.

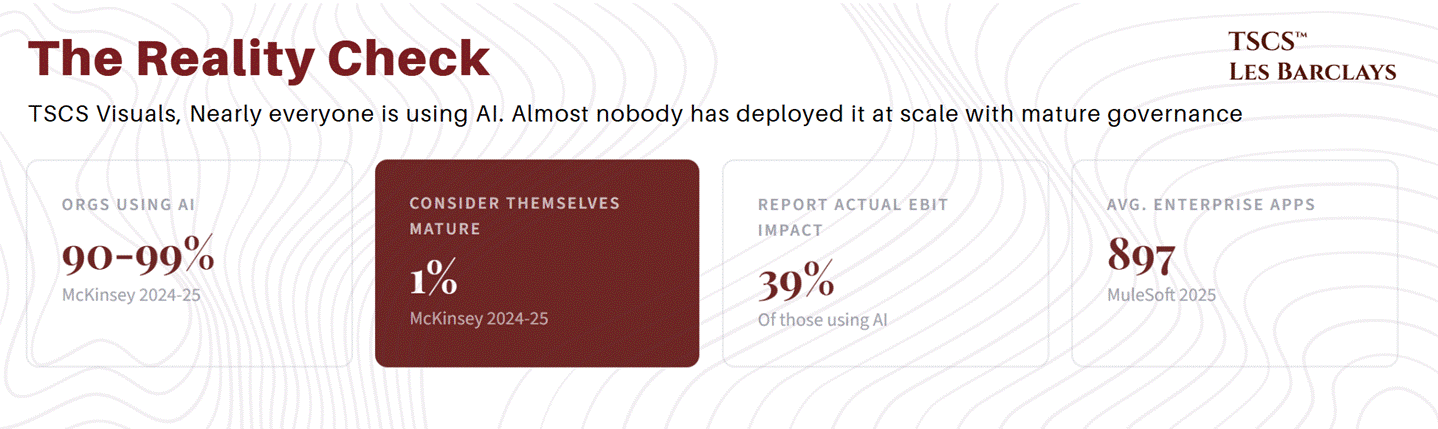

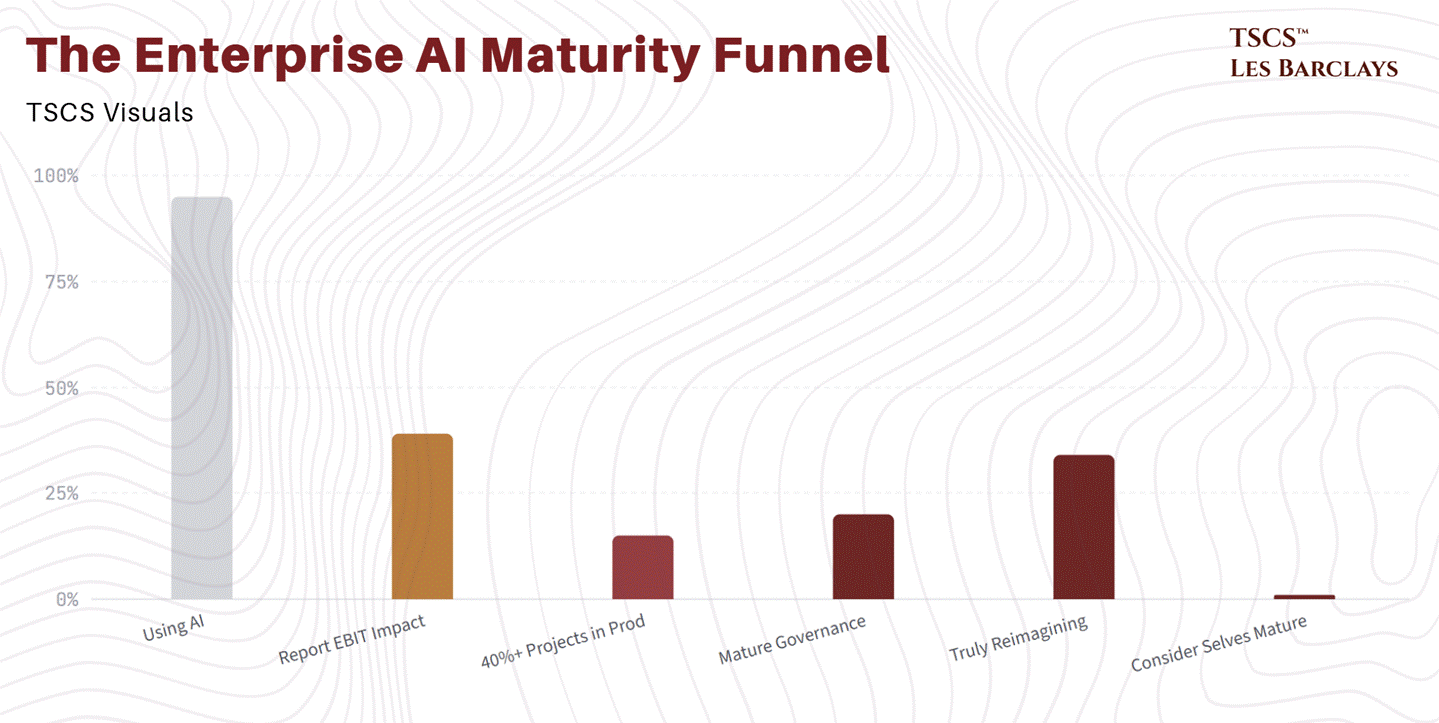

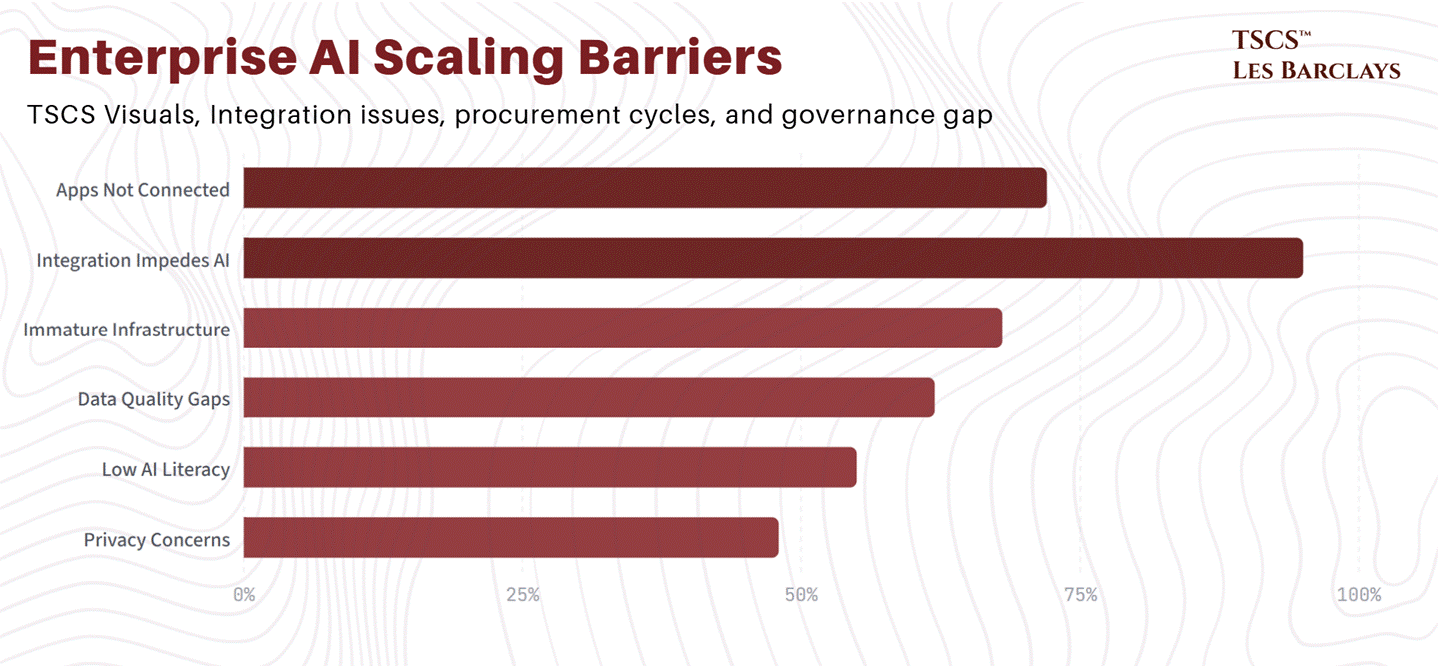

McKinsey’s 2024-25 surveys found that nearly 90-99% of organisations are using AI, yet only 1% consider themselves “mature,” and roughly 39% report actual EBIT impact. MuleSoft’s 2025 Connectivity Benchmark Report reveals that only 28% of enterprise applications are actually connected, and 95% of IT leaders say integration issues impede AI adoption. Organisations average around 897 applications. Capgemini lists the top scaling barriers as immature infrastructure, data quality gaps, low AI literacy, and privacy concerns.

Gartner predicts that by 2026, 40% of enterprise applications will include task-specific AI agents, up from less than 5% today. That projection sounds bullish until you realise it means 60% won’t. And “including” an AI agent is not the same as “replacing existing software with” an AI agent. The most common pattern isn’t replacement, it’s augmentation: embedding AI into existing workflows to make them faster, not tearing out the workflow entirely.

Deloitte’s 2026 State of AI report paints a more nuanced picture than the headlines suggest. Worker access to AI rose by 50% in 2025, and the number of companies with 40%+ of projects in production is set to double in six months. But only one in five companies has a mature model for governance of autonomous AI agents. And only 34% are “truly reimagining the business.” The rest are bolting AI onto existing processes, which is exactly what benefits incumbents.

The “AI can do X” demo is not the same as “enterprises will deploy X at scale with appropriate governance, security, and compliance.”

Anyone who has worked inside a large organisation knows this intuitively.

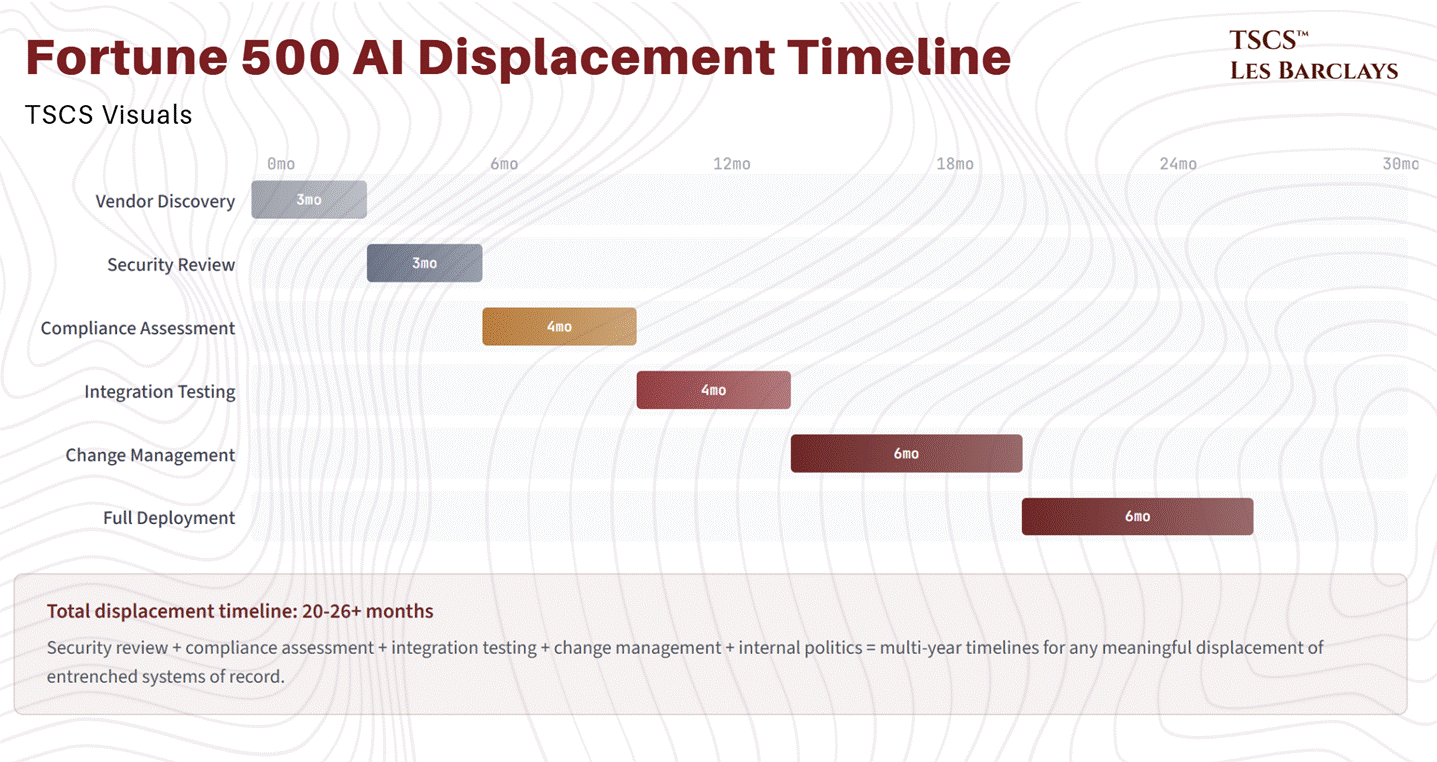

The procurement cycle alone for a Fortune 500 company is 6-18 months. Multiply that by the security review, the compliance assessment, the integration testing, the change management, and the internal politics, and you’re looking at multi-year timelines for any meaningful displacement of an entrenched system of record.

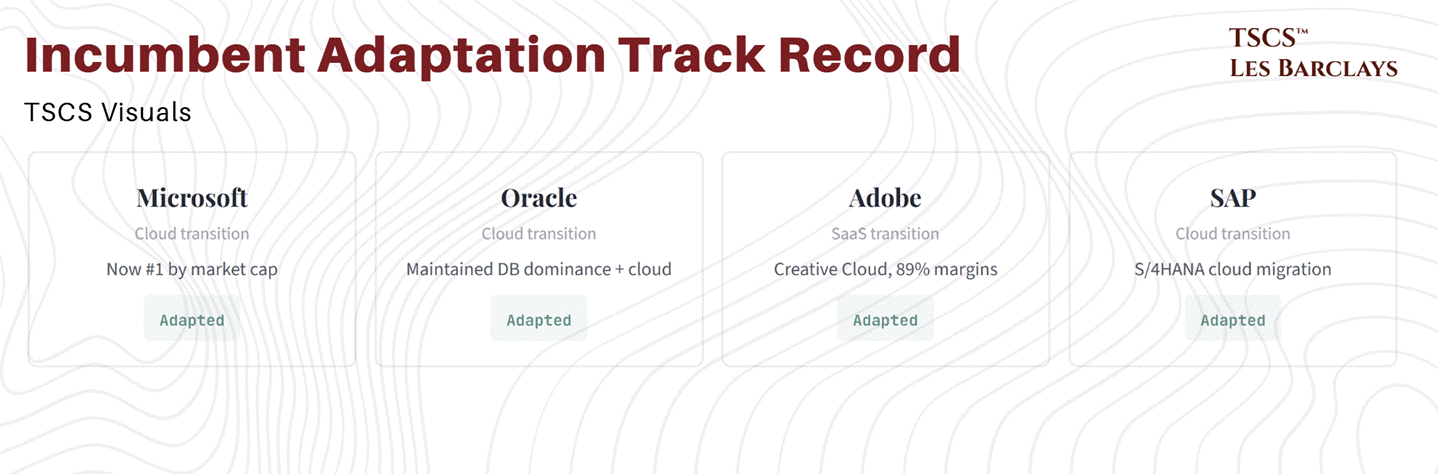

Historical Precedent Favours Adaptation, Not Extinction

We’ve been here before. The cloud transition was supposed to kill on-premise software. Oracle was dead. SAP was dead. Microsoft was a dinosaur. Instead, Microsoft successfully pivoted to Azure and Office 365 and is now the most valuable company on earth. Oracle maintained enterprise database dominance while adding cloud revenue. The incumbents didn’t die. They adapted. And they captured most of the value.

McKinsey’s research on technology transitions found that legacy vendors closest to the customer, with high industry and domain expertise, consistently protected their market share across disruption cycles. The same dynamic is already playing out here. The ICONIQ data from Section 1 confirms it: 70% of AI builders are focused on vertical applications, not foundation models. They’re building on top of models, not competing with them. The model layer is commoditising, and the value is shifting up the stack to whoever owns the data and workflows.

That’s the SaaS incumbents everyone is selling.

The Question the Market Should Be Asking

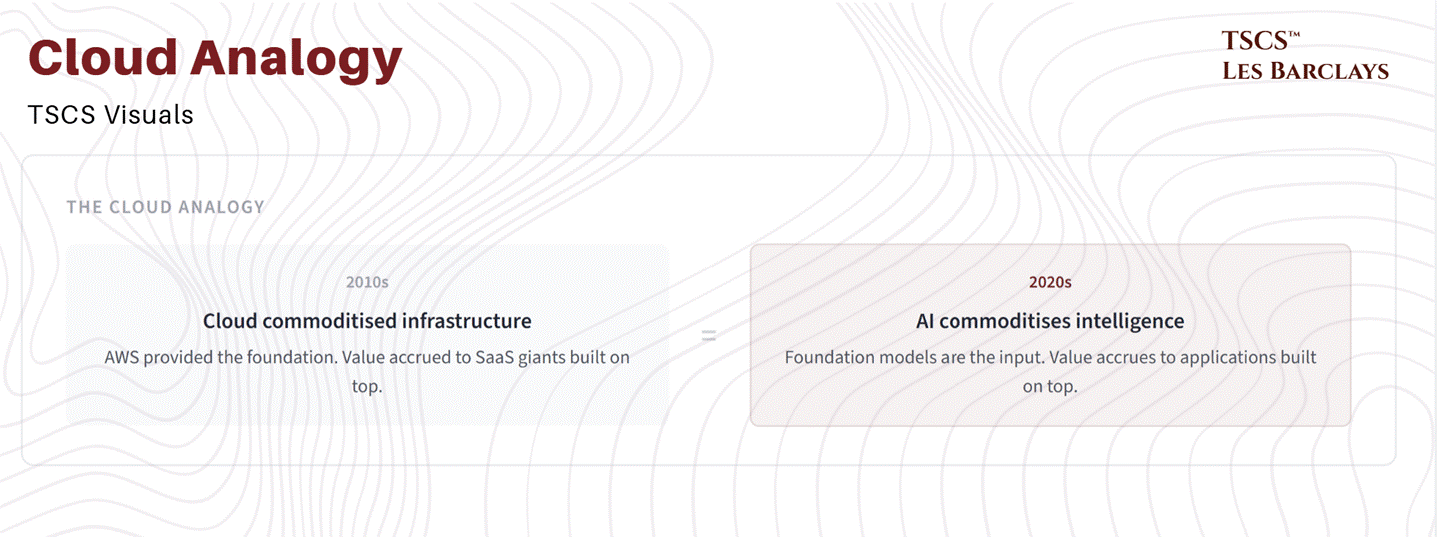

The market is treating this as a binary: AI wins, SaaS loses. But the actual question is far more nuanced. It’s not “will AI disrupt software?” Of course it will. The question is: “where does the value accrue when the model layer is free?”

When cloud computing commoditised infrastructure, the value didn’t accrue to AWS’s competitors or to the cloud infrastructure itself. It accrued to the applications built on top of that infrastructure. Salesforce, ServiceNow, Workday, the entire SaaS ecosystem was built on cheap, commoditised cloud compute.

Foundation Capital made this exact analogy in their post-DeepSeek analysis: “As the cost of intelligence plummets, AI is evolving from static tools to dynamic systems of agents that reason, plan, and act. This follows a familiar pattern: when core technologies commoditise, value moves up the stack. We saw this with cloud computing, AWS provided the foundation, but the real winners were the SaaS giants that built on top.”

The same AI model commoditisation that’s terrifying the SaaS market is actually the best possible outcome for SaaS incumbents. Cheaper AI means cheaper for SaaS companies to embed intelligence into their own products. It means Veeva can add AI-powered clinical trial analysis without building its own model. It means ServiceNow can deploy AI-driven workflow automation using whichever model offers the best price-performance ratio that quarter. It means the moat isn’t the AI, it’s the data, the workflows, the integrations, and the regulatory certifications that took decades to build.

The model layer is the commodity input. The application layer is where the margin lives.

Section 4: The Model Layer Economics Deep Dive

Section 3 made the qualitative case that the model layer is commoditising. This section puts numbers behind that claim. If the economics of foundation model companies are genuinely worse than the SaaS companies the market is selling to buy them, then the entire “AI kills SaaS” narrative doesn’t just weaken. It inverts.

4A: The Unit Economics Comparison

The divergence between SaaS incumbents and foundation model companies isn’t subtle.

Fortress Zone SaaS companies operate with gross margins that private equity investors would describe as “beautiful”: CrowdStrike at 81%, Adobe at 89%, ServiceNow at 78%, Veeva at 75%. The marginal cost of serving an additional customer on an existing software platform is close to zero. The server is already running. The code is already written. Every incremental dollar of revenue falls almost entirely to the bottom line.

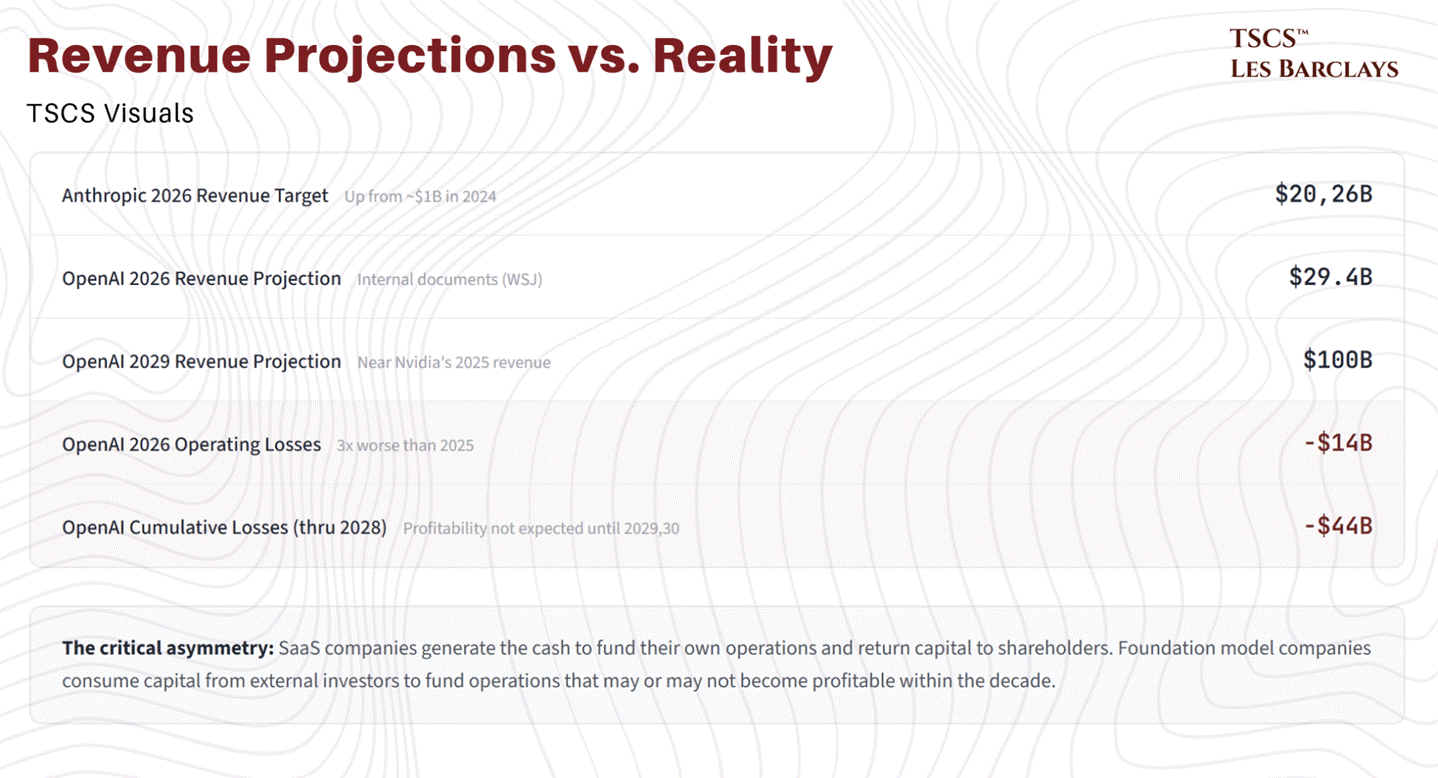

Foundation model companies occupy a different universe. Anthropic’s gross margins in 2024 were negative 94% to negative 109%, depending on whether you include free-tier users. For every dollar of revenue, Anthropic spent nearly two dollars just on inference infrastructure, before counting R&D, talent, or anything else. The company projected improvement to roughly 50% gross margins in 2025, then revised that figure down to 40% after inference costs on Google Cloud and AWS came in 23% higher than anticipated. Even that revised 40% figure would put Anthropic’s margins below every single SaaS company in our Fortress Zone taxonomy.

OpenAI’s picture is, if anything, worse. The company’s “compute margin” reportedly improved from 35% in early 2024 to roughly 70% by October 2025. That sounds encouraging until you realise what it excludes.

OpenAI spent $6.7 billion on R&D in the first half of 2025 alone, $2 billion on sales and marketing in the same period, and stock-based compensation is running at $6 billion annually. When you include all costs, OpenAI spent approximately $1.69 for every dollar of revenue it generated in 2025. The company projects $14 billion in operating losses for 2026, roughly three times worse than 2025. Internal documents obtained by the Wall Street Journal show cumulative losses of $44 billion through 2028, with profitability not expected until 2029 or 2030.

For perspective: the cumulative cash burn OpenAI projects through 2029 ($115 billion) exceeds the inflation-adjusted cost of the Apollo programme.

Here is the comparison in full:

On every metric that matters for long-term business quality, SaaS incumbents score higher. The market is selling 80% gross margin businesses to buy 40% gross margin businesses. It is selling businesses with 124% NRR to buy businesses whose per-unit pricing is collapsing annually. It is selling businesses that generate billions in free cash flow to buy businesses that consume billions in venture capital.

Something doesn’t add up.

4B: The API Pricing Freefall

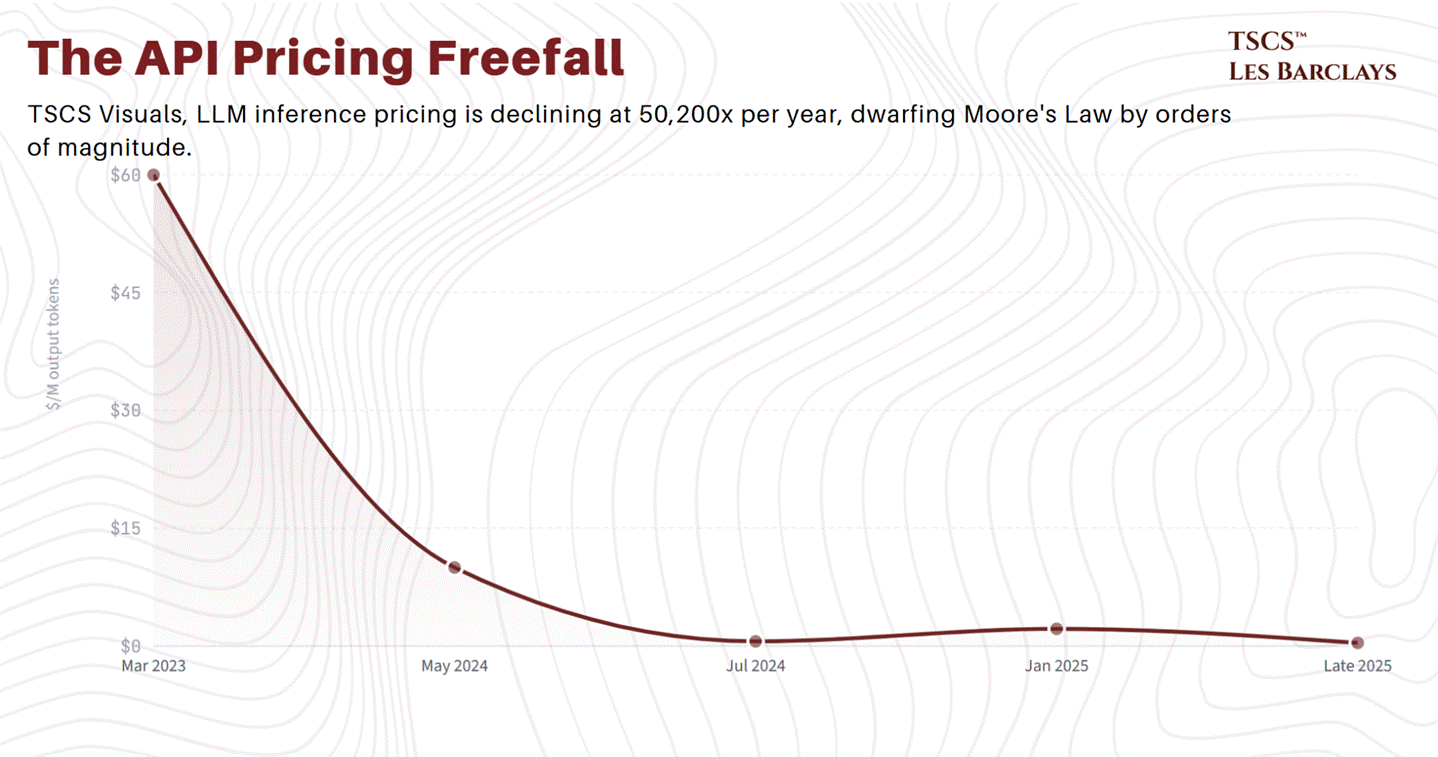

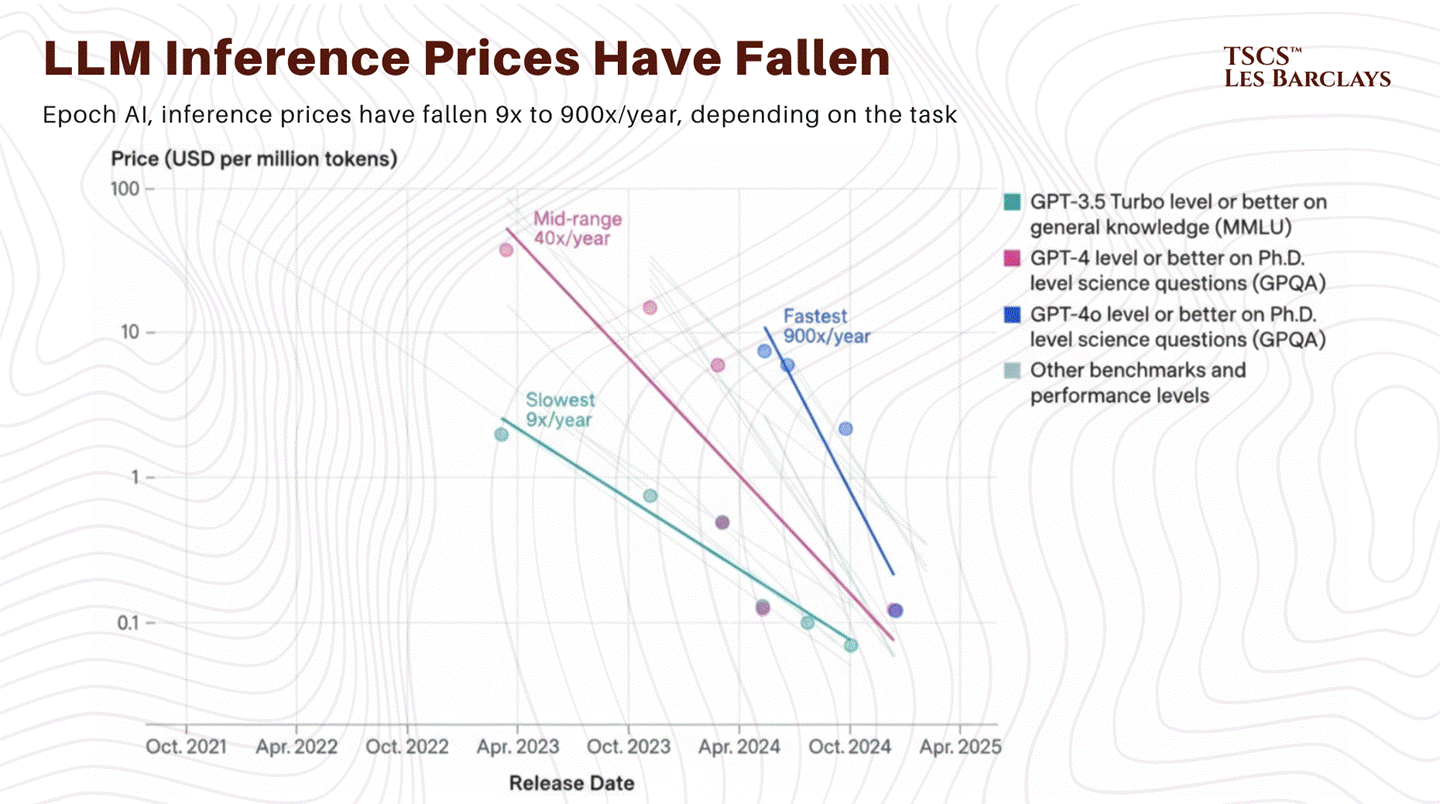

The pricing data deserves its own treatment because the magnitude of the decline is genuinely unprecedented in technology markets.

When OpenAI launched GPT-4 in March 2023, the flagship API was priced at $30 per million input tokens and $60 per million output tokens. That was the cost of frontier intelligence. Within 16 months, GPT-4o had brought output pricing down to $10 per million tokens, an 83% decline. By mid-2024, GPT-4o Mini arrived at $0.15 input and $0.60 output, a 99% reduction from original GPT-4 pricing for comparable task performance. As of late 2025, GPT-4-equivalent performance costs roughly $0.40 per million tokens, down from $20 just three years earlier.

Anthropic’s pricing trajectory follows the same curve. Claude 3 Opus launched at $15/$75 per million tokens (input/output). Claude 4.6 Opus launched at $5 per million tokens, a 67% reduction in a single generation.

Then DeepSeek entered the picture. DeepSeek R1 debuted at $0.55/$2.19 per million tokens, undercutting Western frontier models by roughly 90%. DeepSeek V3.2 offers reasoning capabilities competitive with GPT-5 at approximately one-tenth the price. By February 2026, OpenAI and Google have repeatedly slashed API costs to match what the market now calls the “DeepSeek Standard.” The price ceiling is set, and every lab must now match it or justify a premium against it.

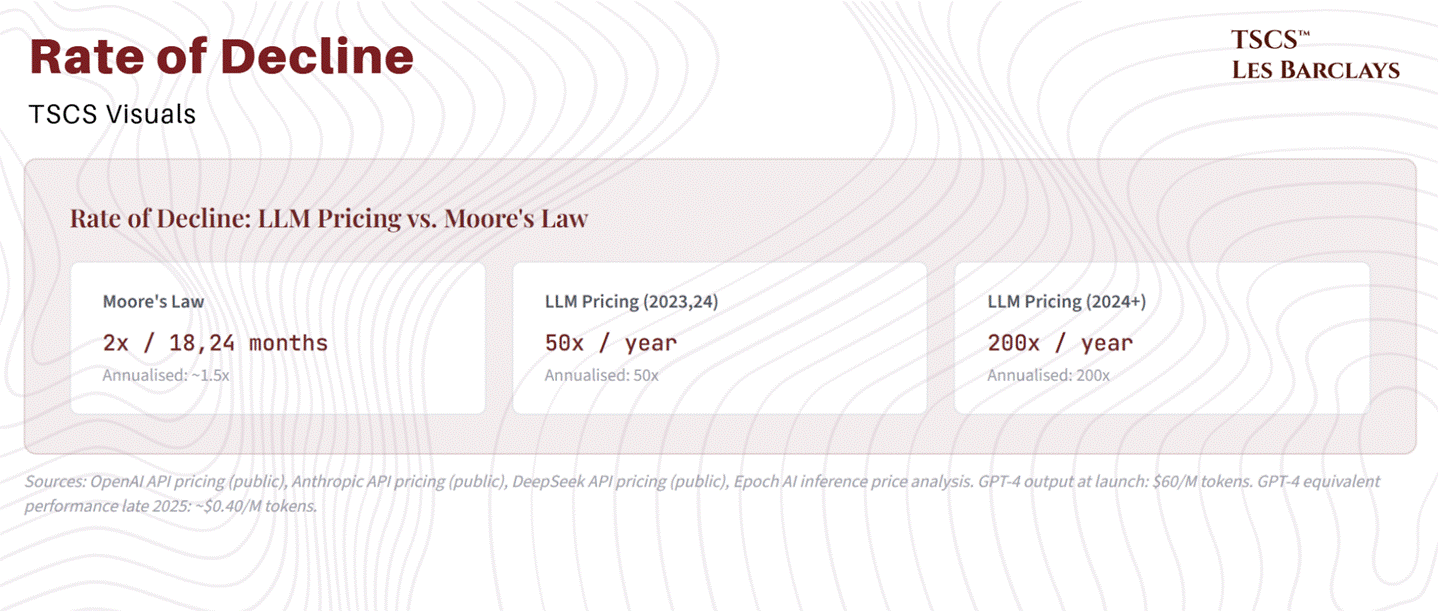

Epoch AI’s analysis of inference price trends found that the rate of decline has actually accelerated. For models at GPT-4-equivalent performance levels, the median price decline was 50x per year through early 2024. From January 2024 onwards, that accelerated to 200x per year. Models that were state-of-the-art in 2023 have experienced approximately 1,000x price declines at equivalent intelligence levels.

For context, the semiconductor industry’s famed Moore’s Law delivered roughly a 2x improvement in price-performance every 18-24 months. LLM inference pricing is declining at 50-200x per year. This is not a gradual commoditisation. It is a pricing collapse without precedent in the history of technology markets.

4C: The Capital Requirements Arms Race

The bull case for foundation model companies requires believing one of two things: either margins will improve dramatically as scale increases, or revenue growth will be so explosive that margins become temporarily irrelevant. Both assumptions deserve scrutiny.

On margins, Anthropic projects reaching 77% gross margins by 2028. That would bring it into SaaS territory. But this projection was made before the company revised its 2025 margin forecast down by 10 percentage points, and before inference costs exceeded expectations by 23%. The path from 40% to 77% requires algorithmic efficiency gains, hardware cost declines, and revenue mix shifts toward higher-margin enterprise contracts that all need to go right simultaneously. It’s plausible. It’s not guaranteed. And even if Anthropic achieves 77% by 2028, it will have burned through billions in capital to get there, capital that SaaS companies never needed.

On revenue, the projections are staggering. Anthropic targets $20-26 billion in 2026 revenue, up from roughly $1 billion in 2024. OpenAI’s internal documents project $29.4 billion in 2026 revenue, scaling to $100 billion by 2029. To contextualise the latter figure: Nvidia generated approximately $130 billion in 2025 revenue on the back of what amounts to a near-monopoly over the largest hardware boom in technology history. OpenAI expects to approach that level in four years from a standing start.

These are not implausible figures if current adoption trends continue. Enterprise LLM spend has already tripled from roughly $13 billion in late 2024 to $37 billion in 2025, according to Menlo Ventures’ year-end survey. The market is growing fast enough to support massive revenue numbers. The question is whether the revenue belongs durably to any single provider.

Training frontier models costs hundreds of millions per run, and the trend line from Epoch AI shows training costs growing at 2.4x per year. By 2027, the largest training runs are expected to cost over $1 billion. Dario Amodei stated that “close to a billion dollars” was already being spent on single training runs in 2024.

Anthropic has raised over $13 billion, recently seeking an additional $10 billion at a $350 billion valuation. OpenAI has raised approximately $64 billion in total primary funding. Google DeepMind is backed by Alphabet’s balance sheet but cannibalises cloud margins in the process. Meta open-sources its models as a loss leader to drive engagement across its core platforms. OpenAI has committed $250 billion to Azure cloud services and signed a $38 billion AWS deal, the largest cloud contracts ever executed.

But hear me out: SaaS companies generate the cash to fund their own operations and return capital to shareholders. Foundation model companies consume capital from external investors to fund operations that may or may not become profitable within the decade. In an environment where interest rates remain elevated and the cost of capital is not zero, that distinction matters enormously.

The risk is not that these companies fail to grow. They are clearly growing at extraordinary rates. The risk is that they grow into a market structure where the model layer earns commodity returns while consuming capital at unprecedented rates. That is not a SaaS business. It is an infrastructure business with infrastructure economics, and the market is valuing it like a software business with software margins.

4D: The Market Share Instability Problem

The final piece of the model layer economics puzzle, and arguably the most underappreciated, is the complete absence of durable market position.

In late 2023, OpenAI held 50% of enterprise LLM API usage. By mid-2025, that had collapsed to 25%, with Anthropic surging to 32%. By year-end 2025, Anthropic had extended to 40%, OpenAI had slipped further to 27%, and Google had climbed to 21% (tripling from 7% in 2023). No provider has held the top position for more than 18 months.

Compare that to enterprise software. AWS launched in 2006 and still holds roughly 31% of global cloud IaaS market share nearly two decades later. Salesforce has been the CRM market leader for over 15 years. Oracle has maintained enterprise database dominance for three decades. Microsoft Office has been the productivity standard for 30+ years. That is what durable market position looks like.

In the model layer, the leaderboard is not just moving. It is spinning. And this instability is not a temporary phenomenon that will settle into oligopoly. It is a structural feature of a market where the underlying product is converging toward commodity status.

As Deedy Das at Menlo Ventures noted, “even when switching costs are low, most just upgrade to the latest model from their preferred provider.” That observation is revealing precisely because of what it implies: the stickiness, such as it is, comes from inertia and convenience, not from data lock-in or integration depth. The moment a competitor releases a model that is meaningfully better or cheaper, the switching cost is changing an API endpoint. That is a fundamentally different competitive dynamic than the one facing a Fortune 500 that has embedded its operations in Salesforce or ServiceNow over a decade.

You cannot build a durable valuation on volatile market share in a commodity market with collapsing unit pricing. The question “who will win the model layer?” may be the wrong question entirely. The better question is: “will anyone earn excess returns in the model layer?” And the data, at this point, suggests the answer is “probably not for long.”

The Synthesis

Would you rather own the business that generates $10 billion in free cash flow with 80% gross margins and 20 years of embedded customer relationships? Or the business that projects 40% gross margins on a good quarter, has raised $13 billion in venture capital to stay alive, and could lose half its market share in the time it takes to release a new model?

The market has given its answer. I think the market is wrong. The model layer is the commodity input. The application layer is where the margin lives. And at current valuations, you’re being paid to take the right side of that trade.

Section 5: The Taxonomy of Vulnerability

Section 5: The Taxonomy of Vulnerability

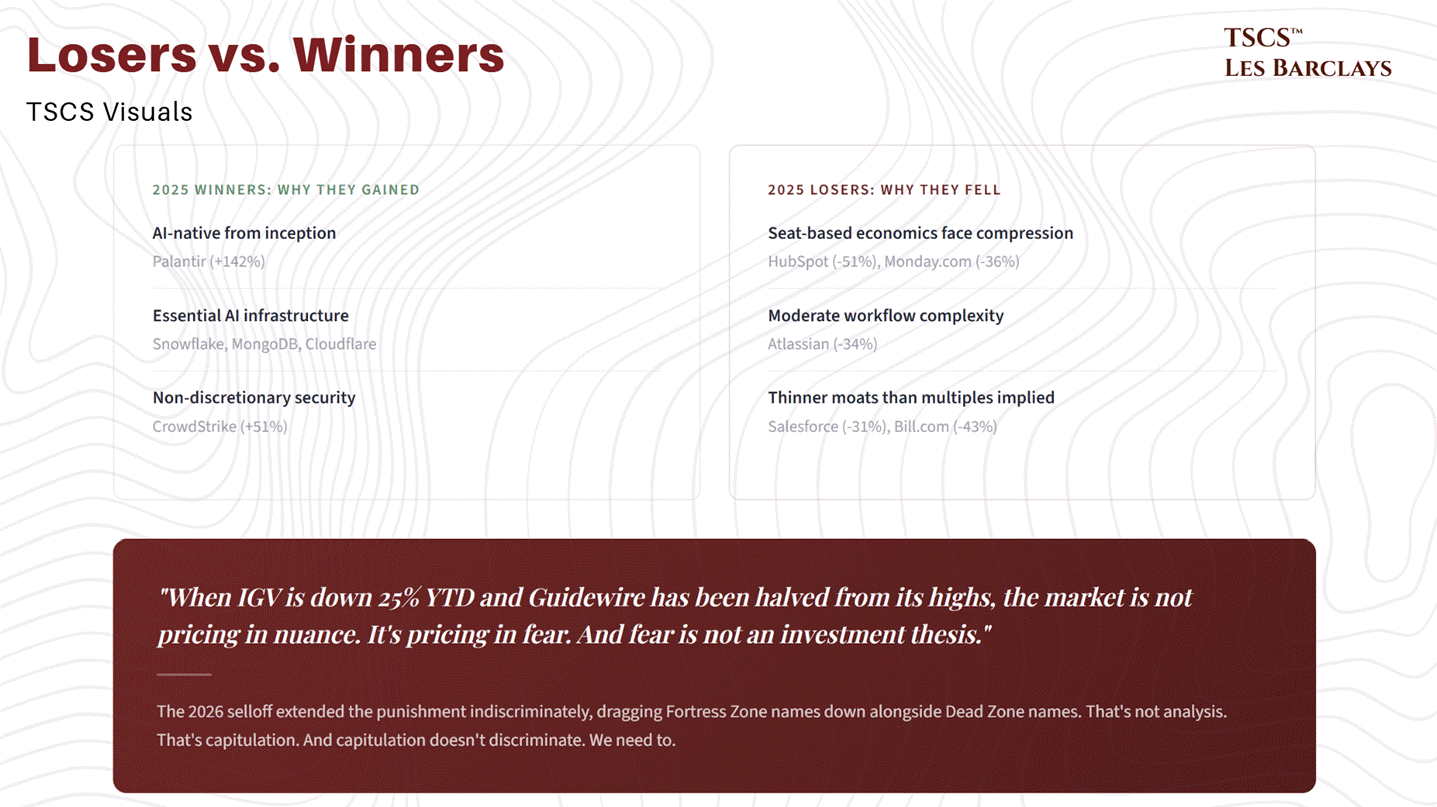

So the model layer is commoditising, the application layer has deeper moats than the market appreciates, and the selloff is indiscriminate. We’ve established all of that. But saying “the market is wrong” is useless without a framework for identifying exactly where it’s wrong, and who benefits or bleeds from here.

Not all SaaS is created equal. The market is treating the sector like a monolith, which is precisely why the opportunity exists. When Jefferies traders report “get me out” selling they haven’t seen since 2008, that’s not analysis. That’s capitulation. And capitulation doesn’t discriminate.

We need to.

The Framework

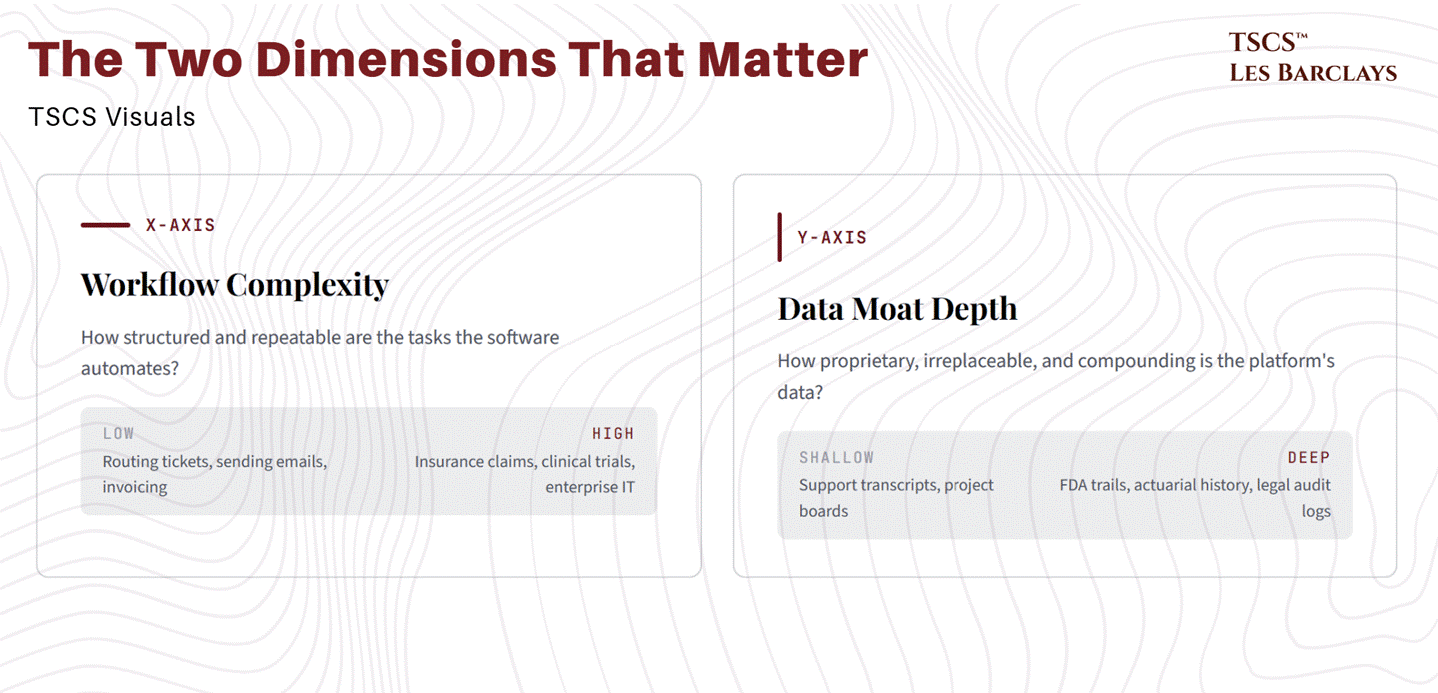

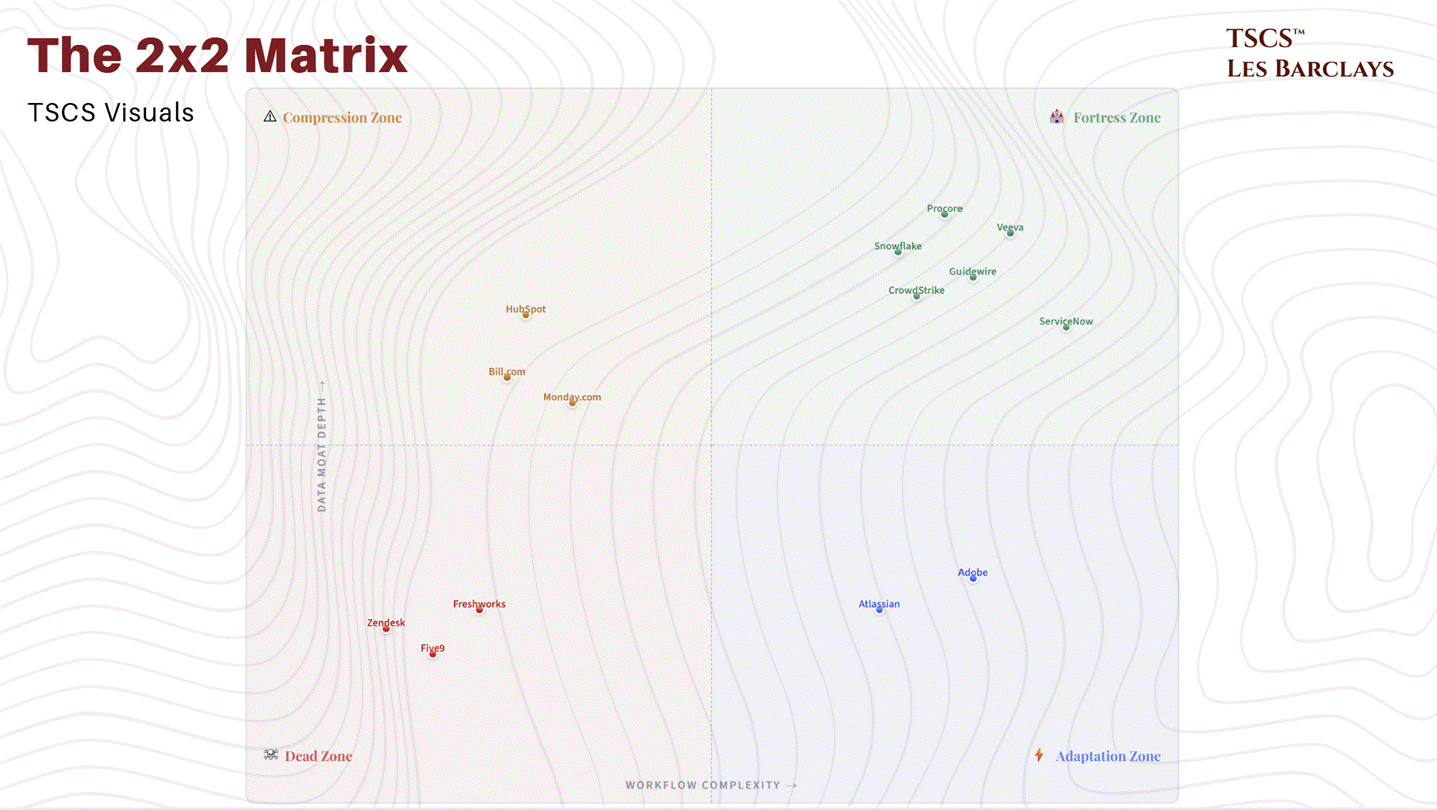

I’ve built a simple 2x2 matrix that maps every SaaS company along two axes:

X-axis: Workflow complexity. How structured and repeatable are the tasks the software automates? On the left end, you have simple, templated processes (routing a support ticket, sending a marketing email, generating an invoice). On the right, you have judgment-intensive, multi-stakeholder workflows that involve regulatory nuance, institutional knowledge, and deeply nested decision trees (adjudicating an insurance claim, managing a clinical trial, orchestrating enterprise IT across 500 applications).

Y-axis: Data moat depth. How proprietary, irreplaceable, and compounding is the data the platform accumulates? At the bottom, data is shallow, replicable, and easily exported (customer support transcripts, basic CRM records, project boards). At the top, data is deeply institutional, regulatory in nature, and functionally impossible to recreate (FDA validation trails, insurance actuarial histories, construction audit logs that are legal requirements).

The intersection of these two dimensions determines whether AI is an existential threat, a temporary headwind, or an outright tailwind for a given company.

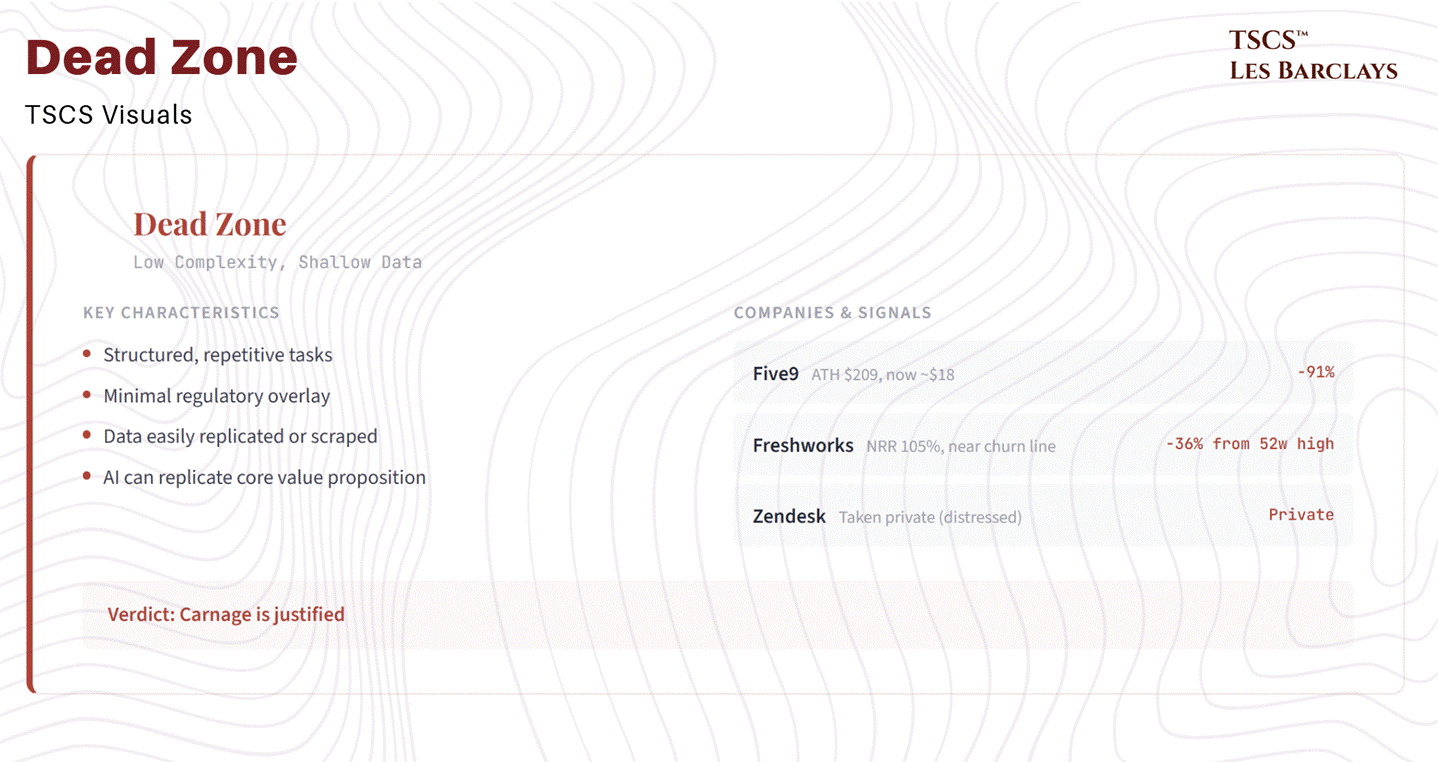

Quadrant 1: The Dead Zone (Low Complexity, Shallow Data)

This is where the carnage is real and justified. These companies automate structured, repetitive tasks with minimal regulatory overlay, low switching costs, and data that can be replicated or scraped via APIs. AI doesn’t need to understand your business to do what these tools do. It just needs to follow a script.

Customer service pure-plays like Freshworks and the now-private Zendesk sit here. So do SMB marketing automation tools, basic project management software, and simple invoicing platforms. Five9, which automates contact centre workflows, has gone from a $209 all-time high to roughly $18. That’s not a selloff; that’s a market pricing in obsolescence. Freshworks is trading at a 36% discount to its 52-week high with net dollar retention of just 105%, barely above the churn line.

The tell for Dead Zone companies is straightforward: if Claude Cowork’s plugins can replicate your core value proposition out of the box, your moat was never a moat. It was a feature wrapped in a subscription. These companies sell outcomes that are increasingly achievable through general-purpose AI agents, and the pricing pressure will be relentless. When Anthropic launches legal, finance, marketing, and customer support plugins under an open-source licence, every company whose primary offering overlaps with those categories needs to articulate why they’re worth paying for.

Some of them can’t.

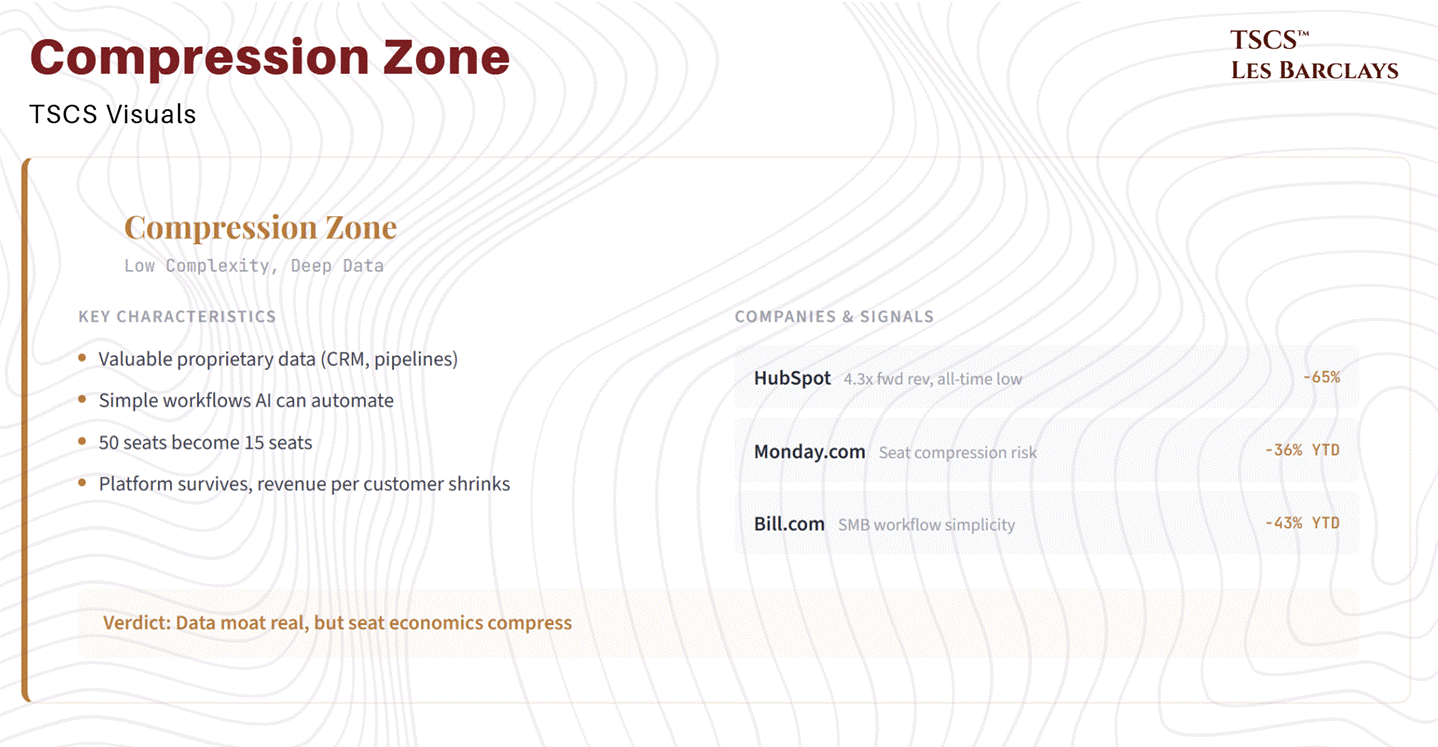

Quadrant 2: The Compression Zone (Low Complexity, Deep Data)

This is the trickiest quadrant for investors, because the data moat is real but the workflow simplicity means AI compresses the value of human seats interacting with that data. The data delays disruption, but it doesn’t prevent it.

HubSpot is the canonical example. Its CRM data is genuinely valuable (customer interaction histories, pipeline data, attribution models), but the SMB workflows built on top of that data are simple enough that an AI agent can execute most of them without human intervention. The result isn’t that HubSpot dies, it’s that a company paying for 50 seats suddenly needs 15. Revenue per customer compresses even as the platform remains sticky.

HubSpot’s 65% stock decline isn’t just panic selling. It’s the market repricing a business where seat-based economics face structural compression. At 4.3x forward revenue, it trades at all-time low multiples. The question isn’t whether HubSpot survives (it probably does), it’s whether the revenue model can adapt fast enough to offset the seat destruction. Management is guiding for 16% revenue growth in 2026, down from 21% in Q3 2025. That deceleration trajectory matters.

Analytics platforms and basic BI tools also sit here. The data they house can be valuable, but the act of querying, visualising, and summarising that data is precisely what LLMs are getting better at every quarter.

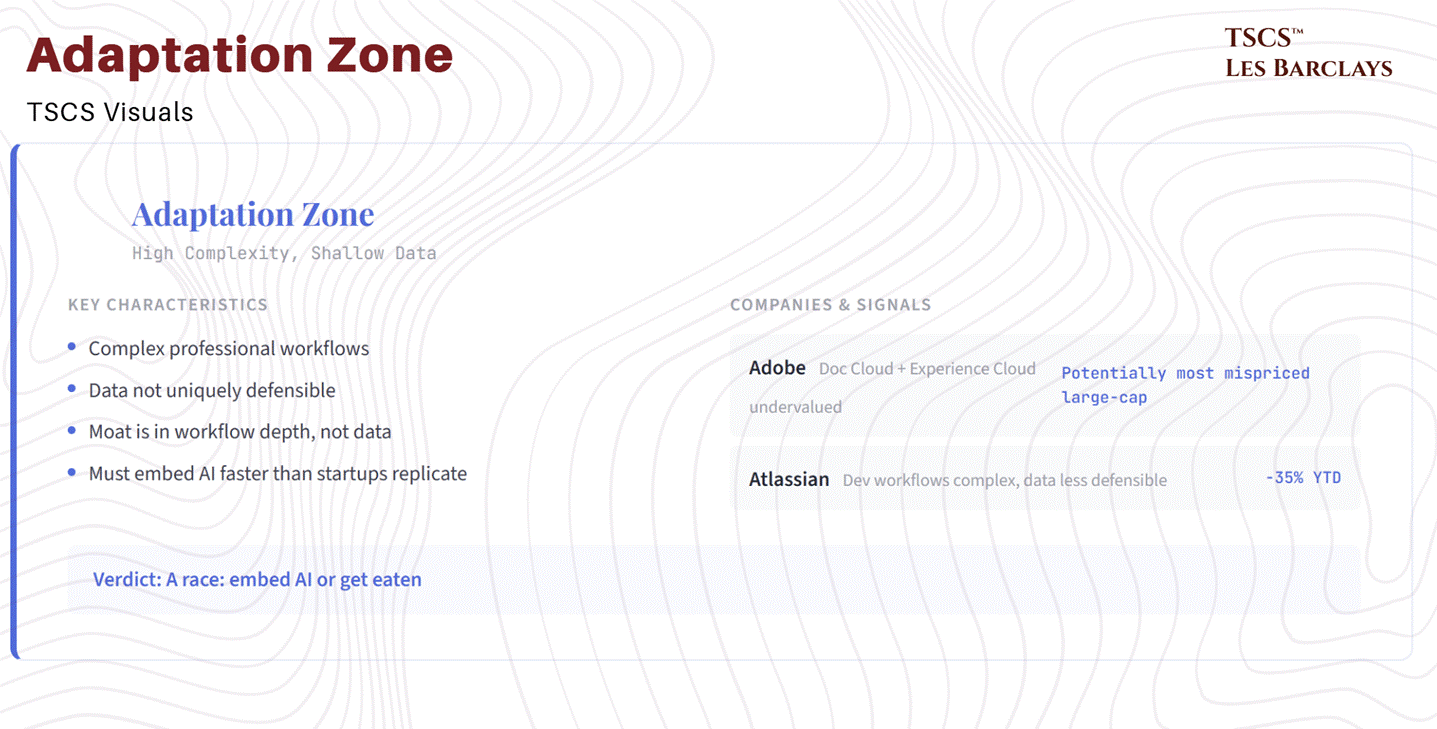

Quadrant 3: The Adaptation Zone (High Complexity, Shallow Data)

These companies operate in genuinely complex workflow environments, but the data they hold isn’t uniquely defensible. The moat is in the workflow depth, not the data. They survive by embedding AI into their workflows faster than AI-native startups can replicate their workflow complexity.

Adobe is the most interesting name here, and potentially the most mispriced large-cap in the entire software universe. The market is pricing it as if it’s only a creative tools company, when Document Cloud and Experience Cloud (enterprise digital marketing) are growing at or above the group rate and have zero overlap with text-to-image AI generation. The enterprise installed base, the workflow lock-in from Premiere to After Effects to Illustrator pipelines, and the sheer depth of professional creative workflows create switching costs that a text prompt cannot replicate. The question for Adobe is the same one it faced during the cloud transition: Is it Kodak, or is it Microsoft? We develop the full investment case in Section 7.

Atlassian sits here too, down 35% YTD. Development workflows are complex, but Jira’s data (tickets, sprint boards, backlogs) isn’t uniquely defensible. If Atlassian can’t embed AI deeply enough into the development lifecycle, faster-moving AI-native project tools will eat its lunch. It’s a race, and unlike Adobe, Atlassian doesn’t have the same margin of safety in its valuation.

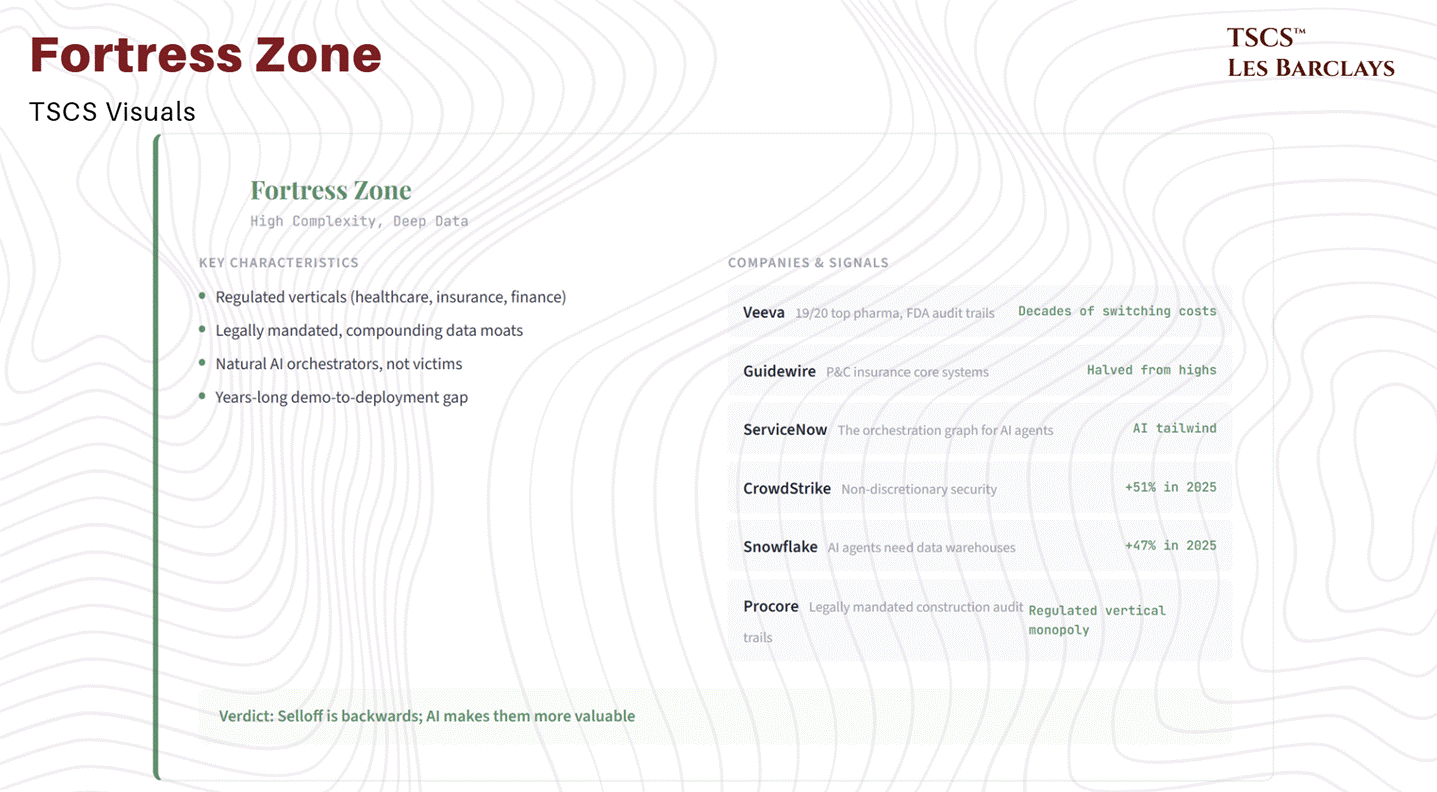

Quadrant 4: The Fortress Zone (High Complexity, Deep Data)

This is where the selloff is not just wrong, it’s backwards. These companies don’t get disrupted by AI. They get more valuable because of it.

Fortress Zone companies share three characteristics. First, they operate in regulated verticals where compliance itself is the product (healthcare, insurance, financial services, construction, government). Second, their data moats are institutional, compounding, and legally mandated, not just commercially useful. Third, the complexity of their workflows makes them natural orchestrators of AI rather than victims of it.

Veeva Systems serves 19 of the top 20 pharmaceutical companies in a regulatory environment where FDA-validated audit trails create decades of compounding switching costs. No AI-native entrant can shortcut that institutional trust.

Guidewire is the dominant platform for property and casualty insurance core systems, operating in a regulatory environment where actuarial history, policy complexity, and compliance requirements make the demo-to-deployment gap measured in years, not months. The selloff here is sector contagion, not fundamental deterioration.

Procore in construction has legally mandated audit trails where system downtime means capital cannot deploy. The market is treating a regulated vertical monopoly like a generic SaaS tool.

ServiceNow is the orchestration graph. It doesn’t compete with AI agents; it’s the platform AI agents need to operate through. When an enterprise deploys agentic workflows, those agents need to interact with IT systems, HR processes, customer service queues, and security protocols. ServiceNow routes, governs, and audits those interactions.

CrowdStrike sits at the intersection of non-discretionary security spending and AI-driven attack surface expansion. Every argument the bears make about AI disrupting SaaS is an argument for spending more on security.

Snowflake’s consumption model directly benefits from AI workloads, because every AI agent needs to query data somewhere, and “somewhere” is increasingly a data warehouse or lakehouse.

We develop investment cases for each of these names in Section 7, with specific valuations, risk factors, and conviction levels.

The pattern should be obvious by now.

The Market Is Already Telling You

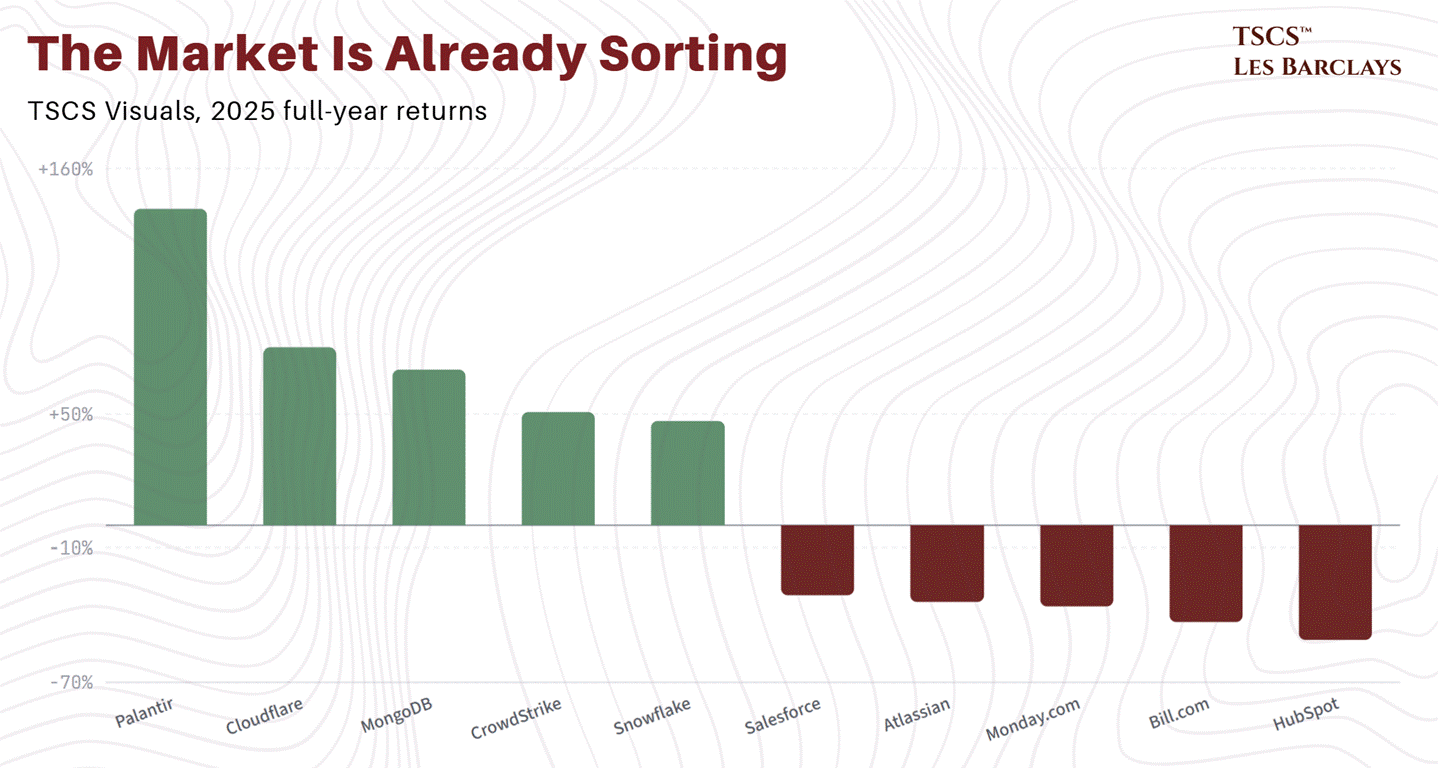

The SaaStr year-end data from December 2025 quantified the bifurcation perfectly. Palantir: +142%. Cloudflare: +80%. MongoDB: +70%. CrowdStrike: +51%. Snowflake: +47%. Those are 2025 full-year returns. On the other side: HubSpot: -51%. Bill.com: -43%. Monday.com: -36%. Atlassian: -34%. Salesforce: -31%.

That’s not random dispersion. That’s the market sorting companies into quadrants in real time, even if it can’t articulate the framework. The companies gaining are either AI-native from inception (Palantir), essential infrastructure that AI depends on (Snowflake, MongoDB, Cloudflare), or non-discretionary security that AI’s proliferation makes more critical (CrowdStrike). The companies losing are those where seat-based economics face compression, workflow complexity is moderate, or the moat was always thinner than the multiple implied.

What the 2026 selloff has done is extend the punishment indiscriminately, dragging Fortress Zone names down alongside Dead Zone names. That’s where the opportunity lives. When IGV is down 25% YTD and Guidewire has been halved from its highs, the market is not pricing in nuance. It’s pricing in fear. And fear is not an investment thesis.

The question for Section 7 is straightforward: which specific names in the Fortress Zone are the most compelling risk/reward right now, and where is the selloff actually justified?

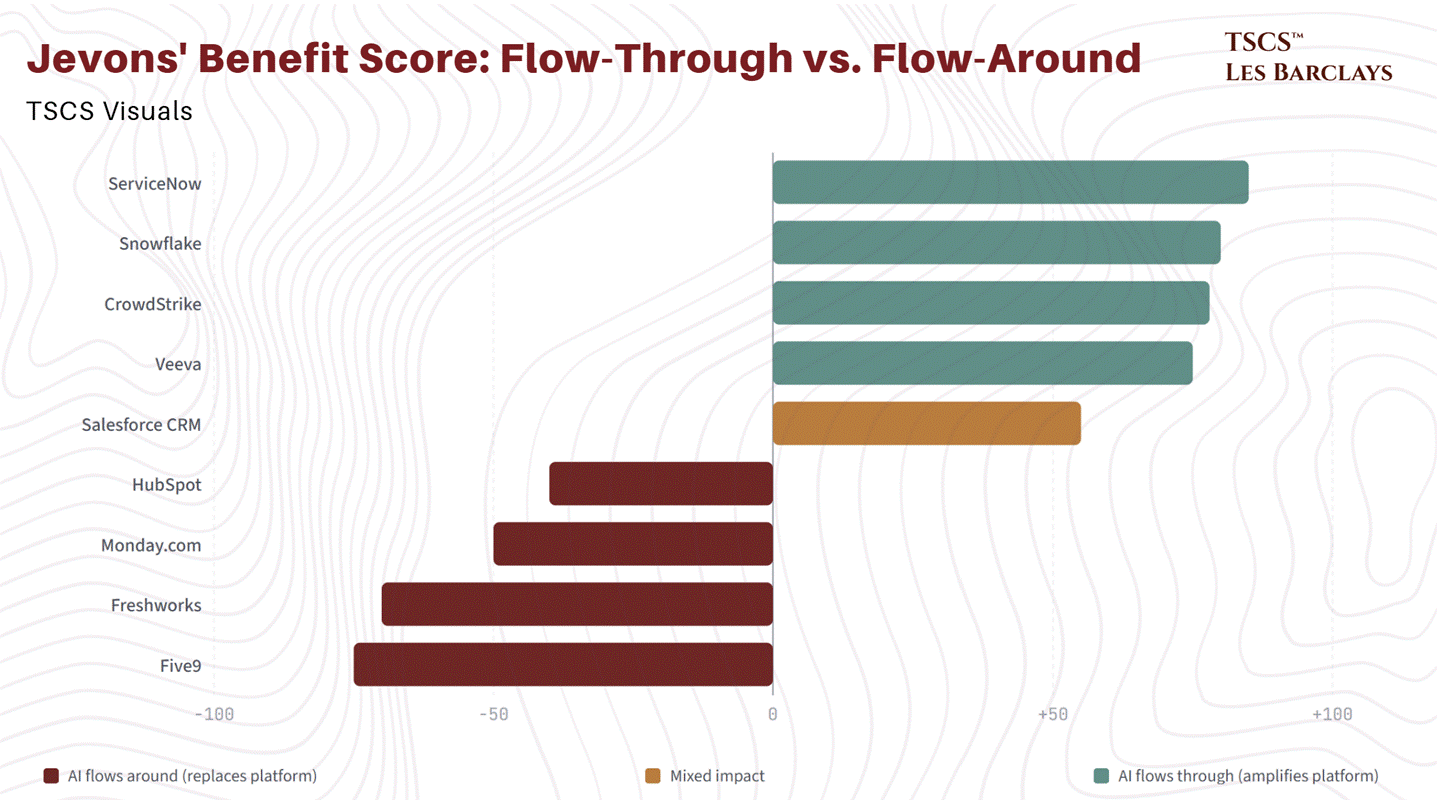

Section 6: Jevons’ Paradox

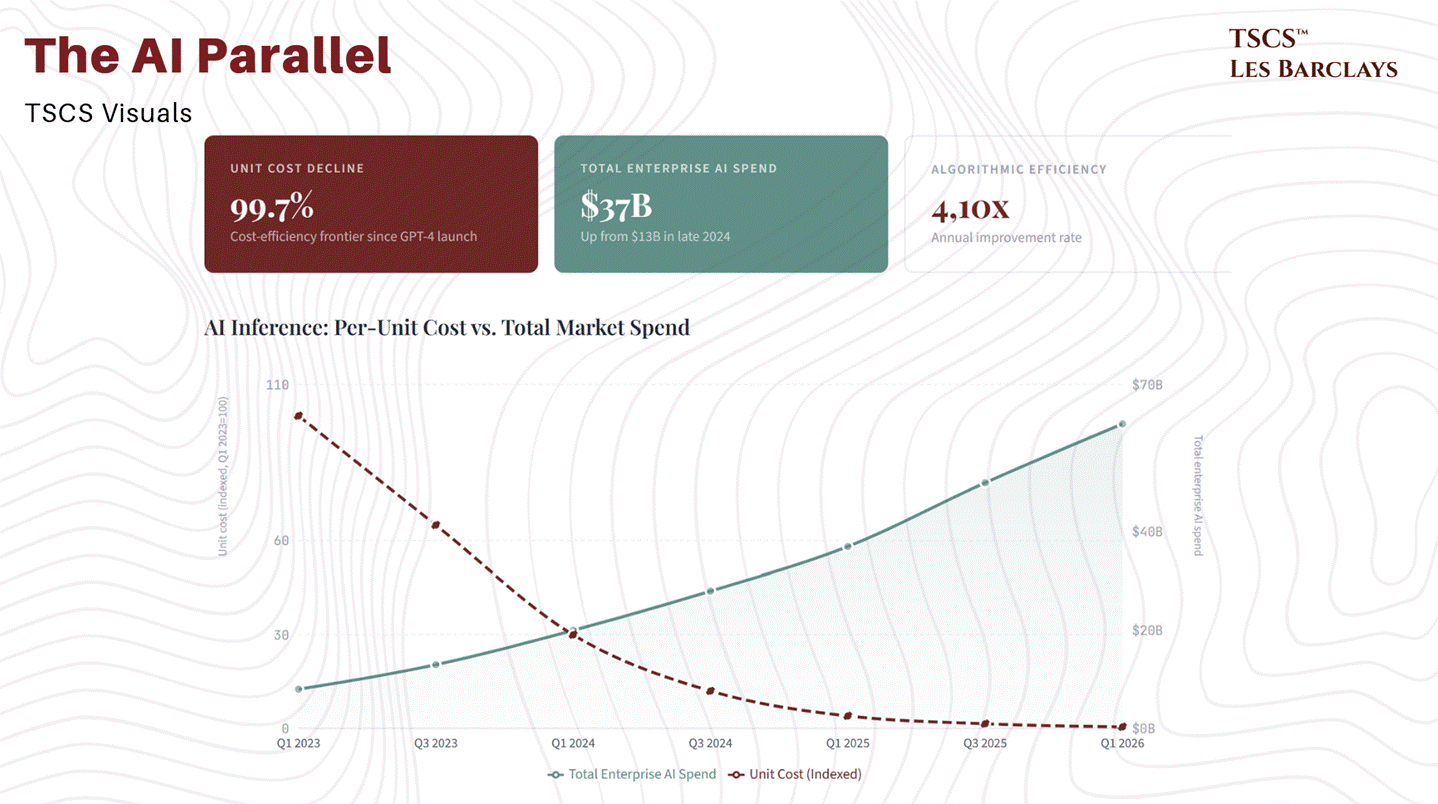

Section 3 laid out the freefall in model pricing: a 99.7% decline in the cost-efficiency frontier since March 2023, algorithmic improvements boosting efficiency 4-10x annually, and inference costs being slashed fivefold in a matter of months. The marginal cost of intelligence is trending toward zero.

The consensus interpretation of this data is bearish for the model layer (correct) and bearish for total AI spending (almost certainly wrong). This is where Jevons’ Paradox enters the picture, and where the implications for SaaS become genuinely interesting.

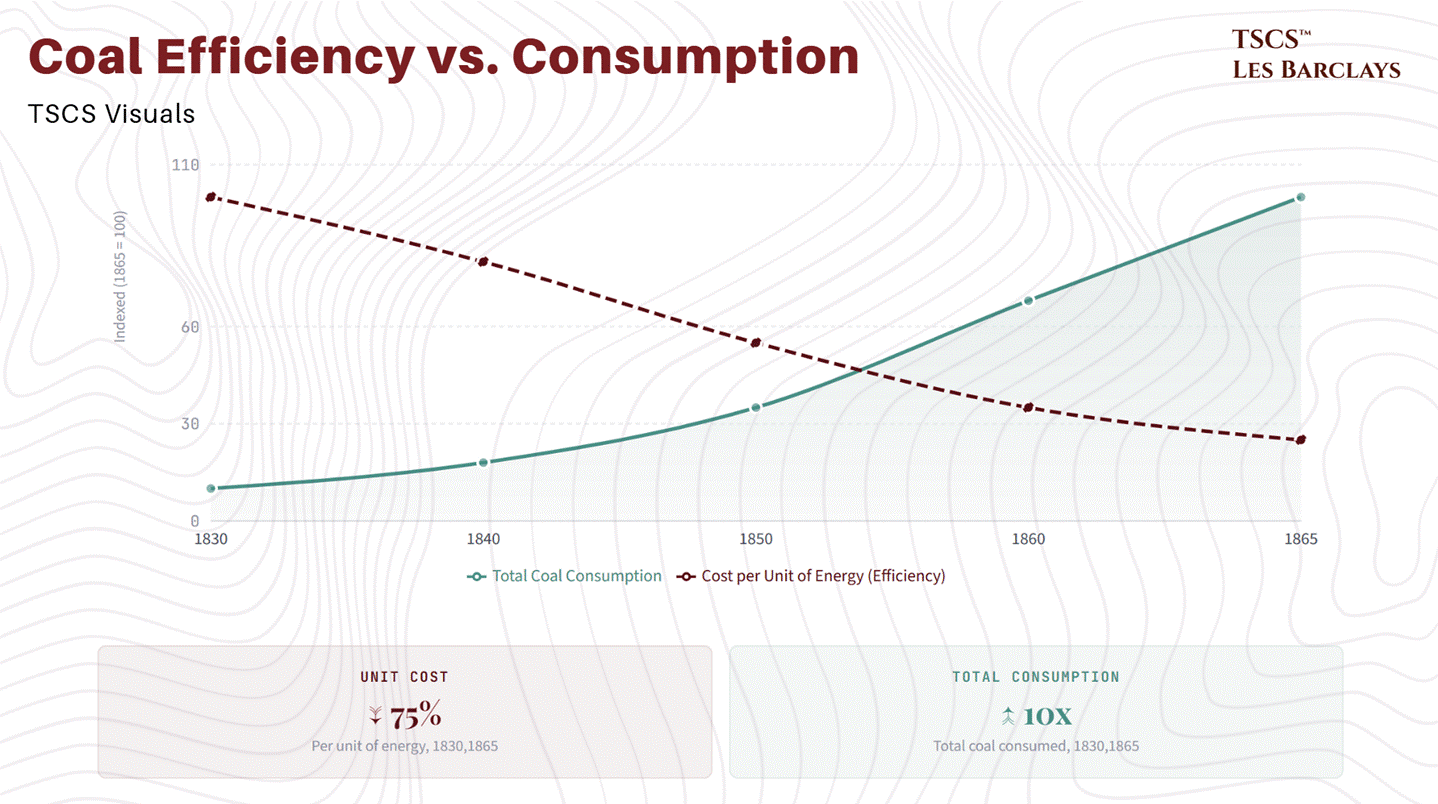

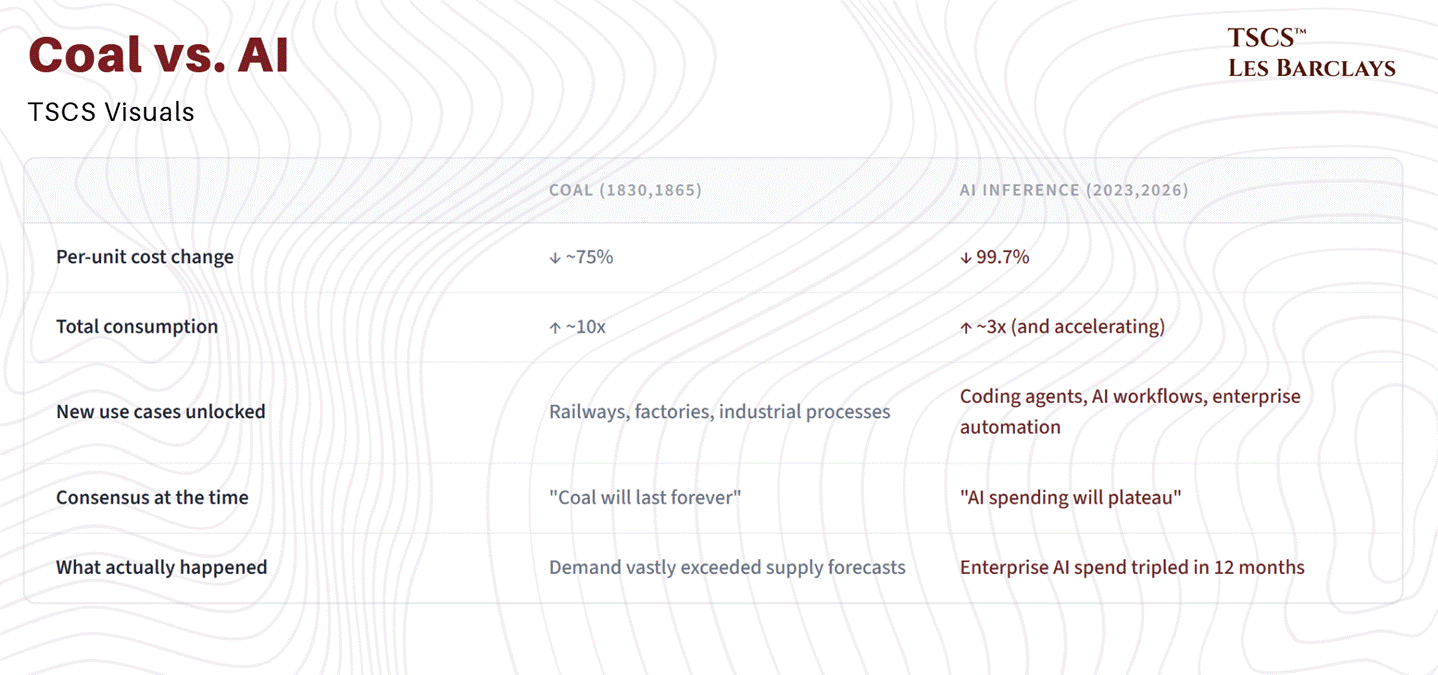

William Stanley Jevons observed in 1865 that as coal-powered steam engines became more efficient, total coal consumption increased rather than decreased, because cheaper energy unlocked use cases that were previously uneconomical. The same dynamic is playing out in AI. As inference becomes cheaper, the number of viable applications expands dramatically, and total compute spending rises even as the per-unit cost collapses.

The early evidence supports this. The rapid adoption of AI coding tools hasn’t led to fewer developers being needed; it’s led to more complex software being built. Companies that would never have deployed AI at $37.50 per million tokens are deploying it aggressively at $0.14. The race to build more efficient models could fuel an exponential rise in overall GPU demand and electricity consumption rather than stabilising it.

As we noted in our earlier analysis of AI inference economics, the widely quoted compute margin of 70% for OpenAI requires careful interpretation. That metric measures margins on compute infrastructure costs alone: for every $1 collected from API usage or subscriptions, 30 cents goes toward GPU time, energy, and direct infrastructure overhead. It excludes R&D, talent, sales, and the continuous investment required to train successive frontier models. The all-in picture, as Section 3 detailed, is far less rosy. But the volume story is unambiguously bullish.

This has three implications for the SaaS thesis.

First, cheaper inference is a direct input cost reduction for SaaS incumbents. When it costs $0.14 per million tokens to run inference, embedding AI features into existing platforms becomes trivially cheap. The Fortress Zone companies identified in Section 4 can add AI capabilities at negligible marginal cost while maintaining premium pricing. The model layer bears the deflationary pressure; the application layer captures the surplus.

Second, Jevons’ Paradox means that every AI agent deployed by an enterprise needs to query, write to, and operate through existing systems of record. More agents means more API calls to Salesforce, more workflow transactions through ServiceNow, more data queries hitting Snowflake. The consumption rebound doesn’t just benefit GPU makers. It benefits the data and workflow infrastructure that AI operates through.

Third, the deflationary pressure on model pricing will eventually force model companies to integrate vertically into applications (as Anthropic is already doing with Cowork) or accept commodity returns. That vertical integration puts them in direct competition with entrenched incumbents on their home turf, a far harder fight than building a better model.

There’s a counterargument that deserves honest treatment. Jevons’ Paradox requires that cheaper inputs unlock genuinely new demand rather than merely substituting for existing spending. For coal, the new demand came from railways, factories, and industrial processes that didn’t exist before steam engines became efficient. The analogous question for AI is whether cheaper inference creates net new enterprise software spending, or whether it primarily redirects existing spending.

If a company uses cheap AI to eliminate 30 Salesforce seats, total software spending drops even if total compute spending rises. The Jevons’ framing only helps SaaS if the consumption rebound flows through existing platforms rather than around them. I think the evidence tilts toward “through” for Fortress Zone companies (more AI agents means more API calls to systems of record, more workflow transactions, more data queries) and “around” for Dead Zone companies (where the AI agent replaces both the human and the software the human used). The paradox is not uniformly bullish for SaaS. It’s bullish for the infrastructure layer that AI operates through, and bearish for the application layer that AI operates instead of. This reinforces the taxonomy from Section 4 rather than overriding it.

The market is pricing the decline in per-unit AI costs as a threat to software. It should be pricing it as a subsidy.

Section 7: The Equity Ideas

I’ve spent thousands of words building the framework. Now comes the part that actually matters: where to put capital.

The taxonomy from Section 5 gives us the filter. The selloff gives us the entry point. What follows is not a watchlist. It’s a ranked set of conviction ideas, each stress-tested against the framework, with specific data points that either support or undermine the thesis. I’ll flag what makes me nervous about each one, because any analyst who only gives you the bull case is either lazy or selling you something.

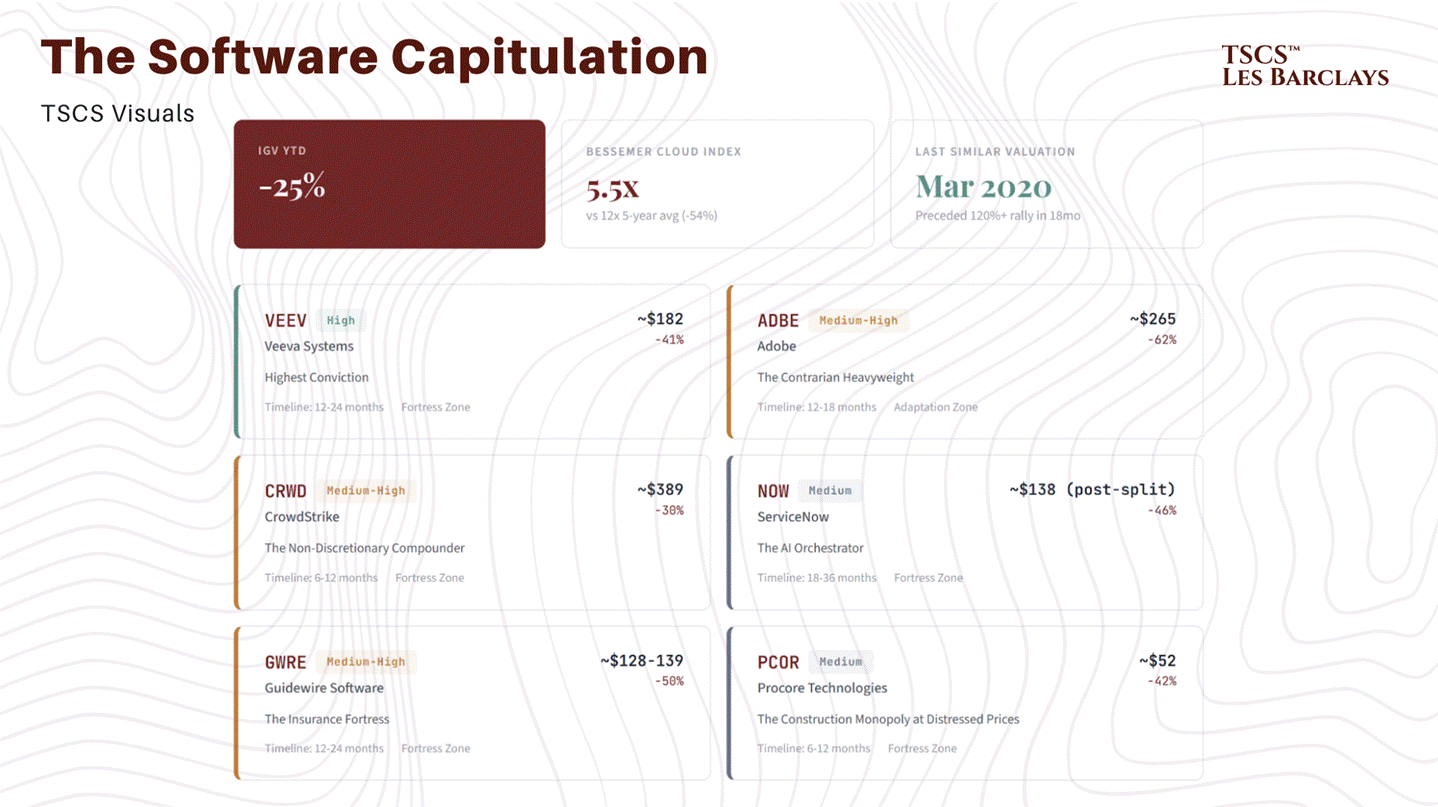

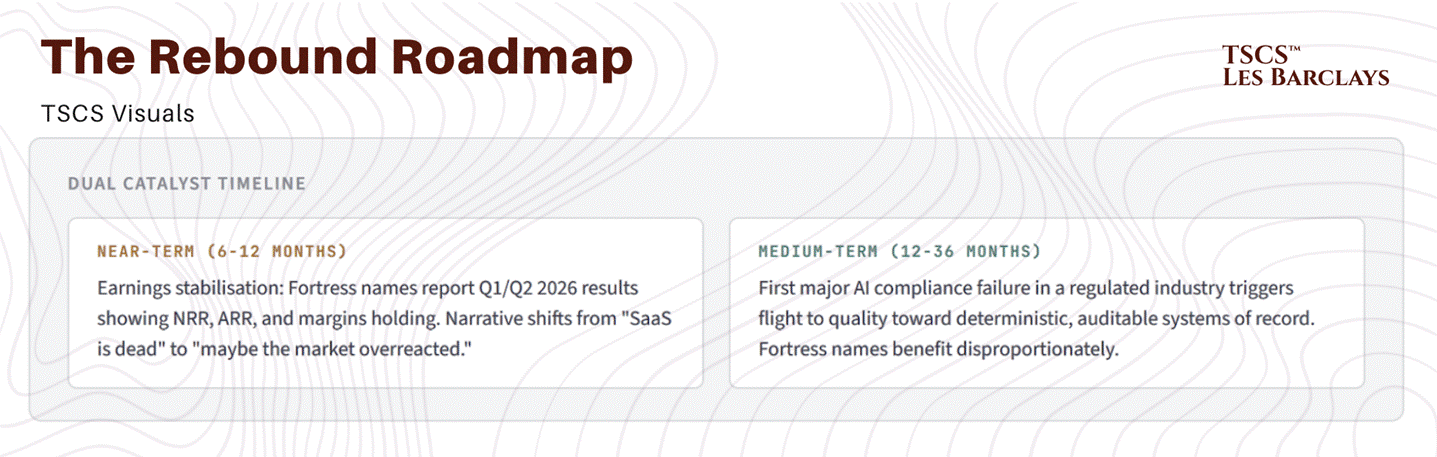

Before diving into individual names, the sector-level context matters. IGV, the iShares Expanded Tech-Software Sector ETF, is down 25% year-to-date. The Bessemer Cloud Index trades at roughly 5.5x forward revenue, compared to a five-year average of 12x. That’s a 54% discount to historical norms. The last time software valuations reached this level of compression was March 2020, which preceded a 120%+ rally over the following 18 months. I’m not predicting an identical rebound, but the base rate for buying quality software at these multiples has historically been very favourable over a 12-24 month horizon.

The thesis operates on two timelines. The near-term catalyst (6-12 months) is earnings stabilisation: when Fortress Zone companies report Q1 and Q2 2026 results showing that NRR, ARR growth, and margins are holding or accelerating despite the panic, the narrative shifts from “SaaS is dead” to “maybe the market overreacted.” The medium-term catalyst (12-36 months) is the first major AI compliance failure in a regulated industry, which triggers a flight to quality toward deterministic, auditable systems of record. Both catalysts are probabilistic, but the valuation floor means you’re being paid to wait.

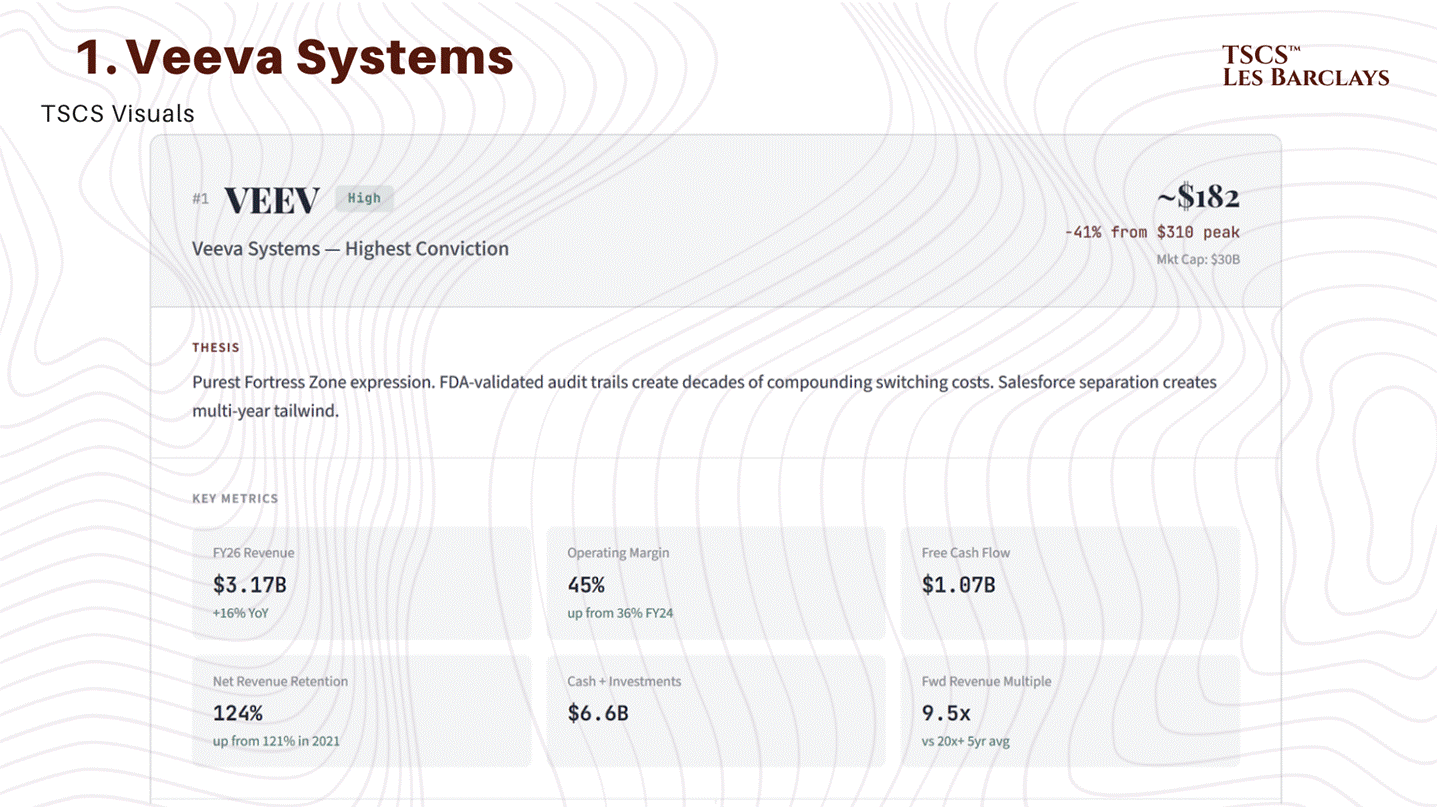

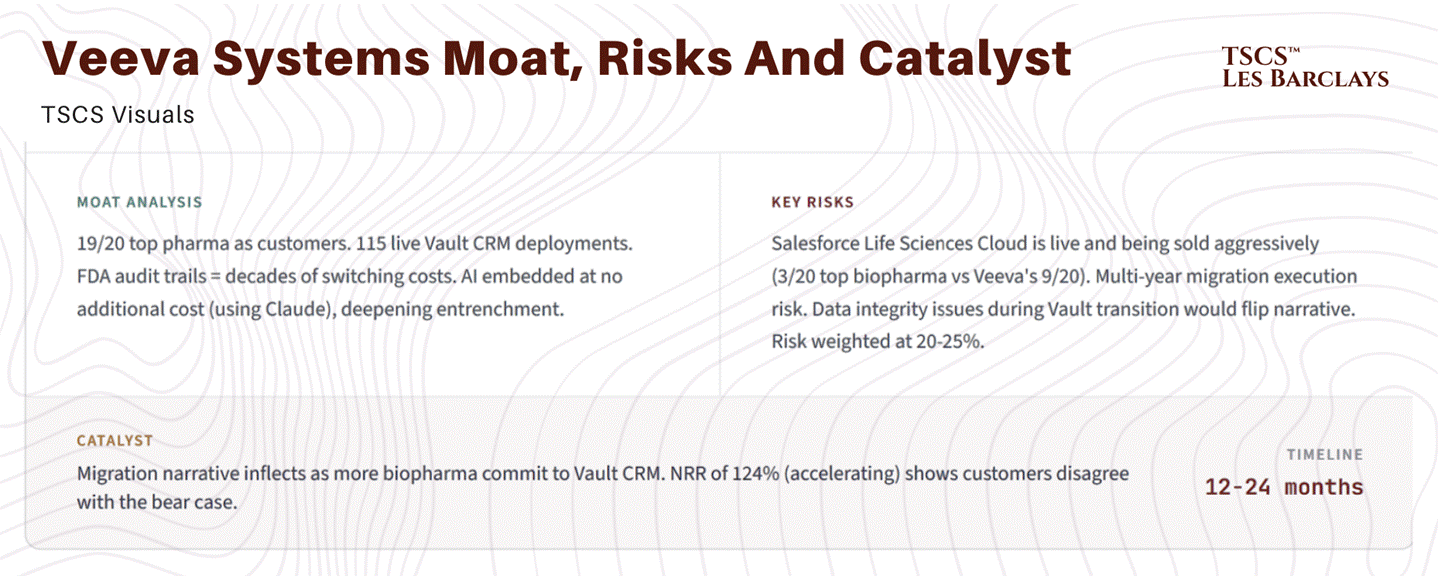

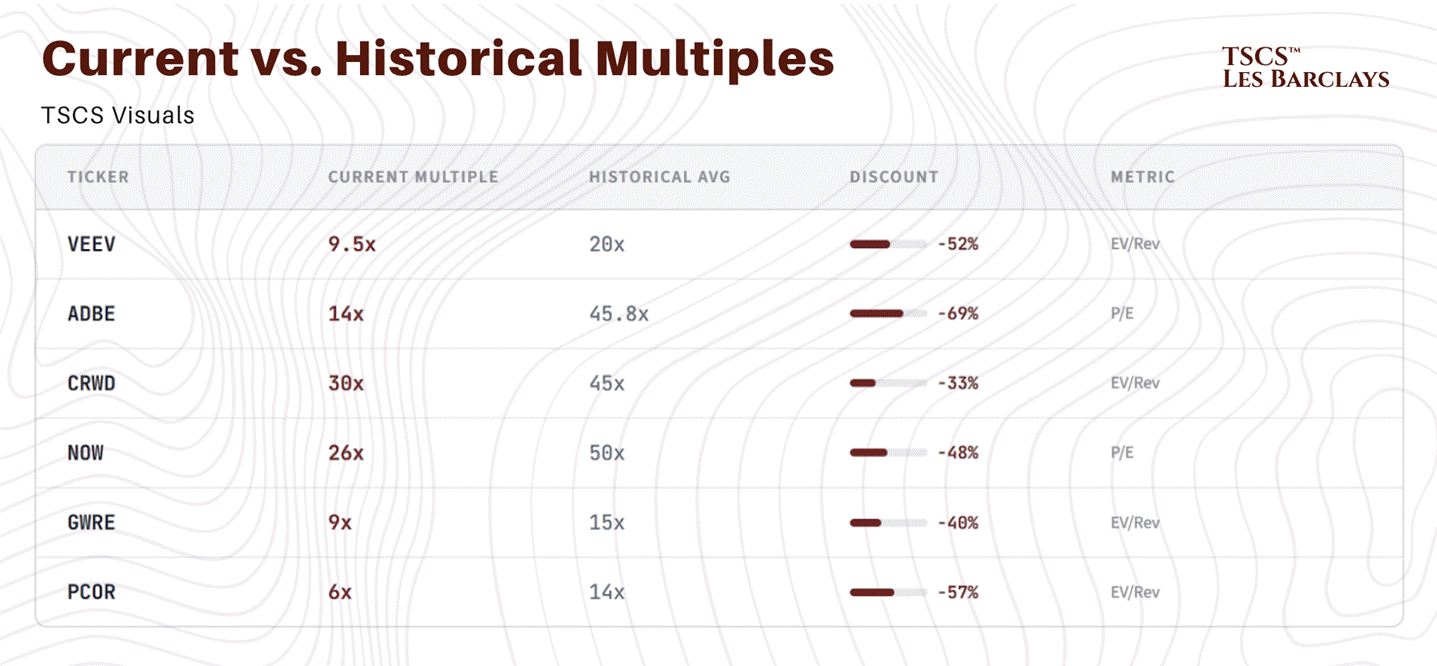

Idea #1: Veeva Systems (VEEV), Highest Conviction

Veeva is the purest expression of the Fortress Zone thesis. The stock has been halved, from $310 to roughly $182. Market cap is $30 billion. And yet the business is printing numbers that most SaaS companies would kill for.

The numbers: $3.17 billion in FY26 revenue guidance, 16% year-over-year growth, 45% non-GAAP operating margins (up from 36% in FY24), and $1.07 billion in free cash flow. Net revenue retention is 124%, which is up from 121% in 2021. Read that again. In a year where the market is pricing in SaaS destruction, Veeva’s existing customers are spending more, not less.

The moat is institutional, not technical. 19 of the top 20 pharmaceutical companies are customers. 115 live Vault CRM deployments globally. Every FDA-validated audit trail is another year of switching cost that compounds like interest. If you’re a pharma executive and someone suggests ripping out the system that stores your regulatory submissions, clinical trial data, and compliance documentation to replace it with a vibe-coded alternative, you’d rightly question their judgment.

What’s genuinely interesting is the Salesforce separation. Veeva completed its formal break from Salesforce’s platform in September 2025, migrating to its own Vault CRM. Nine of the top 20 biopharmas have committed to Vault CRM versus Salesforce’s three. That’s not a competitive battle; it’s a rout. And the migration creates a multi-year revenue tailwind as customers upgrade and consolidate onto Veeva’s own stack.

The company is also embedding AI (using Anthropic’s Claude models, ironically) through Veeva AI Agents for commercial and R&D applications. But here’s the key: they’re including it at no additional cost. This is the exact thing I outlined in Section 2. The Fortress companies use AI to deepen entrenchment, not to extract incremental subscription fees. The AI makes the platform stickier, not more expensive.

At $30 billion, you’re paying roughly 9.5x forward revenue for a company doing $3.17 billion growing at 16% with 45% operating margins and $6.6 billion in cash and short-term investments. For context, Veeva’s five-year average forward revenue multiple is north of 20x. The stock is being valued as though growth is about to stall, but NRR of 124% (accelerating, not decelerating) tells you existing customers disagree.

The risk is real, though, and I want to be specific about it. Salesforce’s Life Sciences Cloud is not a hypothetical competitor; it’s live and being sold aggressively. Three of the top 20 biopharmas have committed to Salesforce versus nine for Vault CRM. That’s a clear Veeva lead, but the migration itself is a multi-year execution gauntlet. If a major pharma experiences data integrity issues or regulatory complications during the Salesforce-to-Vault transition, the narrative flips from “Veeva is winning the migration” to “Veeva broke the migration.” I’d weight that risk at maybe 20-25% over the next two years.

Despite that, the risk/reward skews heavily in Veeva’s favour. The downside is a company that still grows at 12-14% with best-in-class margins and a fortress balance sheet. The upside is a re-rating toward historical multiples as the migration proves out and AI embedding deepens the moat. I’m not going to call this a once-in-a-cycle opportunity because I think intellectual honesty requires acknowledging that the Salesforce risk is material, but it is the single name I find most compelling in the Fortress Zone.

Conviction: High. Timeline: 12-24 months for the migration narrative to inflect positively.

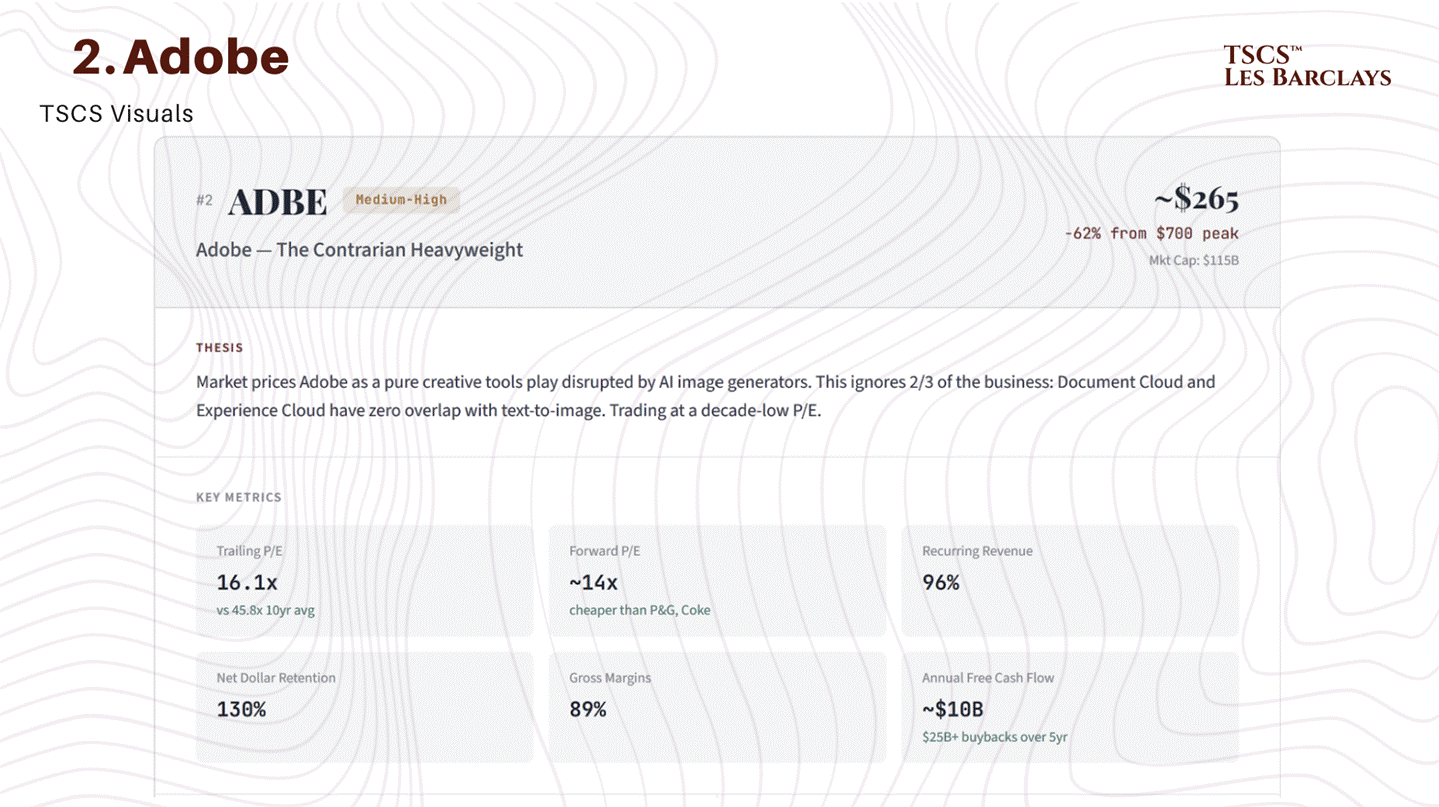

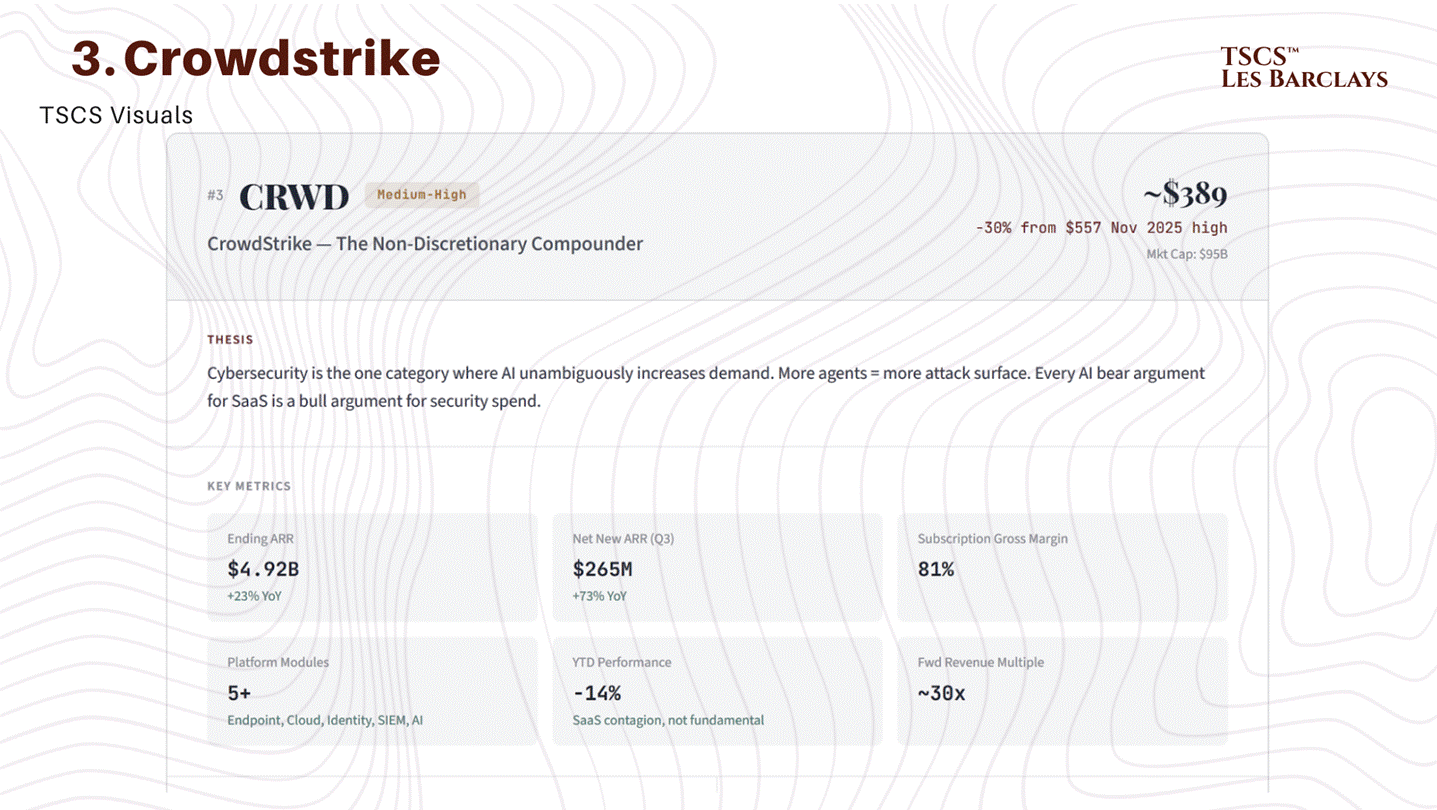

Idea #2: Adobe (ADBE), The Contrarian Heavyweight

Adobe trades at 16.1x trailing earnings. The 10-year average P/E is 45.8x. The forward P/E is approximately 14x. For context, that’s cheaper than Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, and most consumer staples companies that grow at half Adobe’s rate. The market is pricing a $265 stock as if it’s a value trap. It’s not.

Here’s what the market is getting wrong. The bear case treats Adobe as a pure creative tools play that gets disrupted by generative AI image generators. That framing ignores two-thirds of the business. Document Cloud (Acrobat, PDF services) and Experience Cloud (enterprise digital marketing, analytics, commerce) are growing at or above the group rate and have zero overlap with text-to-image AI generation. The PDF is not getting disrupted by Midjourney.

The numbers that matter: 96% recurring revenue, 130% net dollar retention, 89% gross margins, and roughly $10 billion in annual free cash flow. Adobe generated more free cash flow last year than Snowflake, CrowdStrike, and Veeva combined. The company has repurchased over $25 billion in stock over the past five years. It’s a cash generation machine trading at a decade-low multiple.

I keep coming back to the cloud transition analogy. In 2012-2013, Wall Street declared Adobe dead because Creative Suite was going subscription-only and piracy would kill them. The stock went from $32 to what was eventually a $700 peak. The bears were focused on the transition risk and completely missed the TAM expansion. We may be watching the same movie. The market is fixated on the Photoshop disruption narrative while the broader Adobe platform, which spans content creation, document management, and enterprise marketing, becomes the operating system for enterprise content workflows in an AI world.

The risk: Creative Cloud is genuinely exposed to erosion at the low end. Canva, Figma (which Adobe failed to acquire), and AI image generators will eat the casual creator market. If Adobe can’t retain the prosumer tier, revenue growth stalls and the multiple stays compressed. There’s also the question of whether Firefly is a genuine differentiator or just a defensive product. I think the former, but I hold that view with moderate confidence.

Conviction: Medium-High. Timeline: this is the longest-duration idea in the portfolio. The valuation floor limits downside, but the narrative may take 12-18 months to shift. The re-rating catalyst is likely a quarter where Document Cloud and Experience Cloud growth re-accelerates visibly enough to break the “Adobe = Photoshop” framing.

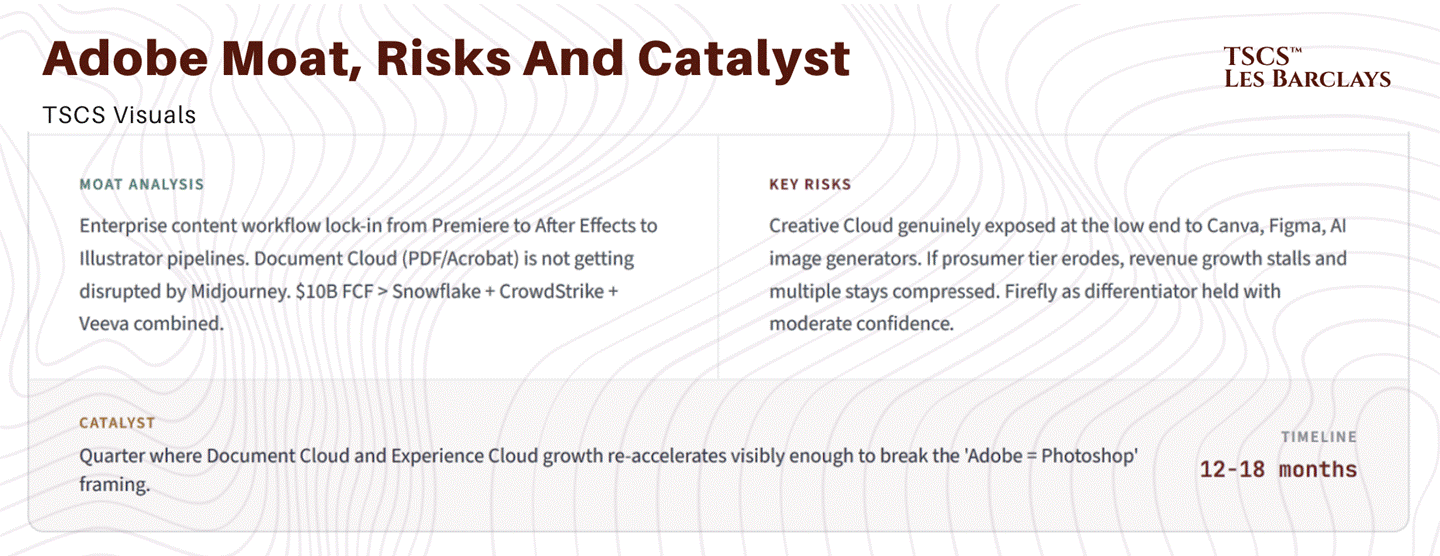

Idea #3: CrowdStrike (CRWD), The Non-Discretionary Compounder

Cybersecurity is the one software category where AI unambiguously increases demand. More AI agents means more attack surface. More automated workflows means more endpoints to secure. More data flowing through enterprise systems means more vectors for breach. Every argument the bears make about AI disrupting SaaS is an argument for spending more on security.

CrowdStrike just posted record Q3 Net New ARR of $265 million, up 73% year-over-year. Ending ARR is $4.92 billion, growing at 23%. Subscription gross margins are 81%. The Falcon platform is consolidating security spending across endpoint, cloud, identity, and SIEM, which is exactly the platform-level integration that protects companies from the “feature moat” erosion I described in Section 1.

At roughly $389, the stock is down 30% from its November 2025 high of $557 and 14% year-to-date. That’s the SaaS contagion effect. CrowdStrike is being sold alongside Freshworks and Five9 as if they face the same fundamental threat. They don’t. Morgan Stanley’s CIO survey shows enterprise cybersecurity budgets growing 50% faster than overall software spending. This is the one line item a CFO cannot cut.

One objection worth addressing head-on: I’ve argued throughout this piece that “feature moats” are vulnerable while “platform moats” are defensible. A fair critic would point out that CrowdStrike’s own rise was built on displacing legacy antivirus vendors whose endpoint protection was, at the time, considered a platform. The distinction between feature and platform is not static; it depends on the pace of consolidation and the competitive response. The reason I place CrowdStrike in the Fortress category rather than the Adaptation category is the breadth of its current platform (endpoint, cloud, identity, SIEM, and now AI security) combined with the non-discretionary nature of the spending. Displacing CrowdStrike today would require replicating not just one capability but an integrated security fabric across multiple domains. That’s a fundamentally different competitive dynamic than displacing a single-point antivirus product. But I hold this view with less certainty than the Veeva thesis, because Microsoft’s bundling strategy with Defender and Copilot Security is exactly the kind of platform consolidation play that could compress CrowdStrike’s standalone value over a 3-5 year horizon.

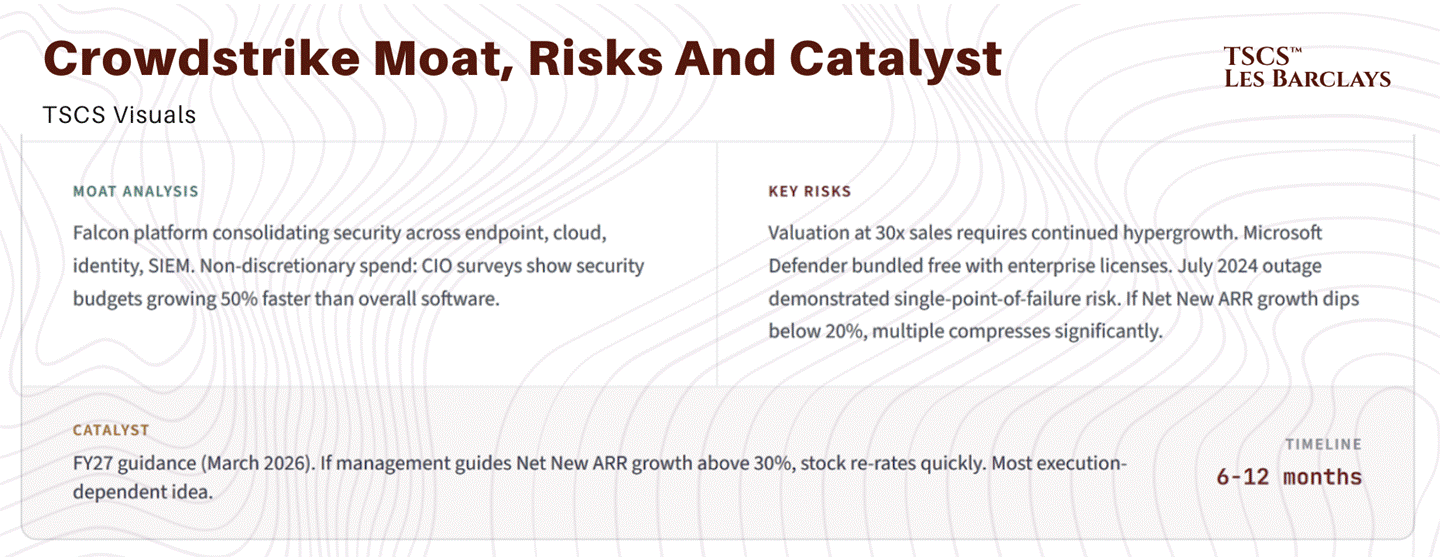

The risk: Valuation. At 30x sales and a negative GAAP P/E, CrowdStrike requires continued hypergrowth to justify the premium. Microsoft Defender is bundled free with enterprise licences and represents genuine competitive pressure. And the July 2024 outage, while operationally resolved, demonstrated single-point-of-failure risk that enterprise procurement teams haven’t forgotten. If Net New ARR growth decelerates below 20% in FY27, the multiple compresses significantly.

Conviction: Medium-High. Timeline: 6-12 months. The near-term catalyst is FY27 guidance (expected March 2026). If management guides Net New ARR growth above 30%, the stock re-rates quickly. This is the most execution-dependent idea in the portfolio.

Idea #4: ServiceNow (NOW), The AI Orchestrator

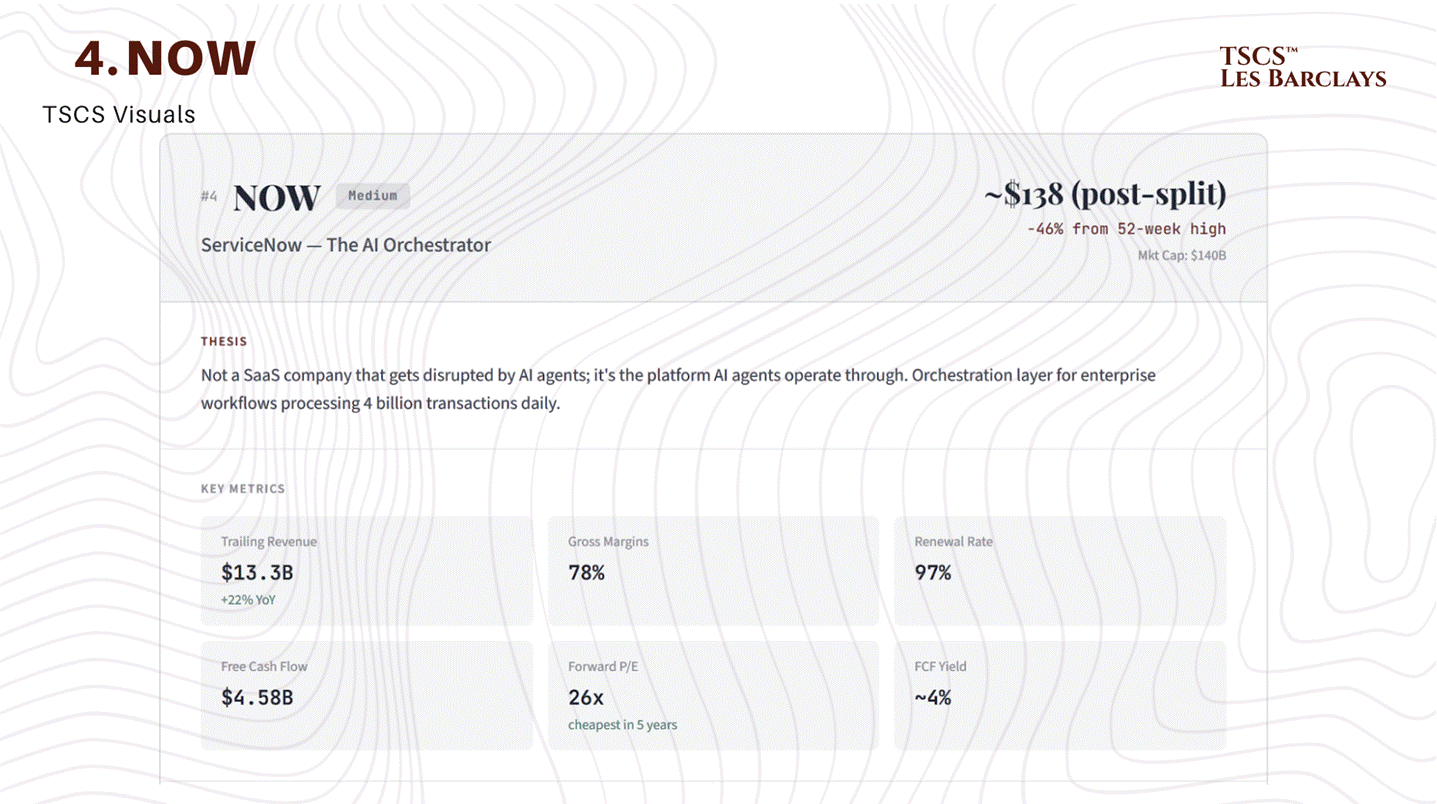

ServiceNow is the name I’ve spent the most time debating internally because the stock decline has been savage: down 46% over the past year. After its 5:1 stock split in December 2025, shares trade around $138. For a business doing $13.3 billion in trailing revenue growing at 22%, with 78% gross margins, a 97% renewal rate, and $4.58 billion in free cash flow, that is a remarkable de-rating.

The bull case is that ServiceNow isn’t a SaaS company that gets disrupted by AI agents, it’s the platform AI agents operate through. When an enterprise deploys agentic workflows, those agents need to interact with IT systems, HR processes, customer service queues, and security protocols. ServiceNow is the orchestration layer that routes, governs, and audits those interactions. Bill McDermott’s “semantic layer for AI” positioning sounds like marketing, but the underlying logic is sound: AI agents need a system of record to operate within, and ServiceNow processes 4 billion workflow transactions daily across the world’s largest enterprises.

The $7.75 billion Armis acquisition, expected to close in H2 2026, adds cybersecurity to the platform, which further entrenches ServiceNow as the enterprise control plane.

At a forward P/E of 26x and a free cash flow yield of roughly 4%, ServiceNow is trading at its cheapest valuation in five years. Dan Ives at Wedbush called the software selloff a “table pounder moment to buy.” He may be early, but I don’t think he’s wrong on names like this.

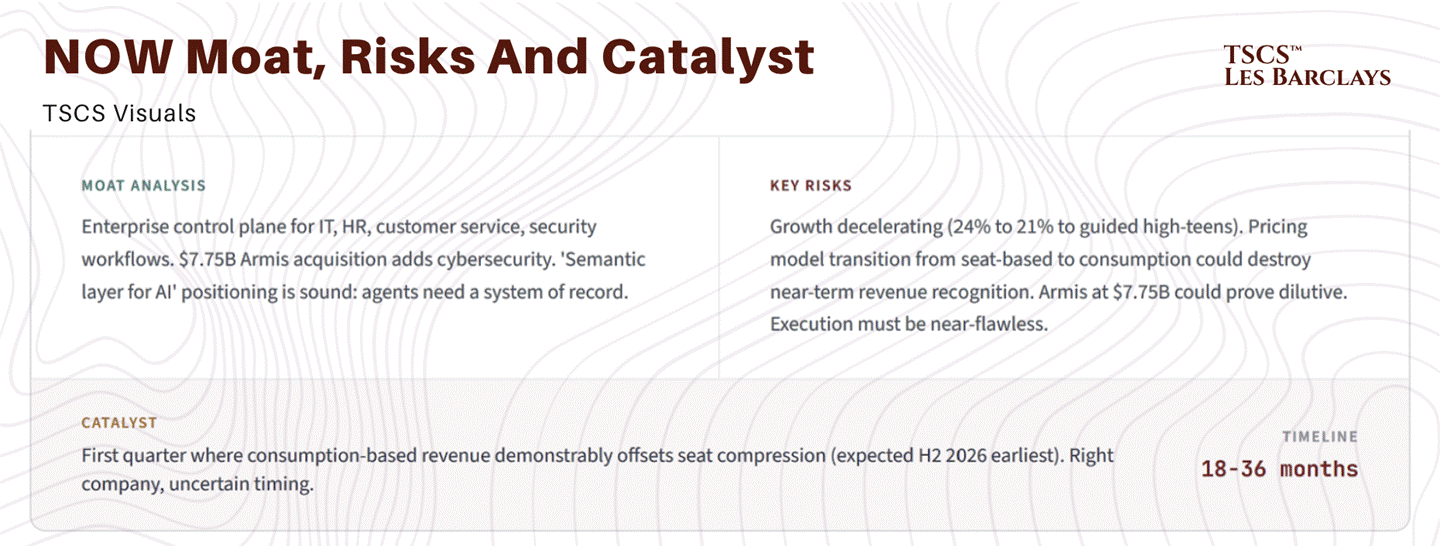

The risk: ServiceNow’s growth is decelerating (from 24% to 21% to guided high-teens). In a seat compression world, the question is whether ServiceNow can transition to consumption-based pricing without destroying near-term economics. The Armis acquisition at $7.75 billion is a large bet that could prove dilutive if integration stumbles. And at $138 per share, the stock is still pricing in substantial growth, just not as much as before.

This is the name where I’m genuinely torn. The thesis is sound: ServiceNow is the orchestration layer, not the disrupted application. But the growth deceleration (from 24% to 21% to guided high-teens) combined with the $7.75 billion Armis bet means execution has to be near-flawless to justify even the compressed multiple. I’d call this a “right company, uncertain timing” situation. The entry point is attractive if you have a 2-3 year horizon and patience for potential near-term multiple compression as the pricing model transitions.

Conviction: Medium. Timeline: 18-36 months. This requires patience through a pricing model transition. The catalyst is the first quarter where consumption-based revenue demonstrably offsets seat compression, which I don’t expect until H2 2026 at the earliest.

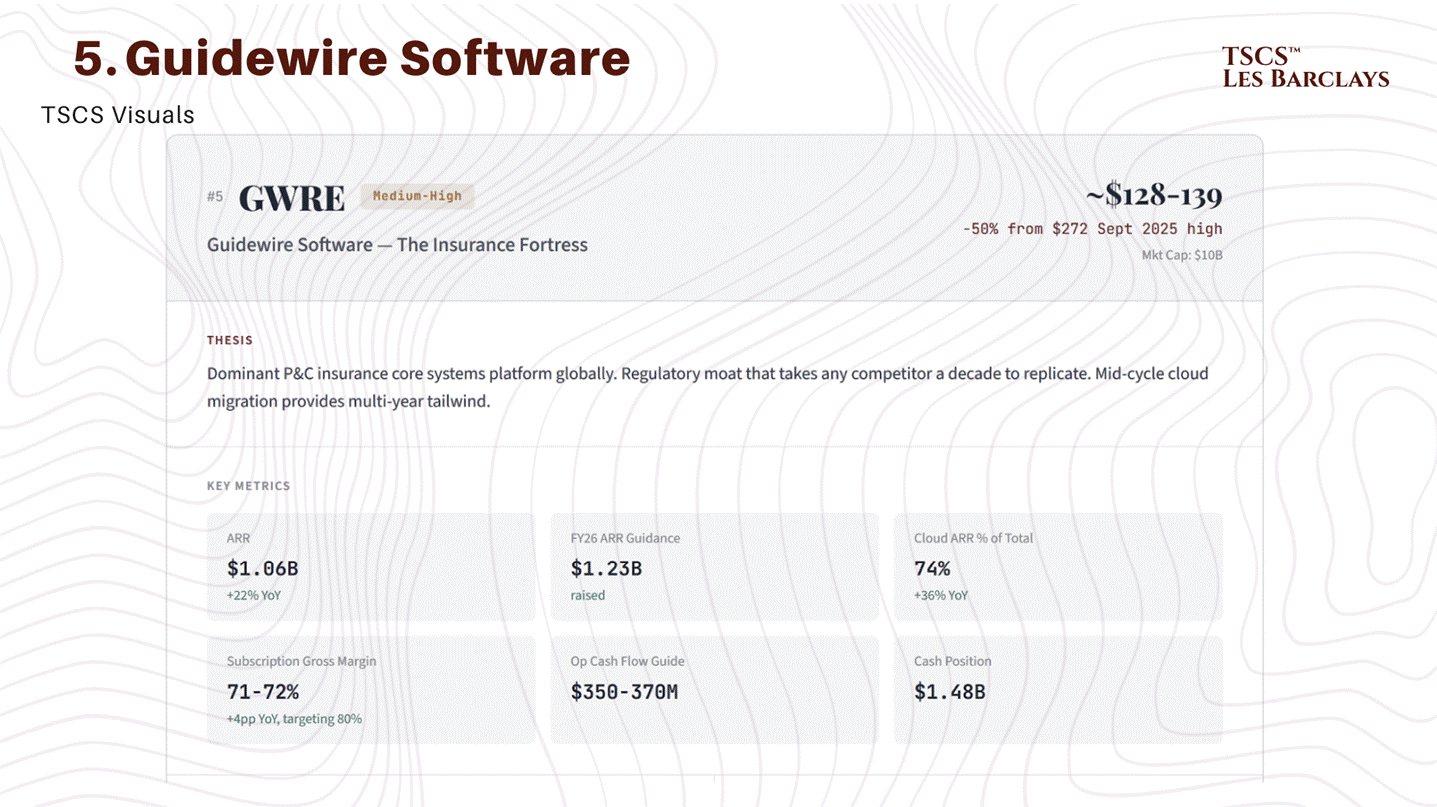

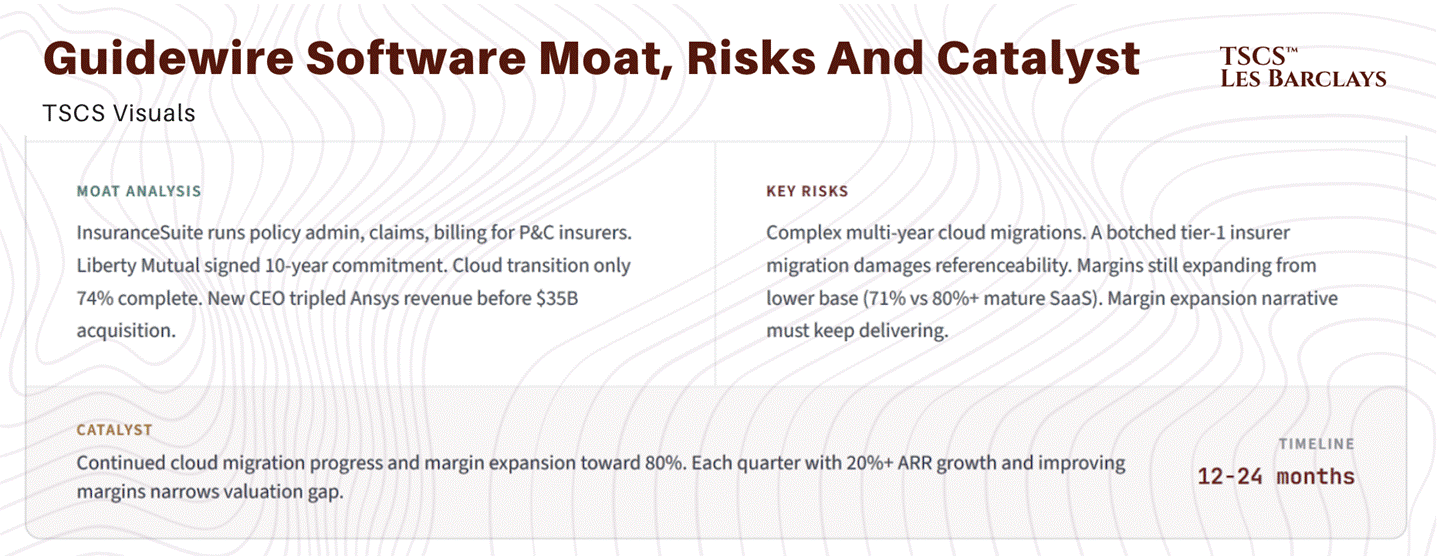

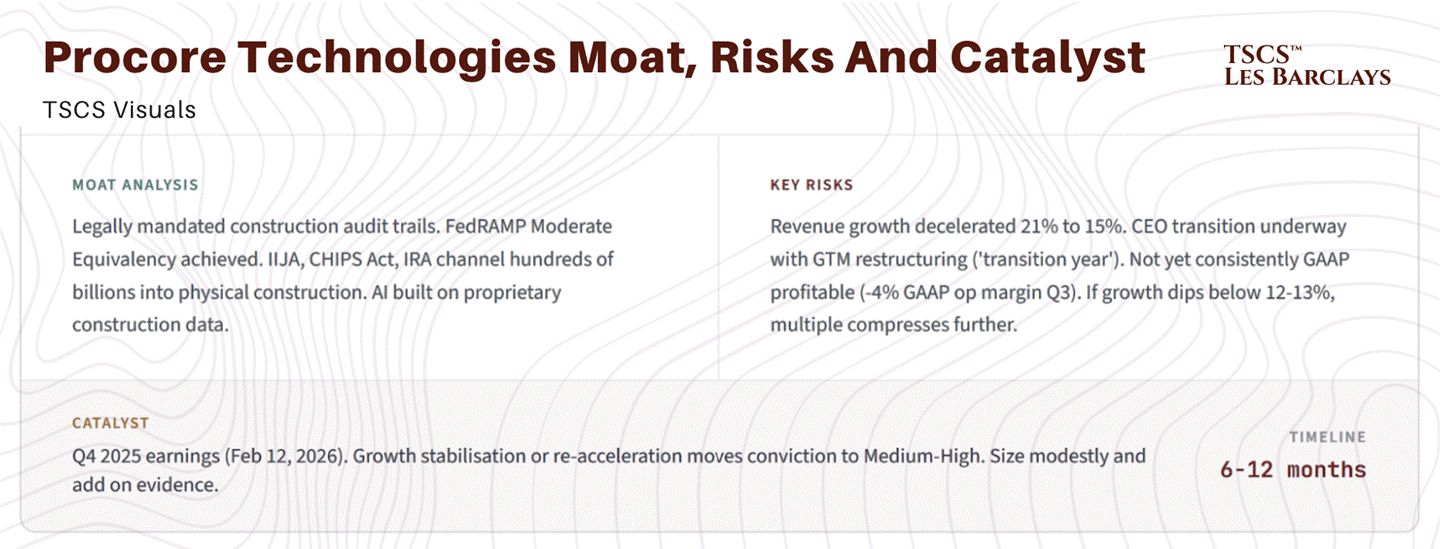

Idea #5: Guidewire Software (GWRE), The Insurance Fortress

Guidewire is the dominant platform for property and casualty insurance core systems globally, and arguably a purer Fortress Zone expression than ServiceNow with a fraction of the sell-side coverage. Its InsuranceSuite runs the operational backbone of insurers: policy administration, claims adjudication, and billing. This is the deterministic system of record that every AI agent in insurance must operate through.

The stock has been halved from its September 2025 highs of $272 to approximately $128-139. At ~9x forward revenue, you are paying mid-single-digit multiples for a company with 22% ARR growth, accelerating cloud migration, record-low attrition, and a regulatory moat that will take any competitor a decade to replicate.

The numbers: ARR of $1.06 billion (Q1 FY2026), up 22% year-over-year, with full-year guidance raised to $1.23 billion. Revenue guided at $1.4-1.42 billion (14-15% growth). Subscription gross margins of 71-72%, improving 4 percentage points year-over-year and targeting 80% long-term. Operating cash flow guided at $350-370 million. Cash position of $1.48 billion. Gross revenue retention at record highs. Cloud ARR growing 36% year-over-year, now 74% of total ARR.

The cloud transition is the key catalyst. Guidewire is mid-cycle converting on-premise insurers to its cloud platform. As each insurer migrates, Guidewire locks in longer contracts (Liberty Mutual signed a ten-year commitment), higher ARR per customer, and improving margins. The transition is still only ~74% complete, providing a significant remaining tailwind. The new CEO, Ajei Gopal (who tripled Ansys revenue and led it to a $35B acquisition by Synopsys), is an execution-focused operator suited to this stage.

Guidewire is also embedding AI through acquisitions (ProNavigator, Quanti) and new products (PricingCenter, UnderwritingCenter), all built on top of its own platform data rather than as standalone products. Think about it: AI deepens the moat rather than threatening it.

The risk: Execution on large-scale cloud migrations. Guidewire’s implementation projects are complex and multi-year. A botched migration at a tier-1 insurer would damage the referenceability that drives new deals. The company is also still expanding margins from a lower base than peers (71% subscription gross margin vs 80%+ for mature SaaS), so the margin expansion narrative needs to continue delivering.

Conviction: Medium-High. Timeline: 12-24 months. The catalyst is continued cloud migration progress and margin expansion toward the 80% target. Each quarter that ARR growth holds above 20% with improving margins narrows the valuation gap to peers.

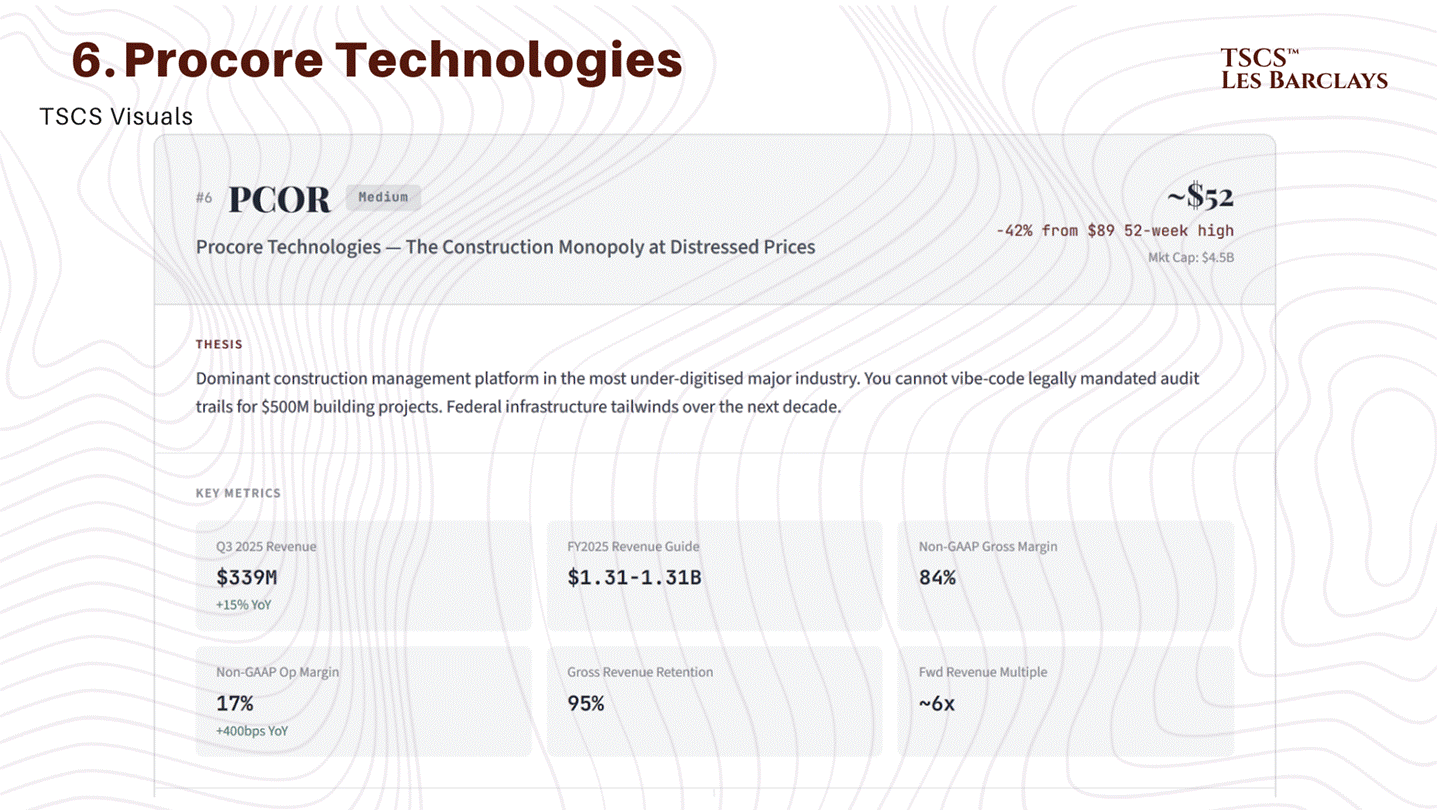

Idea #6: Procore Technologies (PCOR), The Construction Monopoly at Distressed Prices

Procore is the dominant cloud-based construction management platform globally, covering the entire lifecycle from preconstruction through financial management. Construction is the most under-digitised major industry on earth, and the AI disruption narrative falls apart entirely here: you cannot vibe-code a system that tracks legally mandated audit trails for $500 million building projects.

At ~$52 (down 42% from its $89 52-week high), Procore trades at roughly 6x forward revenue. The market is pricing it as if construction management software is about to be disrupted by AI agents. In reality, construction is the one industry where AI adoption will be slowest and where the system of record is most critical.

The numbers: $339 million Q3 2025 revenue, up 15% year-over-year. FY2025 guided at $1.312-1.314 billion. Non-GAAP gross margin of 84%. Non-GAAP operating margin of 17%, expanding 400 bps year-over-year. Gross revenue retention of 95%. Free cash flow of $68 million in Q3, up 194% year-over-year. $300 million share repurchase programme authorised November 2025. FedRAMP “Moderate Equivalency” achieved in Q3 2025, opening US federal construction projects.

Procore is deploying AI through Procore Assist and Procore Agent Builder, both built on its proprietary construction data. An AI model cannot adjudicate a construction change order without access to the project documentation, budget history, and contractual terms that live inside Procore. The sector itself is a tailwind: the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, CHIPS Act, and Inflation Reduction Act channel hundreds of billions into physical construction over the next decade. Barclays upgraded Procore to Overweight in January 2026 on this basis.

The risk: Revenue growth has decelerated from 21% to 15%, and the company is undergoing a CEO transition (Courtemanche to Gopal) with GTM restructuring that management has called a “transition year.” If the transition slows growth further (below 12-13%), the multiple compresses. Procore is not yet consistently GAAP profitable (GAAP operating margin was -4% in Q3 2025), though it is rapidly approaching the inflection point.

Conviction: Medium. Timeline: 6-12 months, with a hard catalyst on February 12, 2026 (Q4 2025 earnings). If results show growth stabilisation or re-acceleration, conviction moves to Medium-High. This is a name to size modestly and add on evidence.

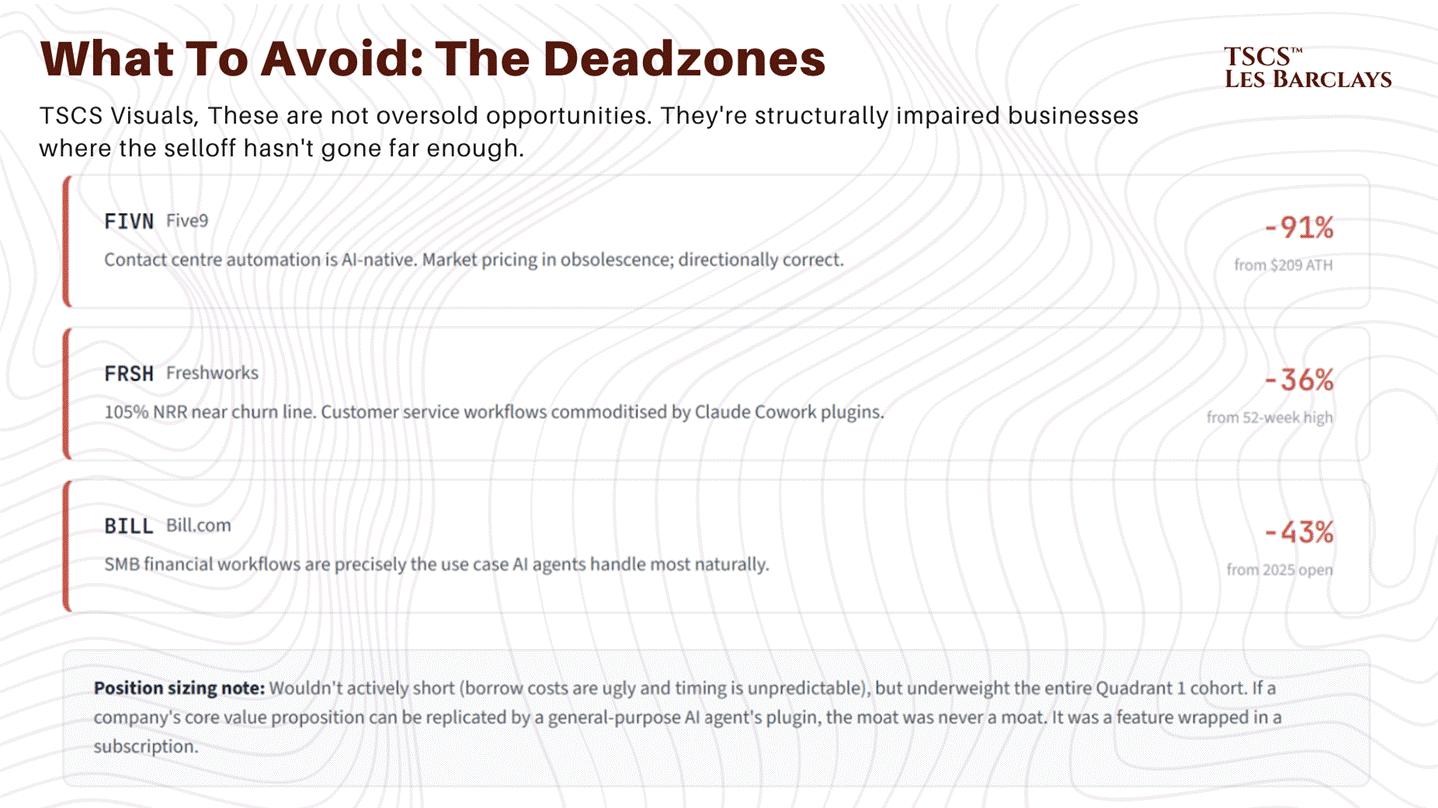

What to Avoid: The Dead Zone Shorts

For completeness, and because I believe in symmetry: the Dead Zone names are not “oversold opportunities.” They’re structurally impaired businesses where the selloff hasn’t gone far enough.

Five9 at $18 (down from $209) is pricing in obsolescence, and I think the market is directionally correct. Freshworks at 105% NRR with commoditised customer service workflows faces a world where Claude Cowork plugins do 80% of what their platform does at near-zero marginal cost. Bill.com, down 43% in 2025, processes SMB financial workflows that are precisely the use case that AI agents handle most naturally.

I wouldn’t actively short these (the borrow costs are ugly and the timing is unpredictable), but I’d underweight the entire Quadrant 1 cohort. The risk/reward on the long side of Dead Zone names is atrocious. You’re catching knives with no gloves.

Section 7: Risk Factors and What Breaks the Thesis

I’ve built a deliberately contrarian case. Now let me tell you exactly what would make me wrong. Any analyst who doesn’t do this is either overconfident or intellectually dishonest, and I’m trying to be neither.

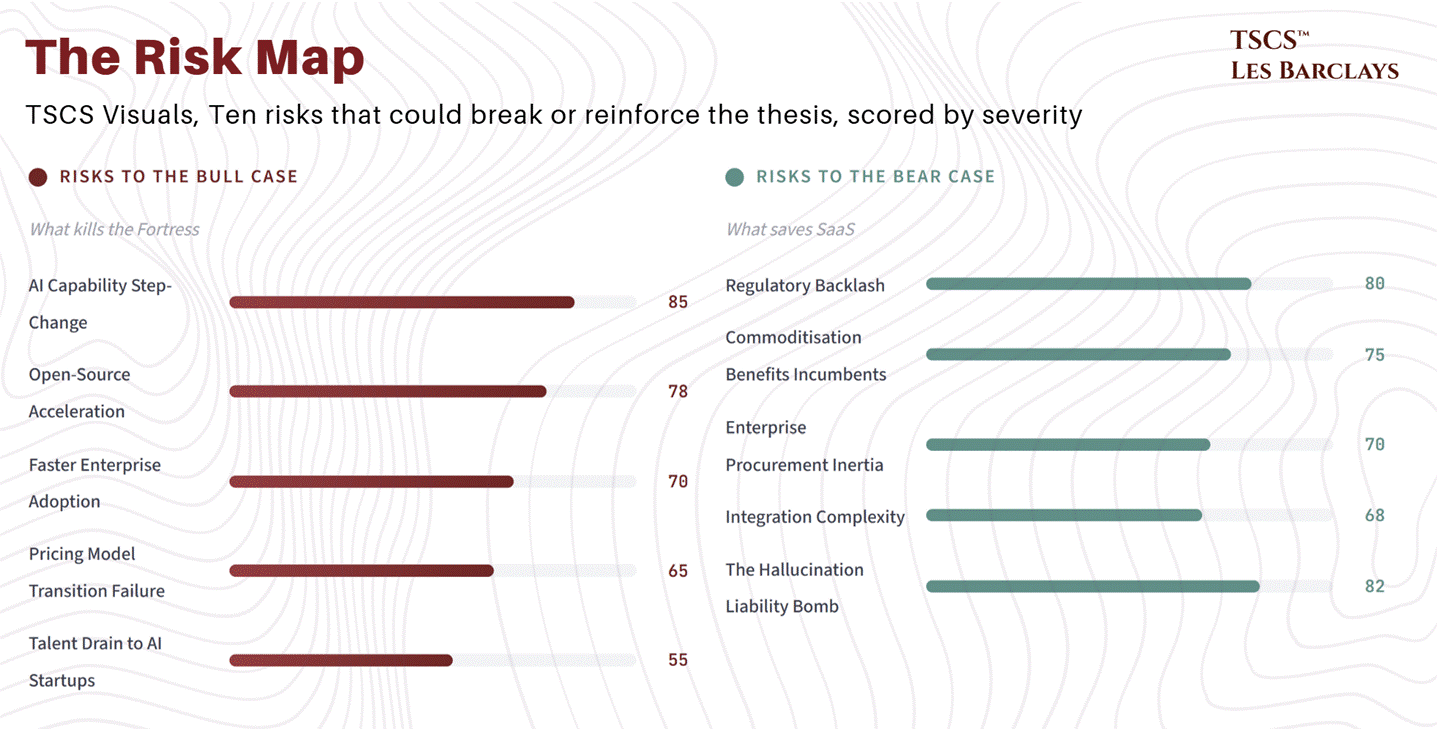

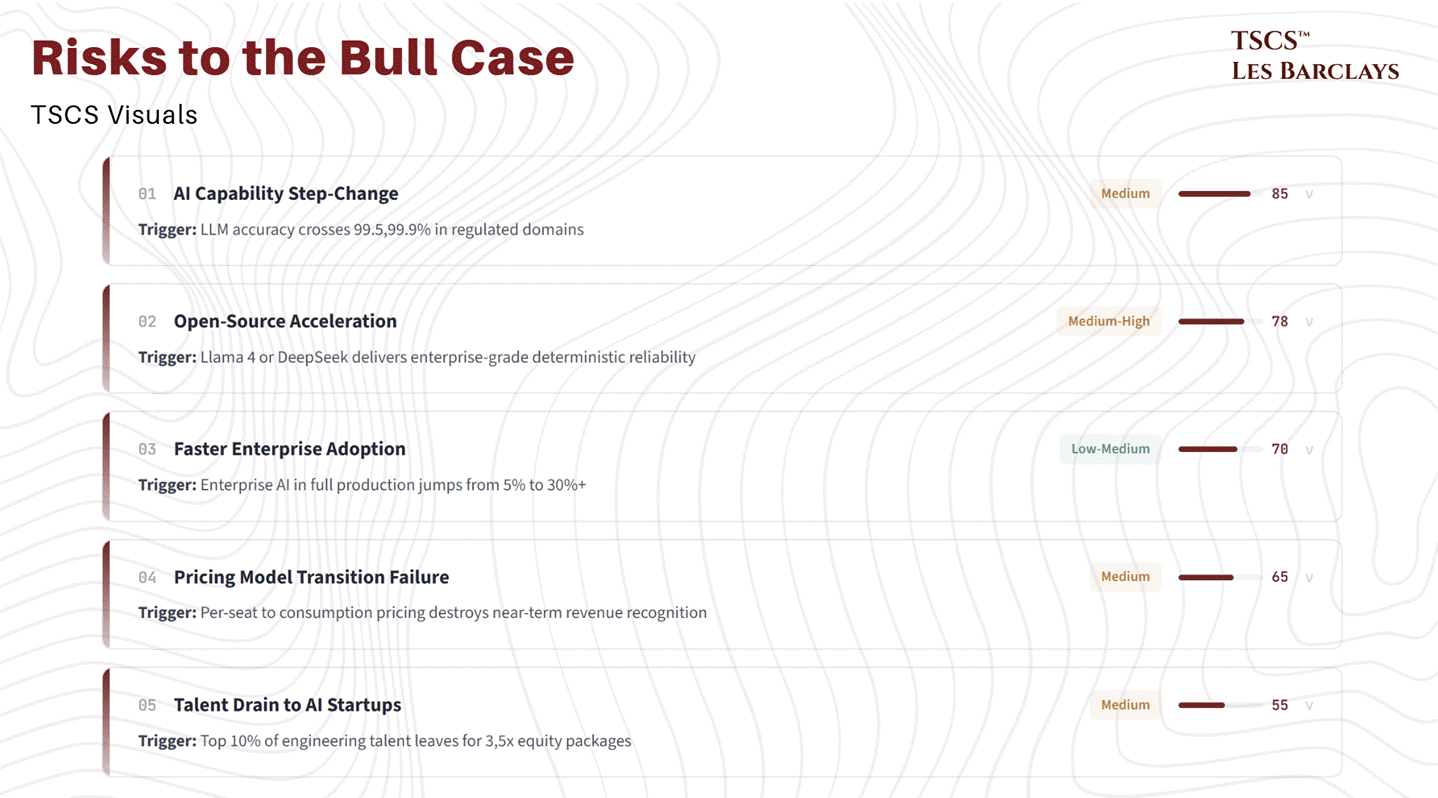

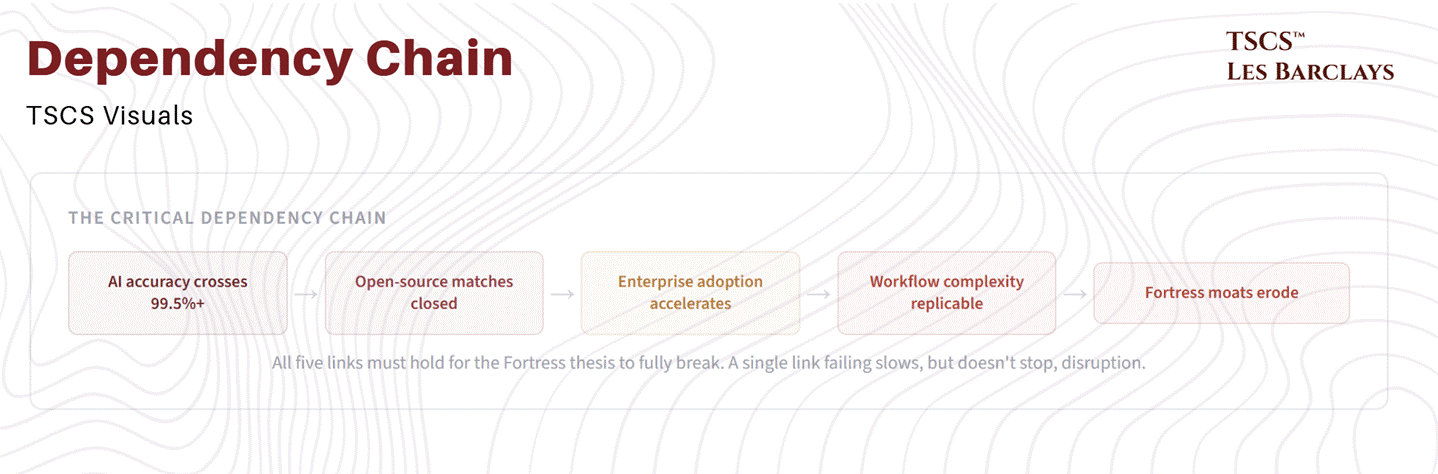

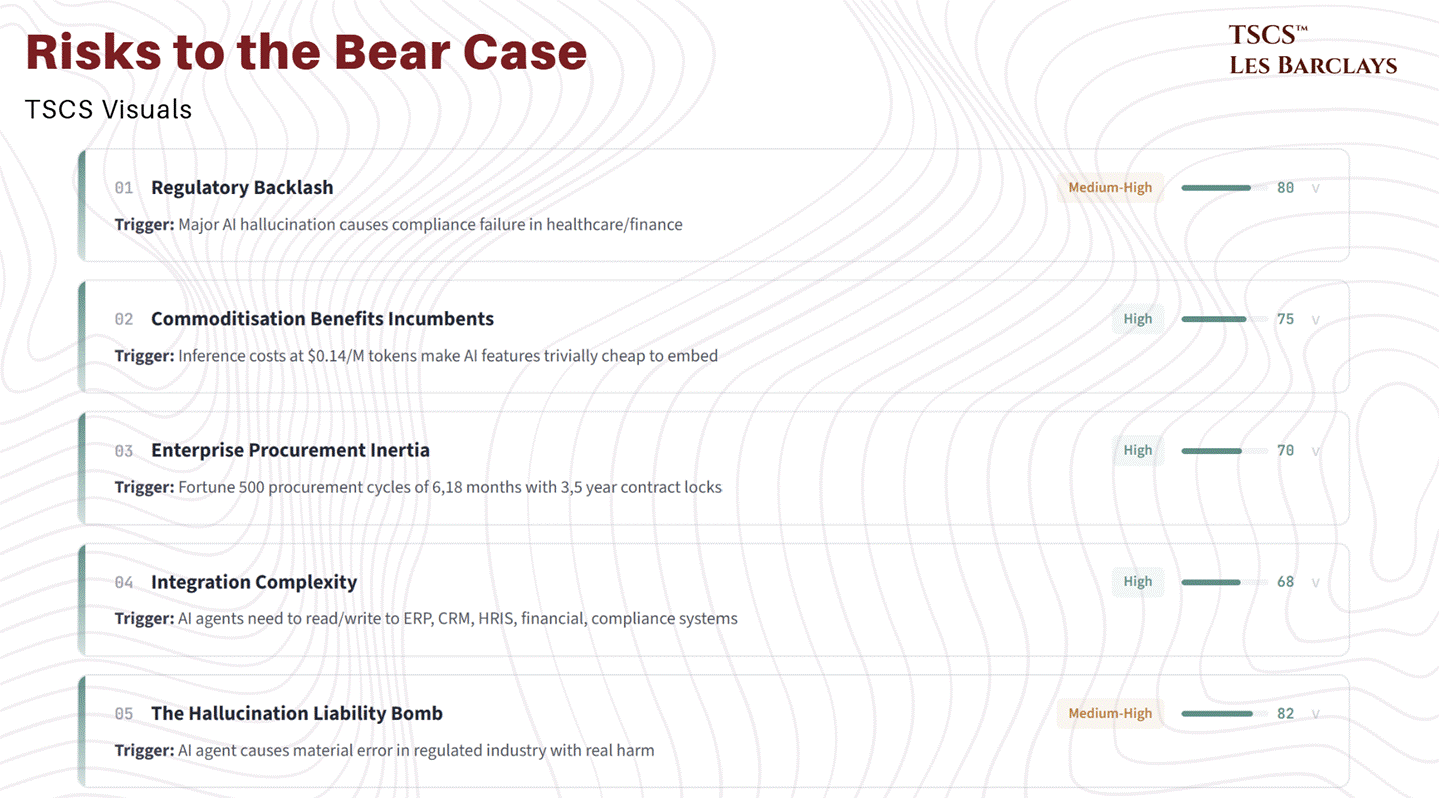

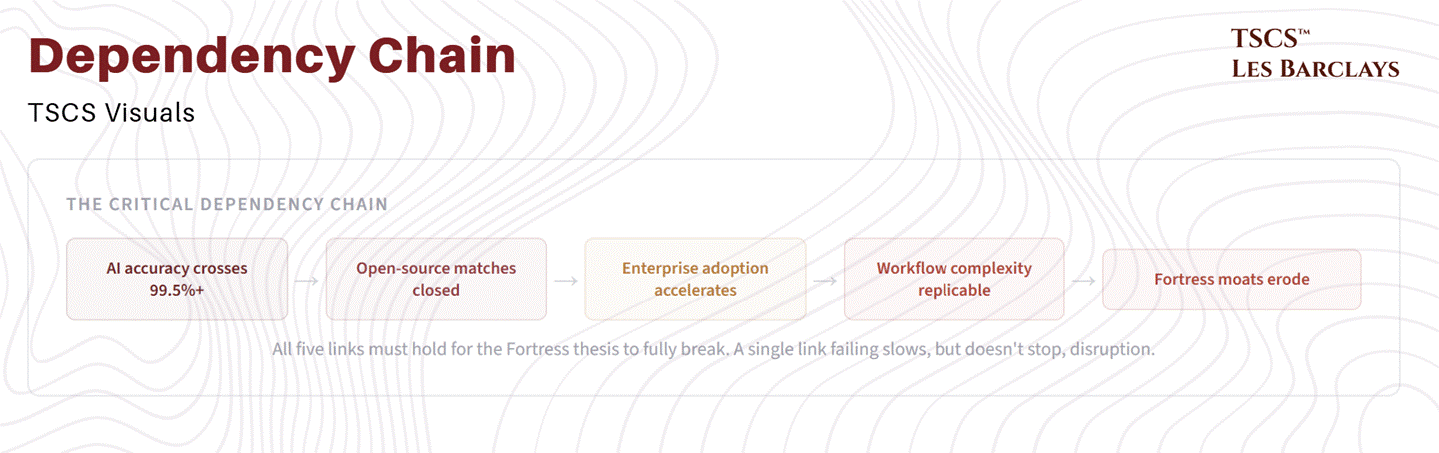

7A: Risks to the Bull Case (What Kills the Fortress)