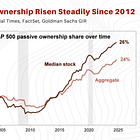

40 Equities That Control AI Infrastructure

From Memory Yields to Grid Transformers, a second part

“Information is physical.”

— Rolf Landauer, IBM Research

Last week, we showed you where the money flows: the generators, the cooling units, the switchgear, the fiber. The physical layer that turns “cloud computing” from marketing fiction into concrete reality.

This week, we show you where the money compounds.

Part 1 was logistics. Part 2 is leverage.

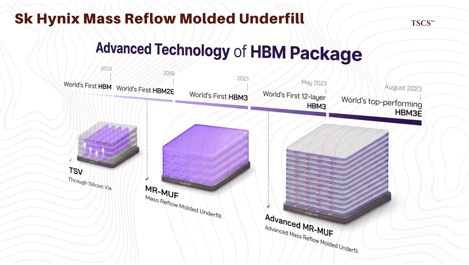

We are now ascending the stack, from the electrons that power the facility to the photons that carry the data, from the memory architectures that feed the GPUs to the custom silicon that threatens Nvidia’s monopoly. This is where the margin structures get interesting, where process engineering creates decade-long moats, and where a single packaging technique (MR-MUF vs. TC-NCF) determines whether a memory company trades at 8x or 18x earnings.

The average investor sees “AI infrastructure” as a monolith. The professional sees it as a series of chokepoints, each with its own physics, its own lead times, and its own competitive dynamics.

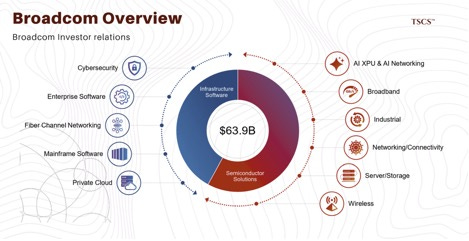

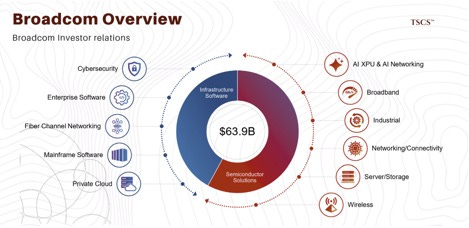

SK Hynix’s 62% HBM market share is not luck. It is a specific underfill process that Samsung failed to master. Broadcom’s networking dominance is not brand recognition. It is the fact that 80-90% of high-speed data center traffic passes through their Tomahawk silicon. Cleveland-Cliffs’ domestic monopoly on electrical steel is not scale. It is regulatory protection and 150-week transformer lead times.

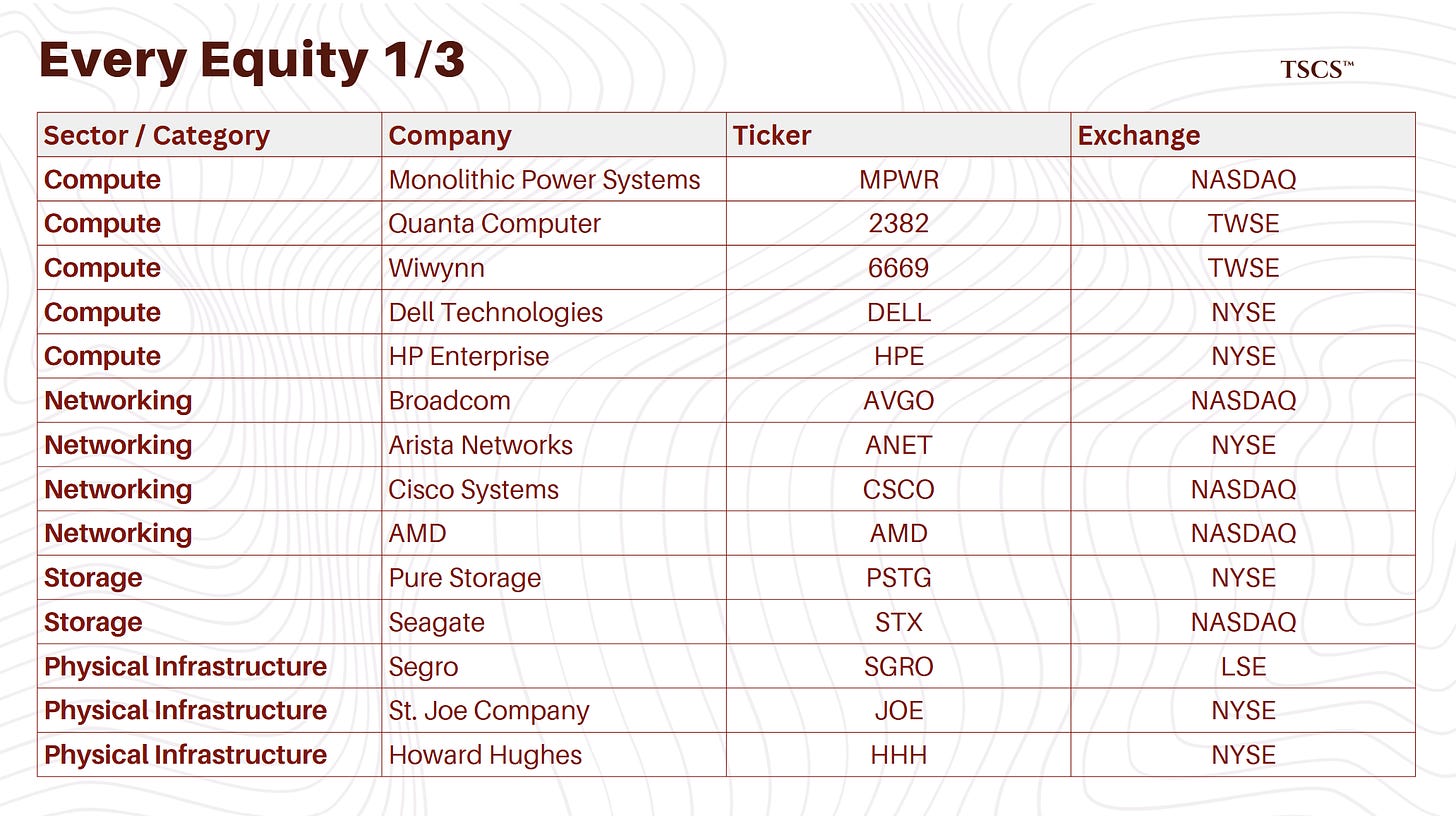

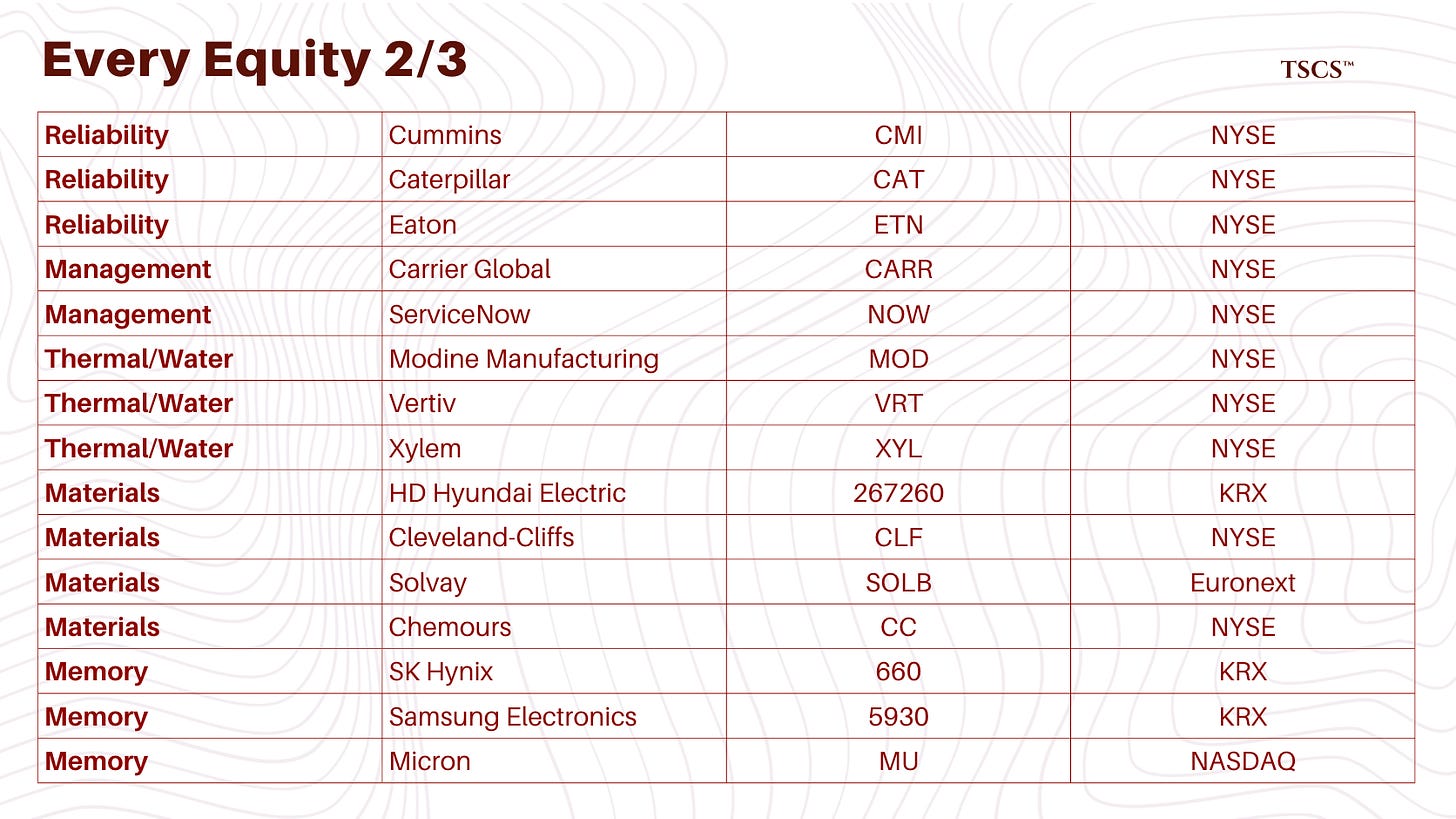

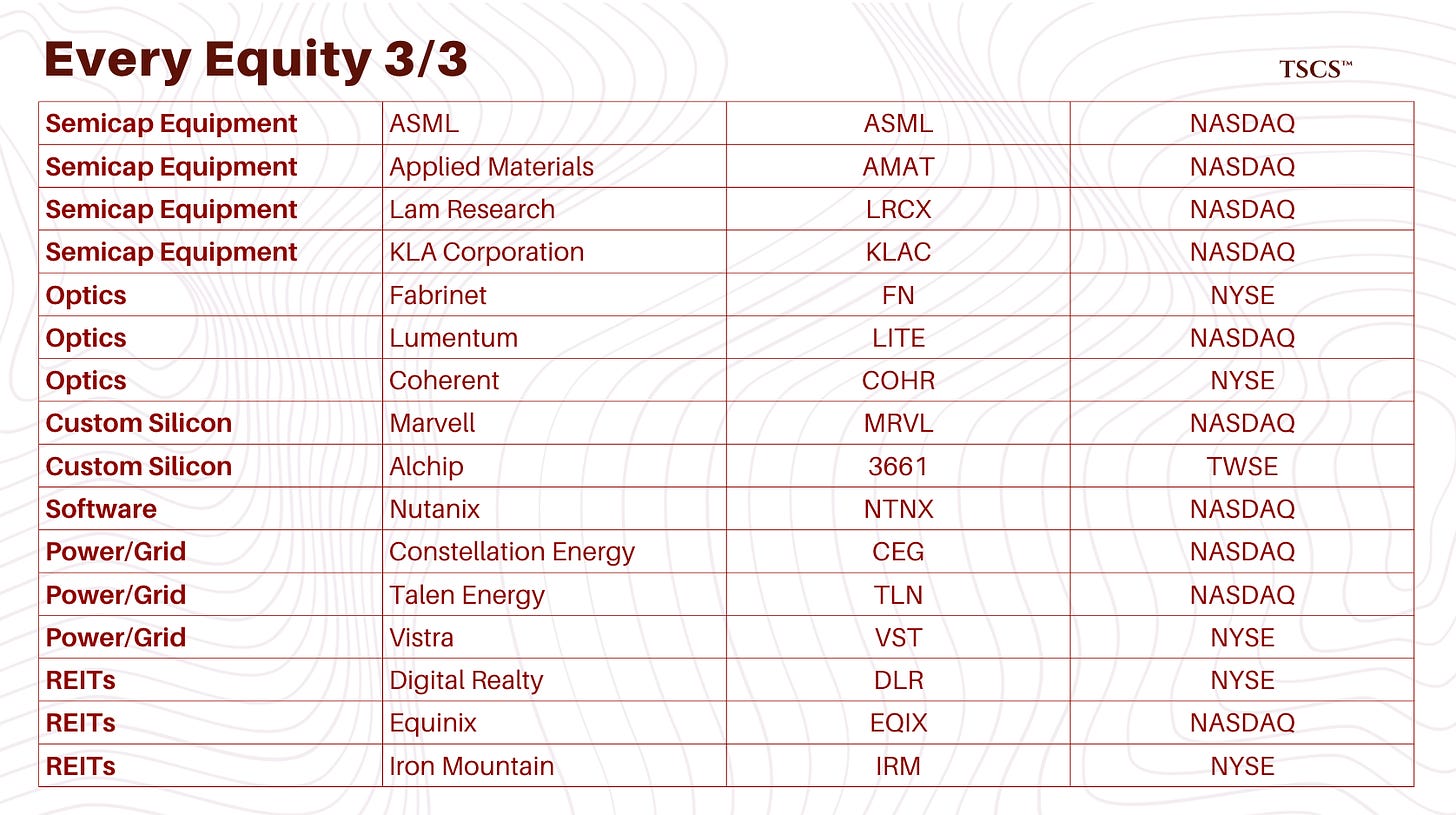

This 60+ page analysis maps the complete upper stack:

What Part 2 Covers:

Compute: The death of blade servers, the rise of rack-scale architecture, and why Taiwanese ODMs (Quanta, Wiwynn) are eating Dell and HPE alive in the hyperscale market

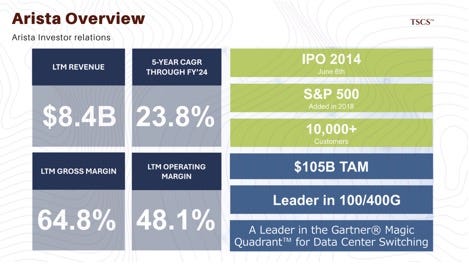

Networking: The InfiniBand vs. Ultra Ethernet war, Broadcom’s 80-90% switching monopoly, and Arista’s $3.7 billion free cash flow explosion

Storage: Pure Storage’s DirectFlash physics advantage, Seagate’s HAMR defense, and why HDDs cannot live near GPUs

Physical Infrastructure: The 150-week transformer bottleneck, land banking as the new gold rush, and why air cooling is dead for AI

Software: The VMware exodus and who captures the refugees (Nutanix, Red Hat)

Reliability: Why Cummins wins on transient response, why diesel beats natural gas, and Eaton’s single point of failure problem

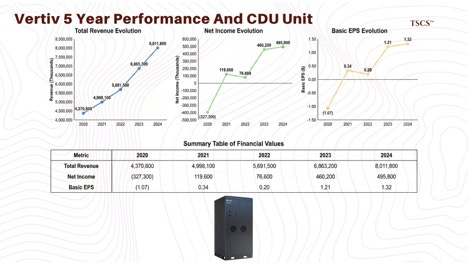

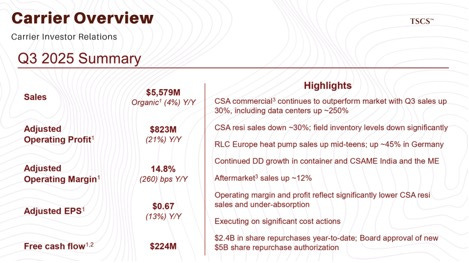

Thermal Management: Carrier’s DCIM play, Modine’s predictive cooling AI, Vertiv’s water-free future, and Xylem’s 5-micron filtration moat

Critical Materials: The transformer oligopoly (HD Hyundai, Hitachi, Siemens), Cleveland-Cliffs’ GOES monopoly, and the Solvay vs. Chemours immersion cooling battle

Memory: SK Hynix’s MR-MUF process alpha, Samsung’s TC-NCF disaster, Micron’s efficiency weapon, and why HBM4 flattens the playing field

Semiconductor Equipment: ASML’s absolute monopoly, and the Applied/Lam/KLA oligopoly that sits upstream of everything

Optics: Fabrinet’s sole-source erosion, the Lumentum vs. Coherent duopoly, and why Co-Packaged Optics threatens the entire transceiver supply chain

Custom Silicon: Broadcom’s $150 billion OpenAI opportunity, Alchip’s AWS proxy status, and Marvell’s customer concentration risk

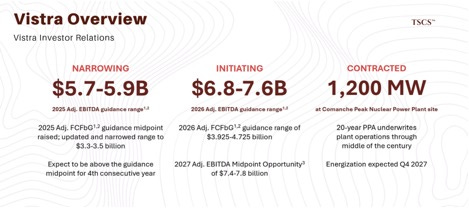

Power & Grid: The nuclear co-location thesis (and FERC’s rejection of it), why Vistra and Constellation win either way, and Iron Mountain’s surprise data center pivot

Why You Need to Be Reading TSCS

At TSCS, we have made it our mission to uncover hidden opportunities before the crowd. Our community is built for investors who want an edge: institutional-grade analysis, creative frameworks, and a proven record of outperformance.

This is not just research. It is a blueprint for compounding wealth with conviction.

In recent months, we have published sector deep-dives such as:

We also provide ruthless stock-specific analyses, highlighting hidden moats and catalysts the market has barely begun to price:

For our paid subscribers:

We will be releasing full deep-dive analyses on select companies from this roadmap, with price targets, risk frameworks, and position sizing guidance.

The “AI Trade” of 2026 is not about buying GPUs. It is about buying the heat sink, the photon, the electron, and the transformer lead time that makes the chip possible.

The market prices narrative. We price physics.

Subscribe now. The bottlenecks are not waiting.

Section 1: Compute - Rack-Scale Architecture and Thermal

The introduction of Nvidia’s Blackwell architecture, specifically the GB200 NVL72, has forced a re-architecture of the data center that privileges manufacturers capable of high-complexity, liquid-cooled integration over traditional “box movers.”

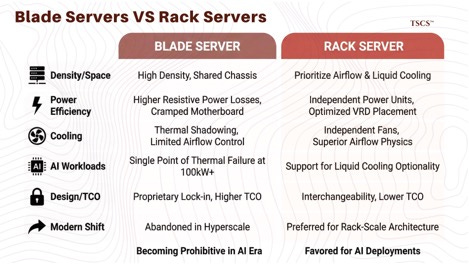

1.1 Decline of the Blade Server

To understand the present, we must analyze the failure of the past. For nearly two decades, the industry debated the merits of “blade servers” versus “rack-mount” servers. Blade servers offered higher density by sharing power and cooling modules across a chassis. However, this density came at a cost that has become basically impossible with AI compute.

First, blade systems suffer from “thermal shadowing” and limited airflow control compared to rack servers, which have independent fans and power units.

In the context of AI workloads, where thermal envelopes are pushed to the physical limit (100kW+ per rack), the shared backplane of a blade chassis becomes a single point of thermal failure.

Second, the miniaturization required for blades leads to higher resistive power losses. Distributing power to dense components on a cramped blade motherboard forces compromises in voltage regulator design (VRDs). Since blade motherboards have less real estate to place VRDs right next to the CPU socket compared to rack equivalents, they incur greater efficiency losses, wasted energy that must then be removed as heat.

The beneficiary of this power delivery complexity is Monolithic Power Systems (MPWR), which dominates the AI server voltage regulator market with 40%+ revenue growth.

Also you should know that blade servers introduce proprietary lock-in. A blade chassis from HPE or Dell typically requires proprietary power supplies and management modules that do not interoperate, increasing the total cost of ownership (TCO) for hyperscalers who demand interchangeability.

As a result, the blade form factor is largely being abandoned in hyperscale AI deployments in favor of “rack-scale” architectures that prioritize airflow physics and liquid cooling optionality over mere physical compactness.

1.2 NVL72 and Liquid Cooling Rise

Nvidia’s GB200 NVL72 serves as the new replacement. It functions as a singular exascale computer connected by a copper backplane (NVLink) that acts as a unified fabric.

This design represents a step-function change in manufacturing complexity.

The NVL72 requires a liquid cooling infrastructure that traditional enterprise data centers lack. The system demands precise coolant distribution units (CDUs) and manifolds to manage the thermal load of 72 Blackwell GPUs and Grace CPUs running in unison.

This shifts the value add from “assembly” to “thermal engineering.” Manufacturers must now possess advanced capabilities in fluid dynamics to ensure leak-proof, high-pressure coolant delivery.

1.3 ODM Direct Model - Quanta & Wiwynn

The primary beneficiaries of this architectural shift are the Taiwanese Original Design Manufacturers (ODMs): Quanta Computer (QCT) and Wiwynn. Historically, these firms operated in the shadows, manufacturing white-label boxes for Dell or HPE. Today, they effectively bypass the branded middlemen to sell directly to the hyperscalers (”ODM Direct”).

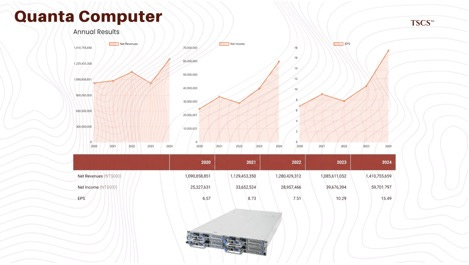

Quanta Computer: Quanta has cemented itself as a critical partner for the “Big 4” (Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Meta). Reports indicate Quanta is a lead integrator for the GB200 NVL72 systems, leveraging its long history of rack-level integration. Their ability to deliver “rack-level” solutions (where the product leaving the factory is a fully tested, liquid-cooled rack rather than a pallet of servers) aligns perfectly with the hyperscalers’ need for deployment velocity. Quanta’s revenue is increasingly driven by these massive, custom AI server projects, which now dwarf traditional enterprise sales.

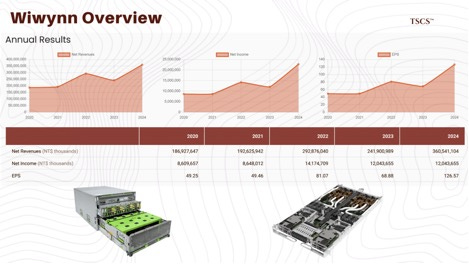

Wiwynn: Spun off from Wistron, Wiwynn has deeply integrated itself with Microsoft and Meta, focusing heavily on Open Compute Project (OCP) standards. Wiwynn’s revenue exposure is heavily weighted toward these hyperscalers, making them a pure-play derivative of the capex cycle. They have showcased specific readiness for the GB200 NVL72, developing proprietary coolant distribution units (CDUs) and “blind-mate” quick disconnects to manage the liquid cooling requirements. Furthermore, Wiwynn contributes significantly to OCP designs like the “Grand Teton” server platform used by Meta, reinforcing their status as a co-designer rather than just a manufacturer.

This ODM dominance is quantified in the market data: In Q4 2024, nearly 47.3% of global server revenue was attributed to ODM Direct sales, a segment that now eclipses any single brand like Dell or HPE (research by IDC).

1.4 The Traditional OEM Dilemma (Dell & HPE)

While Dell and HPE remain titans in the enterprise market, their share of the AI hyperscale buildout is under structural pressure from the ODM Direct model. The hyperscalers, who account for the vast majority of AI spending, have little need for the support, warranty, and management software layers that justify OEM margins.

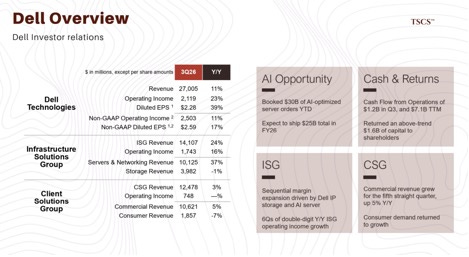

However, the “AI Sovereign Cloud” and enterprise private AI markets offer them a new chance. Dell and HPE are positioning themselves as the necessary partners for Fortune 500 companies and governments that lack the engineering resources to integrate ODM racks directly. Dell’s recent financial results underscore this bifurcation: their Infrastructure Solutions Group (ISG) reported record revenue of $16.8 billion, up 44% year-over-year, driven almost entirely by AI servers. Yet, the margins in this segment are dilutive compared to their traditional storage and core server businesses.

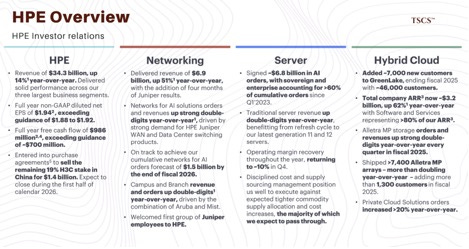

HPE is pivoting aggressively to escape this commoditization trap. Their acquisition of Juniper Networks signals a strategic shift toward high-margin networking and hybrid cloud management. By bundling AI compute with high-performance networking fabric, HPE attempts to recreate the proprietary moat that the “white box” server market eroded.

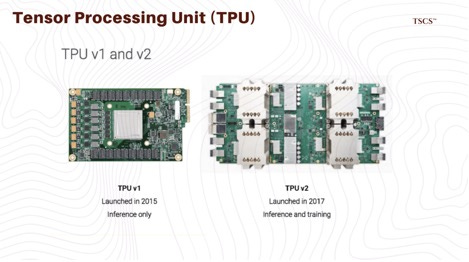

1.5 Custom Silicon Layer - Google TPU

It is crucial to note that the Nvidia monopoly is not absolute. Google has its own way using the Tensor Processing Unit (TPU). Unlike other hyperscalers who are largely dependent on Nvidia’s roadmap, Google designs its TPUs in-house for its specific AI workloads, such as the Gemini models.

While Google designs the chip, they rely on partners for the physical infrastructure. Broadcom plays a critical but often understated role here, assisting with the custom ASIC design and SerDes (serializer/deserializer) IP that allows TPUs to communicate. The manufacturing of the TPU server racks is then handled by ODMs like Inventec and Quanta, further reinforcing the “ODM Direct” thesis even within the custom silicon ecosystem. This vertical integration allows Google to optimize its cost structure and reduce dependency on the tight supply of Nvidia GPUs, although they remain a significant buyer of H100/Blackwell chips for their Cloud customers who demand the Nvidia software stack (CUDA).

AMD’s MI300X has gained traction with hyperscalers seeking Nvidia alternatives, though CUDA’s software moat and Nvidia’s different approach to total-system design (NVLink fabric, DGX integration) maintain the competitive gap.

Section 2: Networking

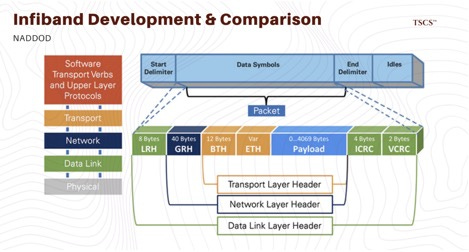

2.1 The Incumbent - InfiniBand

Historically, InfiniBand (controlled by Nvidia via its Mellanox acquisition) has been the gold standard for high-performance computing (HPC) and AI training. Its dominance comes from its ability to provide a “lossless” network fabric.

In an InfiniBand network, data is transferred directly between the memory banks of servers via Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA), a protocol that allows one server to read or write another server’s memory without involving either CPU. This bypass eliminates the overhead of the operating system’s network stack, reducing latency to the microsecond level.

InfiniBand’s credit-based flow control ensures that a transmitter never sends a packet unless the receiver has the buffer space to accept it. This prevents packet loss and the subsequent re-transmission delays that kill AI training performance. For tightly coupled workloads like training a massive Large Language Model (LLM) across thousands of GPUs, InfiniBand has been the default choice due to this predictability and low tail latency.

2.2 Challenger - Ultra Ethernet Consortium (UEC)

However, the industry is rebelling against Nvidia’s end-to-end dominance. The Ultra Ethernet Consortium (UEC), a powerful coalition including Broadcom, Arista, Cisco, AMD, Meta, and Microsoft, is re-engineering Ethernet to match InfiniBand’s performance while maintaining Ethernet’s open standards, multi-vendor ecosystem, and cost advantages.

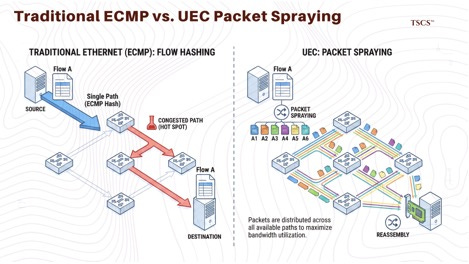

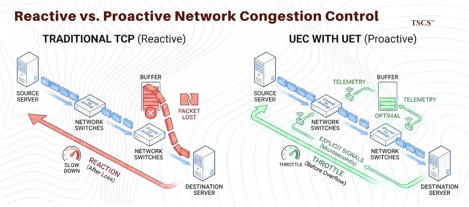

The UEC is introducing critical innovations to the Ethernet stack to address its historical shortcomings in AI workloads:

● Packet Spraying: Traditional Ethernet (via ECMP) relies on flow hashing, which sends all packets of a specific “flow” down a single path to maintain order. If that path becomes congested, the entire flow suffers. UEC introduces “packet spraying,” which breaks a flow into individual packets and sprays them across all available paths in the network simultaneously. The destination Network Interface Card (NIC) is responsible for reassembling them. This maximizes bandwidth utilization across the spine-leaf topology and eliminates “hot spots.”

● Telemetry-Driven Congestion Control: UEC implements advanced telemetry that allows the network to react to congestion in microseconds. Unlike traditional TCP, which only reacts after a packet is lost (too late for AI), UEC’s transport protocol (UET) uses explicit signals to throttle traffic before buffers overflow, mimicking the lossless behavior of InfiniBand without the proprietary lock-in.

2.3 Broadcom

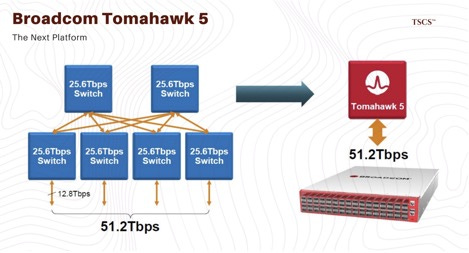

While Nvidia captures the headlines, Broadcom effectively owns the market for merchant switching silicon, the chips that power the switches connecting these racks. Their Tomahawk 5 switch ASIC is the de facto standard for high-performance AI networks, boasting a switching capacity of 51.2 Terabits per second (Tbps).

The Tomahawk 5 is critical because it enables the “radix” (port count) necessary to flatten network topologies. A single Tomahawk 5 chip supports 64 ports of 800GbE, allowing network architects to build massive, flat networks with fewer layers of switches (hops). This reduces latency and power consumption, Broadcom claims a single Tomahawk 5 can replace 48 older Tomahawk 1 switches, reducing power consumption by 95%.

With an estimated 80-90% market share in high-speed data center switching, Broadcom acts as a “toll booth” operator on AI traffic. Every time data moves between GPUs in a non-InfiniBand cluster (which is the majority of the hyperscale market outside of pure Nvidia SuperPODs), it almost certainly passes through a Broadcom chip.

2.4 Switch Vendors - Arista Networks vs. Cisco

The battle for the box that houses these chips is primarily between Arista Networks and Cisco.

Arista Networks (ANET): Arista has capitalized masterfully on the shift to high-speed Ethernet. Their EOS operating system is built from the ground up for the programmability, telemetry, and open standards required by hyperscalers. Arista is the primary vehicle for the UEC standard and is actively deploying 800G switches based on Broadcom’s Tomahawk 5 silicon. Financial data shows Arista’s free cash flow exploding to $3.7 billion in 2024, an 83% increase, reflecting their dominance in the AI back-end network.

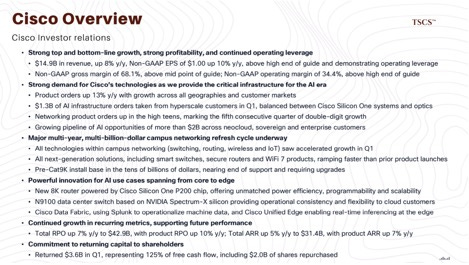

Cisco Systems (CSCO): By comparison, Cisco retains a massive footprint in enterprise campus and office networking but has struggled to penetrate the hyperscale AI backend to the same degree. While they have introduced 800G Nexus switches and their own Silicon One ASICs, their historical reliance on proprietary, closed architectures has been a friction point for cloud giants who prefer the disaggregated model. However, Cisco is attempting to pivot by joining the UEC and embracing the open Ethernet standards, acknowledging that the future of AI networking cannot be a walled garden.

Section 3: Storage (Density & Physics)

AI models do not just require compute; they require massive datasets fed into memory at high speed. This has reignited innovation in the storage layer, driving a wedge between traditional Hard Disk Drives (HDDs) and All-Flash Arrays (AFAs). The battle is no longer just about cost per gigabyte, but about density, power efficiency per terabyte, and the physics of media reliability.

3.1 Pure Storage and DirectFlash Advantage

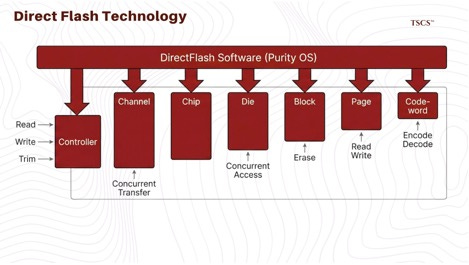

Pure Storage (PSTG) has emerged as a disruptive force against traditional SSD vendors (like Samsung or Micron) and storage array providers (NetApp, Dell). Their competitive advantage lies in their proprietary DirectFlash technology.

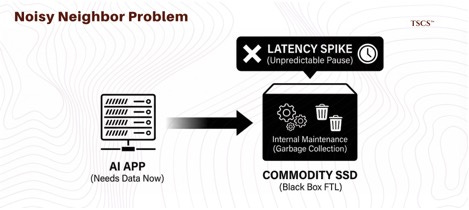

In a standard commodity SSD, a controller inside the drive manages data placement, wear leveling, and “garbage collection” (erasing old data to make room for new). This architecture creates a “Flash Translation Layer” (FTL) that acts as a black box; the central storage operating system doesn’t know what the drive is doing. This leads to the “noisy neighbor” problem where a drive might pause for internal maintenance right when the AI application needs data, causing unpredictable latency spikes.

Pure Storage removes the controller from the drive module entirely. Their DirectFlash Module (DFM) is essentially raw NAND flash connected directly to the system. Pure’s software (Purity OS) manages the flash globally across the entire array.

Physics-Level Implications:

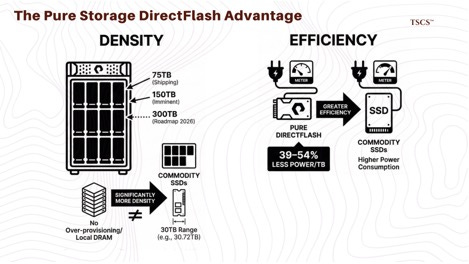

● Density: Because they don’t need over-provisioning and local DRAM on every single drive, Pure can pack significantly more density into a standard footprint. They are currently shipping 75TB modules, with 150TB modules shipping imminently and a roadmap to 300TB by 2026. In comparison, standard commodity SSDs are largely stuck in the 30TB range (e.g., 30.72TB drives).

● Efficiency: DirectFlash drives typically consume 39–54% less power per terabyte than competitors because they eliminate the redundant processing power of thousands of individual SSD controllers (ARMs) sitting idle on every drive.

● Hyperscale Adoption: This efficiency advantage has caught the eye of the hyperscalers. Meta has publicly stated they are collaborating with Pure Storage to integrate these high-density modules into their storage hierarchy, validating the technology for the most demanding environments on earth.

3.2 Seagate and the HAMR Resistance

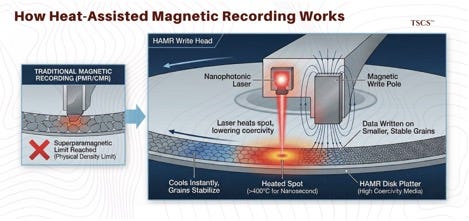

Despite the flash revolution, HDDs remain the only economically viable medium for exabyte-scale bulk storage. Seagate is defending this territory with Heat-Assisted Magnetic Recording (HAMR), which uses a nanophotonic laser to heat a tiny spot on the platter to over 400°C for a nanosecond, allowing data to be written on smaller, more stable magnetic grains.

Seagate is shipping 30TB+ drives on the Mozaic 3+ platform, with roadmaps to 50TB and 100TB. For “warm” or “cold” data not accessed continuously, HDDs offer cost-per-bit that flash cannot match.

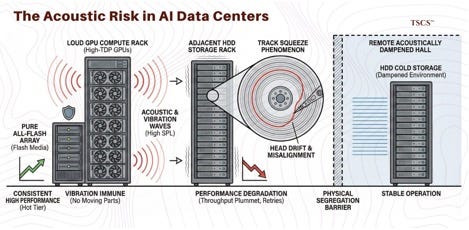

The constraint is acoustic. High-density GPU racks generate immense sound pressure and vibration from cooling fans. HDD performance degrades in high-vibration environments due to “track squeeze,” where the read/write head drifts off nanometer-scale data tracks. This forces physical segregation: HDDs in acoustically dampened halls, far from GPU compute rows. The bifurcation reinforces the value of All-Flash Arrays for the “hot” tier close to compute, as flash is immune to vibration.

Section 4: Physical Infrastructure: Power, Cooling, and Real Assets

The most acute bottlenecks in the AI value chain are no longer silicon, but atoms: copper, steel, water, and dirt. The constraints have shifted from the chip fab to the utility substation.

4.1 The Transformer Bottleneck & Power Scarcity

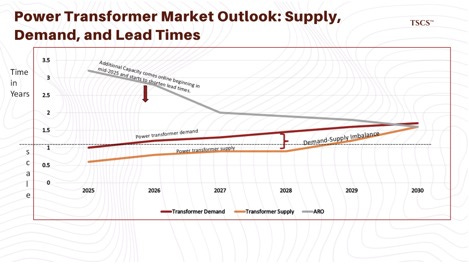

The lead time for large substation power transformers, the massive units that step down voltage from the transmission grid to the facility, has exploded from roughly 50 weeks in 2021 to 120–210 weeks in 2025. This single component is delaying data center energization by years. Domestic manufacturing capacity is maxed out, and labor shortages in specialized electrical engineering are exacerbating the crisis.

Utilities are reacting defensively to this insatiable demand. Dominion Energy, the monopoly provider for Northern Virginia (the world’s data center capital), has implemented the GS-5 rate schedule. This new framework forces large data center customers (with demand >25MW) to pay for a minimum of 85% of their contracted distribution demand and 60% of generation demand, regardless of whether they actually use it. This effectively shifts the financial risk of stranded assets from the ratepayer to the data center operator, raising the barrier to entry for smaller players and favoring the well-capitalized hyperscalers.

4.2 Land Banking: The New Gold Rush

With power availability becoming the primary constraint, real estate developers who possess “powered land”, sites with secured grid connections and permits, are sitting on appreciating gold mines.

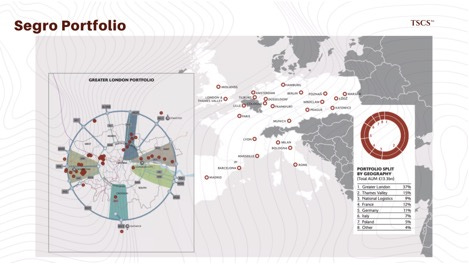

Segro (Europe): Segro has quietly amassed a “power bank” of 2.3 GW across Europe’s key availability zones (Slough, London, Frankfurt, Paris). They are pivoting their strategy from merely leasing powered shells to building fully fitted data centers via Joint Ventures (e.g., with Pure Data Centres Group). By moving up the stack, they aim to capture higher yields (targeting 9-10% yield on cost) compared to traditional logistics warehousing. Their dominance in Slough, a critical hub for London’s internet traffic, gives them immense pricing power.

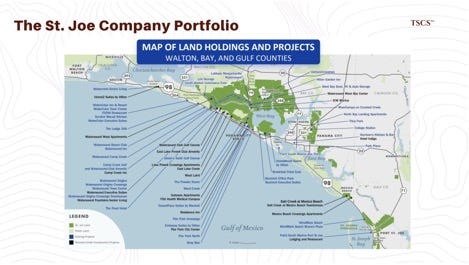

The St. Joe Company (Florida): St. Joe holds a unique position with over 170,000 acres of land in the Florida Panhandle. While not a traditional data center hub, their massive contiguous land holdings and access to energy infrastructure position them well for edge compute and subsea cable landing stations. Their land bank includes over 110,000 acres in the Bay-Walton Sector Plan alone, providing a generational runway for development.

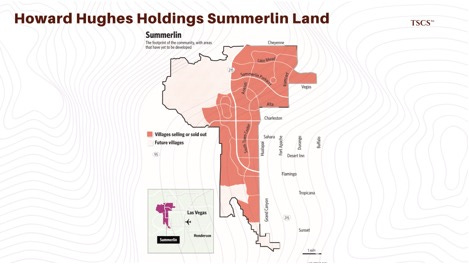

Howard Hughes Holdings (Nevada): Controlling vast tracts of land in master-planned communities like Summerlin, HHH sits on valuable dirt. However, their strategy has been mixed. They recently sold a 240-acre parcel (”Back Bowl”) for ~$100 million rather than developing it themselves, potentially missing the recurring revenue opportunity of data center leasing.

4.3 Cooling: The Phase Change

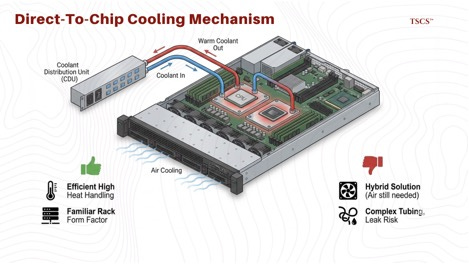

Air cooling is dead for the AI tier. With rack densities approaching 120kW for Blackwell Ultra, traditional HVAC cannot remove heat fast enough. The industry is moving toward Direct-to-Chip (DLC) liquid cooling, where cold plates sit directly on the GPUs (as seen in the GB200 NVL72), with coolant distributed via manifolds.

This introduces new operational risks: leaks, fluid chemistry maintenance, and massive weight loads on raised floors. It also benefits specialized component suppliers. Vertiv and other thermal management firms are critical partners, as are the ODMs like Wiwynn who have developed proprietary CDUs to plumb these systems without creating a water hazard in the server room.

4.4 Environmental Risks: The Uninsurable?

Site selection is further complicated by environmental factors.

● Flight Paths: Data centers cannot be placed directly under flight paths due to the vibration risk discussed in above. Sound waves from low-flying aircraft can disrupt HDD operations.

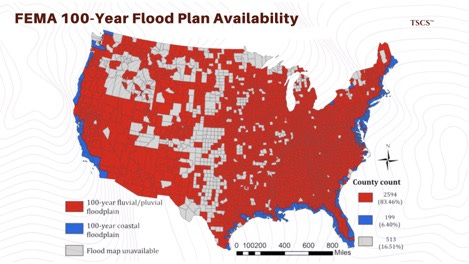

● Flood Risk: As climate risk reprices insurance, the “100-year floodplain” maps from FEMA are increasingly seen as outdated. Prudent operators are looking for “500-year” safety. Historical data (like Superstorm Sandy crippling Manhattan data centers) serves as a grim reminder that a basement fuel pump is the Achilles heel of a billion-dollar facility.

Section 5: Software

While hardware grabs headlines, a massive reallocation of budget is occurring in the software layer, triggered by Broadcom’s acquisition of VMware. This event has shattered the “default” status of the virtualization layer.

5.1 Broadcom/VMware Shock

Broadcom’s post-acquisition strategy, ending perpetual licenses, bundling products, and aggressively raising prices, has alienated the VMware customer base. For many CIOs, the “VMware tax” has become unsustainable, driving a search for alternatives.

5.2 The Beneficiaries: Nutanix and Red Hat

This friction is driving a migration to two primary alternatives:

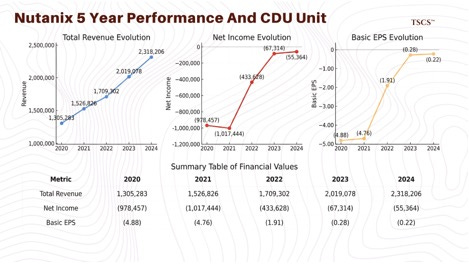

Nutanix (NTNX): Nutanix is the only true “full stack” alternative to VMware for traditional enterprise workloads, offering a hypervisor (AHV), software-defined storage, and management plane. Their financials reflect this influx: Nutanix’s free cash flow surged to $750 million in FY2025, a 25% year-over-year increase. They are capturing the “lift and shift” market, enterprises that want to leave VMware but aren’t ready to refactor their apps for containers.

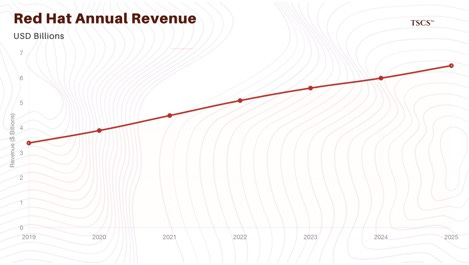

Red Hat (IBM): For cloud-native workloads, the shift is toward containers and Kubernetes. Red Hat OpenShift is the dominant enterprise Kubernetes platform. IBM reports that OpenShift annual recurring revenue (ARR) has hit $1.7 billion, with growth rates consistently in the double digits (growing ~14-20%). The acquisition of Red Hat has arguably “paid for itself” by giving IBM a sticky, high-growth revenue stream that sits at the heart of the hybrid cloud. Unlike RHEL (Linux), which grows steadily, OpenShift is the growth engine, effectively taxing the virtualization exodus.

Section 6: Reliability - Power Guarantee

A data center that cannot guarantee power continuity is, by definition, a distressed asset.

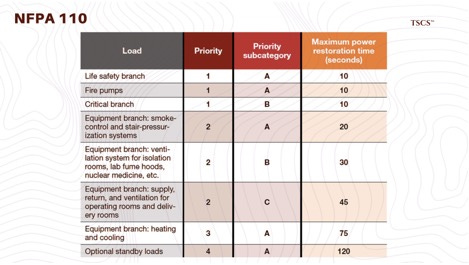

The Service Level Agreements (SLAs) governing these facilities often penalize downtime at rates of thousands of dollars per minute, but the reputational damage of a failure is incalculable. This section explores the two critical components that ensure this continuity: the prime mover (generators) and the switching mechanism (Automatic Transfer Switches).

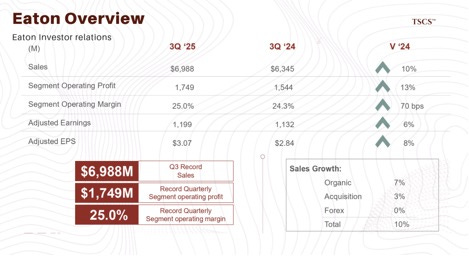

This is the job of Cummins (CMI) and Eaton (ETN).

6.1 Cummins (CMI): The Transient Response Moat

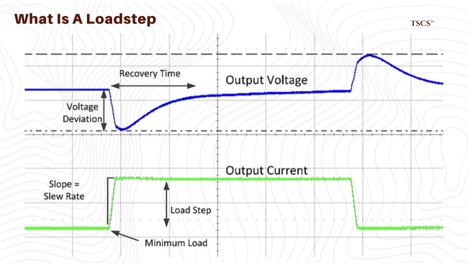

When utility power fails, the transition to backup is violent. The generator must accept the full site load, often megawatts, in a single step without causing frequency or voltage sags that would trip downstream UPS systems. This is the “100% load acceptance” imperative, and it is Cummins’ moat.

When load hits, electromagnetic resistance brakes the crankshaft, dropping engine RPM and therefore AC frequency. If frequency drops below 57-58 Hz, the UPS rejects the power source and switches to battery. If the generator cannot recover before batteries deplete, the data center goes dark.

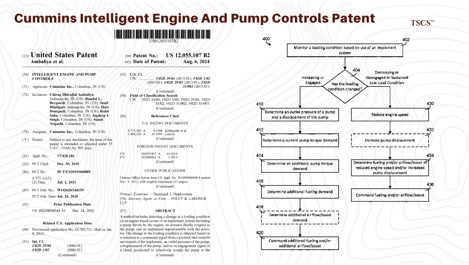

Cummins’ Centum Series addresses this through the QSK38 and QSK78 engine platforms, which use high-pressure common rail fuel injection and optimized turbocharging to minimize “turbo lag.” By reducing parasitic friction on the turbocharger rotor (via non-contact seal systems), the engine recovers boost pressure faster during transient events. The integrated engine control module can pre-emptively adjust fuel timing within milliseconds of detecting frequency deviation, creating a “stiff” power source that behaves more like the infinite inertia of the utility grid.

Caterpillar (CAT) competes primarily through oversized alternators that add rotational mass for stability. Both approaches work, but Cummins’ integrated turbo-fuel-ECM system offers faster reaction time, while Caterpillar’s is mechanically simpler.

The fuel question matters too. Natural gas generators have a lower carbon profile but depend on external pipeline infrastructure, which fails in earthquakes or major disasters. Diesel generators operate from on-site tanks, making them closed-loop systems independent of external infrastructure. Cummins hedges the carbon concern through HVO (Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil) compatibility, allowing operators to keep diesel’s reliability mechanics while decarbonizing the fuel source.

6.2 Cummins vs. Caterpillar

The primary rival in this space is Caterpillar (CAT). The research material presents a nuanced comparison between the two giants. Caterpillar’s marketing emphasizes fuel efficiency and ease of permitting. Their generators are renowned for meeting the ISO 8528-5 G3 performance class for load acceptance, which is the highest standard for commercial power.

However, the distinction often comes down to the alternator design and inertia. Caterpillar notes that “higher inertia improves the transient response,” and they achieve this by sometimes “oversizing the generator” (adding mass) to meet load rejection requirements.

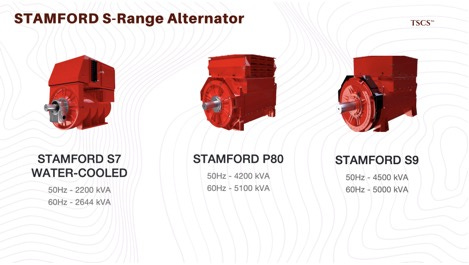

Cummins counters this with the STAMFORD S-Range alternator, which uses low reactance 2/3 pitch windings. This specific winding pitch is critical for data centers because it minimizes waveform distortion when handling non-linear loads (like the rectifiers in UPS units and server power supplies).

While Caterpillar relies on the sheer mass and displacement of its engines for stability, Cummins focuses on the integration of the turbocharger, fuel system, and digital controls to achieve a faster reaction time.

Both are formidable, but Cummins’ specific focus on the “100% load acceptance in a single step” for the Centum series targets the exact anxiety of data center operators: the fear of the “failed start.”

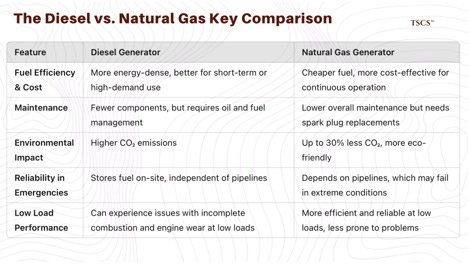

Diesel vs. Natural Gas

A critical aspect of the reliability discussion is the fuel source itself. There is a growing push for natural gas generators due to their lower carbon profile. However, the fundamentalist view favors diesel for critical backup, particularly in seismically active regions like the US West Coast (a major data center hub).

You 100% need diesel, you can not rely on NG.

The reasoning is based on first principles of infrastructure resilience. Natural gas relies on a continuous, pressurized supply from an external pipeline network. In the event of a major earthquake, gas mains often rupture or are automatically shut off by safety valves to prevent fires. A natural gas generator, no matter how efficient, is useless without fuel.

Diesel generators, conversely, operate with on-site fuel storage tanks (often “belly tanks” located beneath the unit). They are closed-loop systems independent of external infrastructure during a crisis. This autonomy is the primary reason why, despite the “green” narrative, diesel remains the gold standard for the “last line of defense” in Tier 4 data centers.

Cummins is hedging this carbon concern through HVO (Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil) compatibility. HVO is a paraffinic diesel fuel synthesized from renewable feedstocks that is chemically identical to petro-diesel but with significantly lower lifecycle carbon emissions. By certifying the Centum series for HVO, Cummins allows data center operators to keep the reliability mechanics of the diesel engine (compression ignition, on-site fuel, high torque rise) while decarbonizing the fuel source. This is a critical strategic pivot that maintains the relevance of their internal combustion IP in a decarbonizing world.

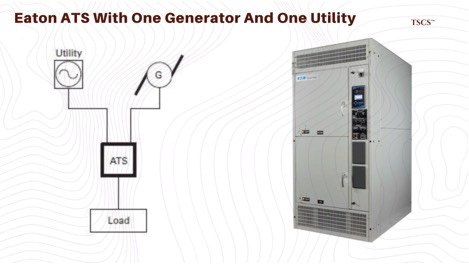

6.3 Eaton (ETN): The Single Point of Failure and ATS

Eaton’s position in this market is dominant, but the risks associated with ATS failure are often misunderstood and underpriced by the market.

The ATS is a device that monitors the utility power and, upon detecting a failure, signals the generator to start and mechanically switches the load from the utility bus to the generator bus. It is a single point of failure in the truest sense: if the ATS fails to switch, the generator running perfectly nearby is useless. The load remains connected to a dead grid, and the facility goes dark.

The Daisy-Chaining Risk and the eATS30 Solution

A nuanced insight from Eaton’s footnotes is the danger of “daisy-chaining” power protection devices to achieve redundancy. Operators often attempt to increase reliability by connecting multiple UPSs or switches in series. Eaton’s probability studies demonstrate that this actually increases the risk of failure by combining the failure rates of the two units. If you have two devices in series, and either fails, the circuit opens.

Eaton’s strategic response to this is the eATS30 Monitored platform. This rack-mounted ATS is designed for equipment with single power supplies (common in older or specialized network gear). Instead of daisy-chaining, the eATS30 provides dual-source redundancy at the rack level. It can switch between two power sources A and B in 10 milliseconds.

This 10ms transfer time is a critical specification. It is fast enough to be invisible to the IT load’s power supply unit (PSU) capacitors, which can typically ride through a power loss of 10-20ms. By moving the redundancy logic as close to the load as possible, Eaton reduces the “blast radius” of any single upstream failure.

Market Positioning

The North American ATS market is projected to grow at a CAGR of roughly 9.15%, driven by the increasing dependence on uninterrupted power. Eaton competes directly with ASCO (Schneider Electric) and Cummins in this space. However, Eaton’s advantage lies in its broader “Power Management” ecosystem.

Section 7: Management – Thermal & Digital Control

Reliability ensures the lights stay on; Management ensures the facility doesn’t bankrupt its operator through inefficiency. As data centers scale, the disconnect between the “logical” layer (applications, workloads) and the “physical” layer (power, cooling, space) becomes a primary source of inefficiency. Carrier (CARR) and ServiceNow (NOW) are converging to solve this problem.

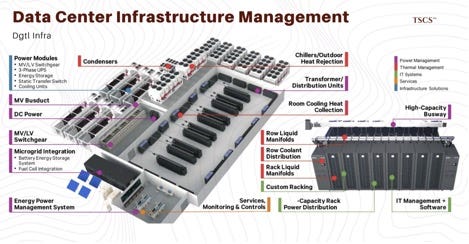

7.1 Carrier (CARR) & Nlyte

Carrier is historically known as an HVAC hardware manufacturer, chillers, air handlers, and compressors. However, its acquisition of Nlyte Software shifted its strategy from “making cold air” to “managing thermal lifecycles.”

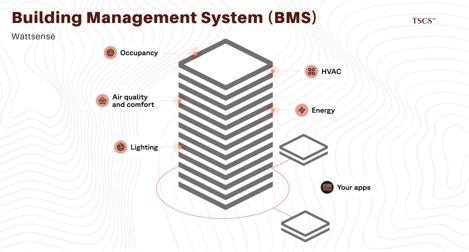

The DCIM + BMS Integration Thesis

Data centers have traditionally operated with two distinct brains that rarely communicate:

BMS (Building Management System): Controls the mechanical plant (chillers, pumps, fans). Carrier’s WebCTRL is a market leader here. It monitors physical parameters like water temperature and air pressure. It knows the temperature of the water leaving the chiller but knows nothing about the servers heating that water.

DCIM (Data Center Infrastructure Management): Manages the IT assets (servers, racks, PDUs). Nlyte is a leader here. It knows which server is in Rack 4, U-position 12, and what application it is running, but it has no direct control over the cooling system.

The integration of Nlyte with WebCTRL bridges this gap, creating Integrated Data Center Management (IDCM). This is a powerful “second-order” insight: by connecting the IT load (the demand) directly to the cooling plant (the supply), the system can react proactively rather than reactively.

Asset Lifecycle Management and “Ghost Servers”

Carrier’s Nlyte acquisition also addresses the “ghost server” problem. Without integration, the logical view (ServiceNow) and physical view (Nlyte) drift apart. This leads to servers that are running, consuming power, and requiring cooling, but are doing no useful work because they have been logically decommissioned but physically forgotten.

Nlyte’s Asset Optimizer automates the tracking of these assets, ensuring that every watt of cooling Carrier provides is directed at a revenue-generating asset. This transforms Carrier from a vendor of commodity hardware into a strategic partner in CapEx efficiency and sustainability tracking, a critical KPI for hyperscalers committed to net-zero goals.

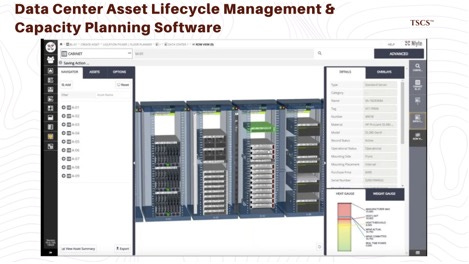

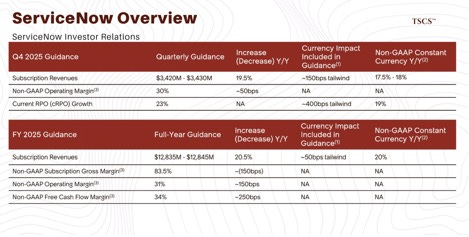

7.2 ServiceNow (NOW)

ServiceNow dominates IT Service Management, managing the “logical” layer (software, incidents, licenses). Its integration with Nlyte extends reach into the physical layer, creating a moat around operational workflow.

The value is bi-directional CMDB synchronization. When a change request (”Decommission Server X”) is approved in ServiceNow, it automatically triggers a workflow in Nlyte guiding the technician to the exact rack and U-position. When the technician completes the task in Nlyte, ServiceNow updates instantly.

This creates a single source of truth. Once a data center’s physical operational workflow (moves, adds, changes) is built on the ServiceNow-Nlyte bridge, switching costs become prohibitive. The integration locks in both vendors by automating the most labor-intensive part of data center management.

Section 8: KPIs Precision Cooling & Water Efficiency

As chip densities increase (driven by AI accelerators like NVIDIA’s H100), the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) of data centers are shifting. WUE (Water Usage Effectiveness) is becoming critical as water scarcity becomes a regulatory bottleneck. Modine, Vertiv, and Xylem are optimizing these physics to meet the new demands of high-performance computing.

8.1 Modine (MOD)

Modine, through its Airedale brand, has moved beyond simple metal-bending of CRAC (Computer Room Air Conditioning) units to become a software-defined cooling provider. The acquisition of Airedale has provided Modine with a foothold in the high-margin data center cooling market, distinct from its legacy vehicular thermal management business.

Cooling AI: Predictive vs. Reactive

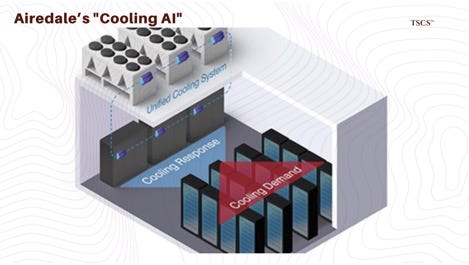

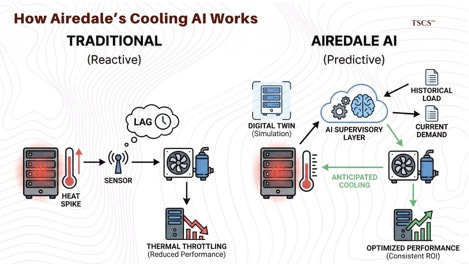

Airedale’s “Cooling AI,” a patent-pending technology that uses a hybrid deep learning model and digital twins. The fundamental insight here is the shift from reactive to predictive cooling.

A traditional cooling system operates on a feedback loop: a temperature sensor detects a rise in heat, and the system reacts by increasing fan speed or compressor output. This introduces a lag. By the time the cooling system ramps up, the server temperature may have already spiked, potentially causing the processors to throttle their clock speed to protect themselves. This thermal throttling reduces the computational performance of the cluster, a direct hit to the tenant’s ROI.

Airedale’s AI acts as a “supervisory layer” over the BMS. It analyzes historical load patterns and correlates them with current demand to anticipate heat spikes. It creates a “virtual proxy” or digital twin of the cooling network, allowing it to test optimization strategies in simulation before applying them to the physical equipment. This predictive capability is essential for handling the “bursty” nature of AI training workloads, where power consumption can jump dramatically in milliseconds.

8.2 Vertiv (VRT): The Water-Free Future (Liebert DSE)

Vertiv’s Liebert DSE system represents a masterclass in thermodynamic arbitrage. The central problem it solves is the industry’s reliance on water for evaporative cooling. Traditional cooling towers are thermodynamically efficient because they use the latent heat of evaporation to reject heat. However, they consume millions of gallons of water annually, a massive liability in drought-prone regions like California or Arizona, where water permits are becoming as difficult to obtain as power connections.

The Pumped Refrigerant Economizer

The Liebert DSE uses a pumped refrigerant economizer (marketed as EconoPhase). In standard operation (DX mode), a compressor compresses the refrigerant gas to reject heat, which is energy-intensive. However, when the outside air is cool enough, the DSE system switches to “economizer mode.”

In this mode, the energy-hungry compressors are turned off. Instead, a low-power liquid pump circulates the refrigerant. The refrigerant absorbs heat from the data center and rejects it to the outside air purely through the temperature differential, aided by the pump. This is similar to a “thermosyphon” effect but boosted by the pump to ensure consistent flow rates.

Unlike a water-side economizer (free cooling chiller), this system uses no water. It keeps the outside air completely separated from the data center air (preventing contamination) and eliminates the need for water treatment, blowdown, and sewage infrastructure.

“Save an average of 4 million gallons of water annually compared to chilled water systems.”

In a regulatory environment where water usage is under intense scrutiny, the Liebert DSE offers a “regulatory bypass” that is incredibly valuable. It allows data centers to be built in water-stressed regions without drawing the ire of local municipalities or environmental groups.

8.3 Xylem (XYL) / Evoqua

While Vertiv eliminates water usage for some, vast installed bases of water-cooled chillers exist and will continue to be built where ambient air temperatures are too high for air cooling. Xylem, through its acquisition of Evoqua, optimizes this water usage. Their strategy focuses on greywater treatment and microsand filtration.

Vortisand and the 5-Micron Battle

Evoqua’s Vortisand technology attacks the inefficiency of cooling towers at the microscopic level. Cooling towers are essentially giant air scrubbers; they pull in dust, pollen, and debris from the outside air. This debris accumulates in the water and fouls the heat exchangers (chiller tubes). A fouled tube transfers heat poorly, forcing the chiller to work harder and raising energy costs (worsening PUE).

“85 percent of the particles in cooling tower water samples measure under 5 microns.”

Traditional sand filters cannot catch particles this small; their limit is often 20-30 microns. Vortisand, using a specialized cross-flow microsand filtration technique, can trap these sub-5-micron particles.

By removing these fine particulates, the system deprives bacteria of a surface to attach to, inhibiting biofilm formation. Biofilm is a potent insulator, 4 times more resistant to heat transfer than calcium scale. By keeping the water free of biofilm, Xylem ensures that the chiller operates at its design efficiency, effectively recovering capacity that would otherwise be lost to fouling.

Greywater Patents and Water Circularity

Xylem is also pioneering the use of greywater (wastewater from sinks, showers, or industrial processes) for cooling. Patent data suggests Xylem/Evoqua is developing intellectual property around “chemical-free cooling towers” and greywater draining/harvesting. This allows data centers to use non-potable water for cooling, a critical requirement in jurisdictions that ban the use of drinking water for industrial cooling.

The integration of UV disinfection (Evoqua’s ETS-UV) with filtration replaces chemical biocides. This is significant because chemically treated water is difficult to discharge; it often requires neutralization before it can be sent to the sewer. By using physical disinfection (UV) instead of chemical disinfection, the “blowdown” water is cleaner and easier to dispose of or recycle, furthering the goal of water circularity.

Section 9: Critical Materials (Transformers, Steel, Fluids)

9.1 HD Hyundai vs. Hitachi

The market is dominated by a few players who are scrambling to expand capacity, but the physical reality of building these heavy industrial assets means relief is slow to arrive.

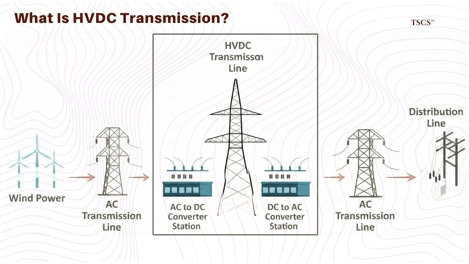

HD Hyundai Electric: Is investing $274 million to expand capacity at its Alabama and Ulsan plants by 30%. They are explicitly targeting the North American market, even building storage facilities to hold finished units. Their partnership with Hitachi Energy on HVDC (High Voltage Direct Current) transformers in Korea signals a strategic move into long-distance transmission technology. HVDC is vital for the “Energy Expressway,” connecting remote renewable sources to data center hubs with lower transmission losses than traditional AC lines.

Hitachi Energy: Is investing heavily ($270M CAD in Canada, $150M in Charlotte, NC) to triple capacity. The Charlotte facility is a key strategic asset for serving the US market.

9.2 Siemens Energy: Also expanding with a $150M factory in Charlotte.

The insight here is that capacity is not elastic. You cannot simply “spin up” a transformer factory. It requires specialized winding machines, massive vacuum drying chambers to remove moisture from the insulation, and highly skilled labor. The players with existing footprints and active expansion projects (like Hyundai and Hitachi) have immense pricing power for the next 3-5 years. The “150-week” moat protects their margins.

9.3 Cleveland-Cliffs (CLF): The Material Monopoly

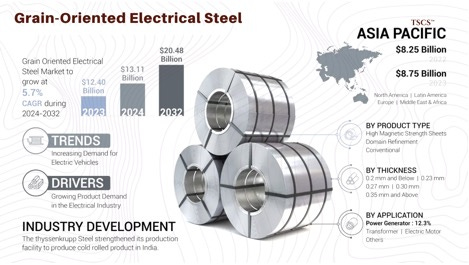

Downstream of the transformer manufacturers lies an even tighter bottleneck: Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel (GOES). Transformers rely on the magnetic properties of GOES to function efficiently. The steel must be processed to align its crystalline structure in the direction of the rolling, minimizing hysteresis loss (energy lost as heat during magnetization cycles).

Cleveland-Cliffs is the sole producer of GOES in the United States. This is a classic monopoly moat. The Butler Works facility in Pennsylvania is a strategic national asset. Without it, the US grid is entirely dependent on imported electrical steel, which faces tariffs and logistics hurdles (the “Mexico pit stop” mentioned by CEO Lourenco Goncalves in refers to competitors rerouting steel through Mexico to avoid tariffs).

Cleveland-Cliffs holds the most unassailable domestic moat. Globally, GOES is produced by Nippon Steel, JFE, POSCO, and Baowu. The moat is regulatory (tariffs, Buy America provisions) rather than technological. If trade policy shifts or hyperscalers build in Europe/Asia, the moat narrows

9.4 Solvay vs. Chemours

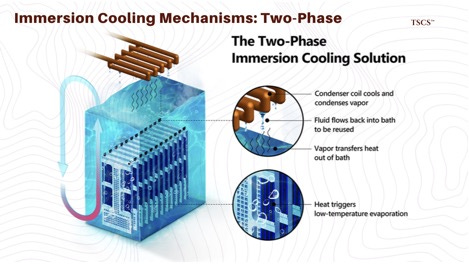

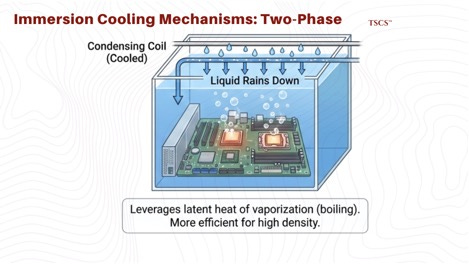

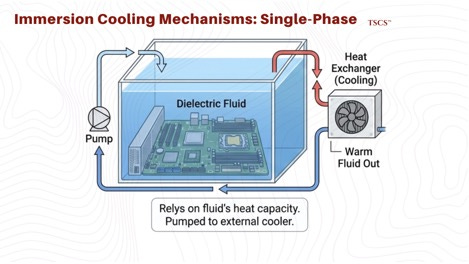

The final piece of the infrastructure puzzle is the fluid itself. As air cooling hits its physical limits (generally around 30-40 kW per rack), the industry is moving toward immersion cooling, where servers are submerged in a thermally conductive but electrically insulating (dielectric) liquid.

The market was thrown into chaos by 3M’s decision to exit the PFAS market and discontinue its Novec and Fluorinert lines by the end of 2025. Novec was the industry standard for 2-phase immersion cooling. Its exit creates a massive vacuum that Solvay and Chemours are racing to fill.

9.5 The Contenders: Opteon vs. Galden

Chemours (Opteon SF80): Chemours is pushing its Opteon line of 2-phase immersion cooling fluids (HFOs). They have secured a major qualification with Samsung Electronics for SSD cooling.

Solvay (Galden): Solvay is positioning its Galden PFPE fluids as the direct drop-in replacement for Novec. Galden has a long history in semiconductor testing and offers high thermal stability.

The physics trade-off is 2-phase vs. single-phase. In 2-phase systems (Chemours), the fluid boils at the chip surface (~50°C), absorbing massive energy via latent heat of vaporization. The vapor rises, condenses on a coil, and rains back down. This enables extremely high heat rejection density with passive circulation. The downside: hermetically sealed tanks (expensive) and regulatory risk from fluorinated chemistry.

In single-phase systems (oils, or Galden in liquid state), the fluid does not boil. It is pumped across chips to remove heat via convection. Simpler tank design, cheaper fluids, but less efficient heat transfer and mechanical pump failure risk.

Chemours has the edge in high-performance segments due to Samsung validation. However, the PFAS regulatory overhang remains a critical risk for all fluorinated fluids, potentially opening the door for hydrocarbon-based oils (Shell, Fuchs) long-term.

Section 10: Memory (The HBM War)

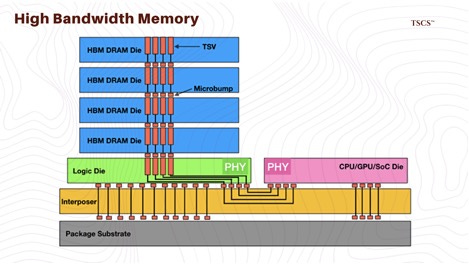

The bottleneck in AI training and inference is no longer just compute (FLOPS); it is memory bandwidth. The GPU is a hungry beast, and if it cannot be fed data fast enough, it idles. This reality has elevated High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) from a niche component to the single most critical variable in the bill of materials (BOM) for AI accelerators. However, the equity market’s understanding of HBM is often limited to capacity (gigabytes) rather than the process engineering (packaging yield) that dictates profitability.

10.1 MR-MUF vs. TC-NCF

SK Hynix has established a structural lead through its proprietary Advanced MR-MUF (Mass Reflow Molded Underfill) process. In this process, the stacked chips are reflowed (heated) simultaneously, and a liquid molding compound is injected to fill the gaps between the dies. The key advantage here is thermal dissipation. As memory stacks grow from 8 to 12 and eventually 16 layers, the heat trapped within the vertical stack becomes a critical failure point. MR-MUF allows for better heat management because the molding compound has superior thermal conductivity compared to traditional films. This process has proven superior in yield stability for 12-layer stacks, which are the current standard for Nvidia’s H100 and H200 series.

Conversely, Samsung stubbornly adhered to TC-NCF (Thermal Compression Non-Conductive Film). This method involves placing a non-conductive film between layers and using thermal compression to bond them. While theoretically sound, in practice, NCF limits the number of thermal bumps (pathways for heat to escape) and is more prone to warping during the bonding of high-layer-count stacks. The result has been catastrophic for Samsung’s qualification timelines. While SK Hynix secured the position as Nvidia’s primary supplier with nearly 90% market share in the early HBM3 cycle , Samsung struggled with consistency and output, slipping to third place in the overall HBM market behind Micron in Q2 2025.

This is a classic case of “Process Alpha.” SK Hynix’s valuation premium is justified because their process allows for higher effective margins. HBM consumes three times the wafer capacity of regular DRAM , meaning that yield loss is three times as punitive to return on invested capital (ROIC). Every wafer lost to warping or thermal failure in the TC-NCF process is a massive hit to the bottom line, whereas SK Hynix’s higher yields translate directly to free cash flow.

10.2 The Micron Incursion: Efficiency as a Weapon

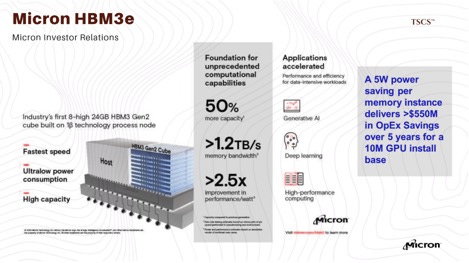

While the Korean giants battle over packaging methodologies, Micron Technology (MU) has entered the fray with a distinct value proposition: power efficiency. Micron’s HBM3E product is verified to be 30% more power-efficient than SK Hynix’s current offering.

In the context of an AI data center, where power availability is the hard cap on growth, a 30% reduction in memory power consumption is not a “nice-to-have”; it is a massive Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) lever. It allows hyperscalers to deploy more compute within the same power envelope. Micron has confirmed that their HBM capacity is sold out for 2024 and most of 2025 , and they expect an annualized revenue run-rate from HBM to hit $8 billion.

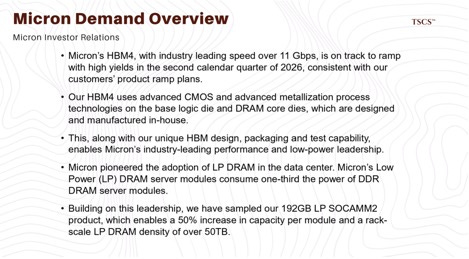

However, the contrarian caution here is “Wait for Qualification.” While Micron claims superiority, the market share data for Q2 2025 shows them at 21%, significantly behind SK Hynix’s 62%. The “lag” in revenue recognition suggests that while the product is technically superior, the ramp-up of manufacturing yield at scale is the actual constraint. Micron’s valuation (P/E ~14x forward) reflects this uncertainty , but if they can prove yield stability, the efficiency argument will force Nvidia and AMD to allocate more volume their way.

10.3 HBM4 Inflection

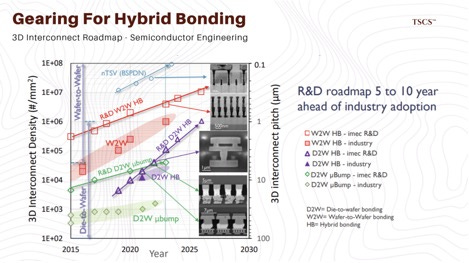

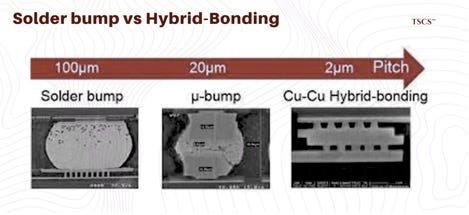

The market is currently pricing current market share, but the smart money is looking at the HBM4 transition in 2026. This generation marks a fundamental discontinuity in manufacturing: the shift to Hybrid Bonding.

Hybrid Bonding eliminates the micro-bumps entirely, bonding copper directly to copper. This reduces the stack height, improves electrical efficiency, and allows for 16-layer and eventually 20-layer stacks. Samsung is aggressively pivoting to Hybrid Bonding for HBM4, hoping to leapfrog SK Hynix. SK Hynix, meanwhile, is refining MR-MUF but also preparing for Hybrid Bonding.

Thesis: The transition to Hybrid Bonding flattens the playing field. SK Hynix’s MR-MUF advantage becomes less relevant if the industry standardizes on bump-less bonding. This reintroduces execution risk for SK Hynix and offers Samsung a “fighting shot” to regain share. For the investor, this means the SK Hynix premium may compress sometime in 2026 as the market anticipates the HBM4 “war of nerves”.

Moreover, the rise of “Custom HBM” , where logic is integrated into the memory stack, suggests a future where memory makers and foundries (TSMC) must collaborate even more closely. This benefits players with strong foundry alliances.

10.4 Semiconductor Equipment

The yield advantages discussed above are not purely process IP; they depend entirely on lithography and packaging equipment. Four companies sit upstream of every chip in this primer.

ASML Holding (ASML) holds an absolute monopoly on extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, the machines that pattern features below 7nm. Every HBM controller die, every Nvidia GPU, every Broadcom ASIC, every AMD MI300 flows through ASML tools. There is no second source. The different approach to high-NA EUV, now entering production, will determine which fabs can manufacture the next generation of AI silicon. ASML’s backlog exceeds €36 billion, and lead times stretch beyond 18 months.

Applied Materials (AMAT) and Lam Research (LRCX) dominate the deposition and etch steps critical for advanced packaging. The HBM stacking process, the through-silicon vias (TSVs) that connect memory layers, the hybrid bonding that will define HBM4, all require their tools. Applied Materials holds particular strength in the metal deposition steps that form the copper interconnects.

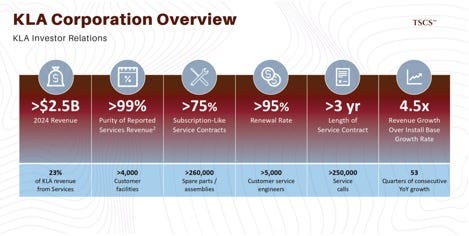

KLA Corporation (KLAC) provides metrology and inspection. In a world where HBM yield is the primary determinant of profitability, catching defects before they propagate through a 12-layer stack is existential. KLA’s tools scan wafers at every critical step, flagging anomalies that would otherwise destroy entire production lots.

No Chinese competitor has successfully replicated EUV. No alternative exists for leading-edge metrology. The semicap oligopoly is, in many ways, tighter than the chip oligopoly it enables.

Section 11: Optics (Photonic Fabric)

As GPU clusters scale from thousands to hundreds of thousands (e.g., the 100k GPU cluster planned by Microsoft/OpenAI), the latency of electrical copper cables becomes unacceptable. We are entering the era of the Optical Interconnect.

11.1 Fabrinet

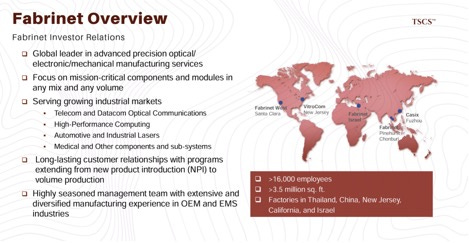

Fabrinet (FN) has long been the darling of the optical sector, primarily due to its position as the sole-source manufacturer for Nvidia’s optical transceivers (via the NVLink backbone). The company reported record revenue in Q1 2026, driven by datacom demand , and is actively ramping 1.6T transceivers for the Blackwell Ultra platform.

The bull case is simple: Fabrinet is the manufacturing arm of Nvidia’s networking division. As Nvidia grows, Fabrinet grows. They handle complex assembly that requires extreme precision, active alignment of lasers and lenses, which is difficult to automate and relies on low-cost, high-skill labor in Thailand.

However, the contrarian view flags a massive risk: Vendor Diversification. Innolight, a Chinese competitor, has claimed the top spot in global optical transceiver supply according to LightCounting. More critically, reports suggest Nvidia is diversifying its supply chain for the 2026 ramp, with Innolight and Eoptolink securing up to 60% of the 800G/1.6T orders.

This is a structural deterioration of Fabrinet’s moat. While Fabrinet is a “contract manufacturer” (CEM) and Innolight is a transceiver vendor (design + build), the result for the end-client is the same. If Nvidia qualifies a second source that offers comparable performance at a lower cost, Fabrinet’s pricing power, and its valuation multiple, will compress. The market is currently pricing Fabrinet as a high-growth tech stock (Forward P/E ~27x) , but if it loses its sole-source status, it risks being repriced as a standard EMS (Electronics Manufacturing Services) provider.

This apparent contradiction resolves when you consider TAM expansion: the total addressable market for high-speed transceivers is growing faster than Fabrinet’s share loss. But this is a red flag. Share loss in a growing market eventually catches up.

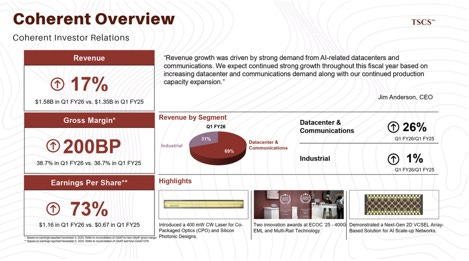

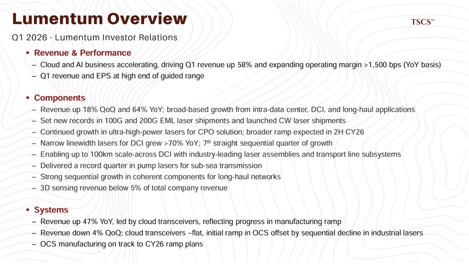

11.2 The Lumentum vs. Coherent Duopoly

Upstream from the assemblers are the component makers: Lumentum (LITE) and Coherent (COHR). These companies make the lasers (EMLs, VCSELs) that generate the light.

Coherent is the volume leader with ~25% market share and a vertically integrated model. They manufacture wafers, lasers, and finished transceivers. This vertical integration protects margins but exposes them to inventory cycles. Lumentum, by contrast, is the “specialized engineer,” focusing on high-performance Indium Phosphide (InP) chips.

The battleground here is the 1.6T and 3.2T generation. At these speeds, traditional materials struggle. Lumentum’s bet is that their advanced InP capabilities are essential for the high-power lasers required by new architectures. However, Coherent is aggressively pushing 800G and 1.6T transceivers, claiming mind share leadership.

For the investor, Coherent offers stability and scale, acting as the “industrial factory” of the sector. Lumentum is a higher-beta play on technological leadership in raw laser physics. Given the insatiable demand for bandwidth, both are poised for growth, but Lumentum’s focus on the chip rather than the module may insulate it better from the Chinese module competition (Innolight) that hurts Fabrinet.

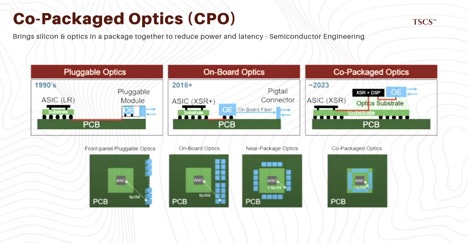

11.3 The Existential Threat: Co-Packaged Optics (CPO)

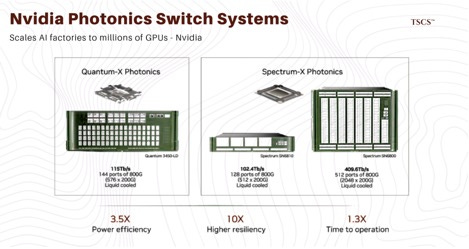

Looming over the entire sector is the transition to Co-Packaged Optics (CPO). Currently, optics are “pluggable” modules at the edge of the switch. CPO moves the optical engine directly onto the switch ASIC package, eliminating copper traces entirely.

Nvidia’s Spectrum-X and Quantum-X platforms are already integrating CPO concepts. This is a deflationary technology for the traditional supply chain. If the optics are integrated by TSMC or Nvidia directly (using engines from varying suppliers), the value-add of the external transceiver assembler (Fabrinet) evaporates. Fabrinet is trying to pivot by positioning itself as a CPO assembler , but the complexity of CPO favors semiconductor foundries (TSMC) over traditional EMS providers.

Section 12: Custom Silicon (ASIC)

While Nvidia dominates the merchant market for AI training, the hyperscalers (Google, AWS, Microsoft) are trying to decouple themselves from the “Nvidia Tax” by designing their own Application Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs).

The unstated concentration risk across this entire value chain is TSMC. Every Nvidia GPU, every Broadcom ASIC, every SK Hynix HBM controller die flows through fabs in Taiwan. Geopolitical disruption would be catastrophic and largely unhedgeable.

12.1 Broadcom

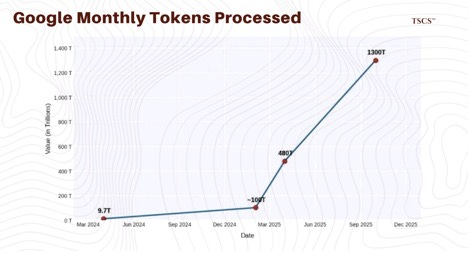

Broadcom (AVGO) is the undisputed king of this domain. They are the exclusive partner for Google’s TPU (Tensor Processing Unit), which has now reached its 7th generation (”Ironwood”). The volume is huge: Google’s token processing jumped from 480 trillion to 1,300 trillion in six months.

Broadcom’s moat is its SerDes (serializer/deserializer, the technology that converts parallel data to serial for high-speed transmission). This IP is so critical that Broadcom has effectively locked in Google and is rumored to be the partner for OpenAI’s custom chip (”Titan”).

The contrarian insight here is that Broadcom is actually an AI infrastructure play disguised as a semiconductor company. With a potential $150 billion revenue opportunity from OpenAI alone , Broadcom’s custom silicon business acts as a hedge against Nvidia. If Nvidia’s margins compress because hyperscalers succeed in building their own chips, Broadcom wins. If Nvidia stays dominant, Broadcom still wins via its networking/switching monopoly (Jericho/Tomahawk chips).

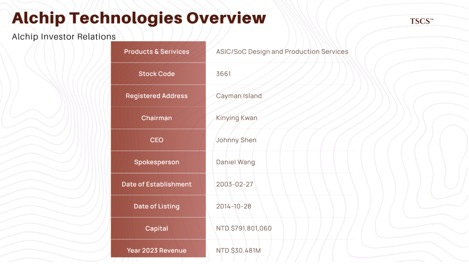

12.2 Alchip and Marvell: The Challengers

Alchip Technologies is the AWS proxy. As the key design partner for AWS (likely Inferentia/Trainium), Alchip has seen meteoric growth. However, it trades with “customer concentration risk.” When Alchip reported a revenue miss, the stock fell, despite the long-term thesis remaining intact. This volatility is characteristic of the ASIC “contractor” model. Unlike Broadcom, which owns the IP, Alchip is more of a high-end design service.

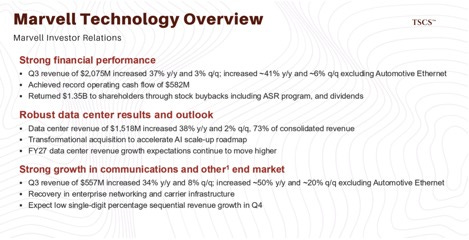

Marvell Technology (MRVL) occupies the middle ground. They are the partner for Amazon’s Trainium 2 and Microsoft’s Maia. Marvell’s valuation is high (EV/EBITDA ~49x) , pricing in perfection. The risk for Marvell is that it is “whipsawed” by the CapEx cycles of these hyperscalers. Unlike Broadcom’s entrenched TPU relationship, Marvell’s wins feel more transactional and subject to competitive displacement by Alchip or internal hyperscaler teams.

Section 13: Power & Grid (The Electron Supply Chain)

The most undervalued risk in the data center value chain is not technology; it is Permitting. The US electrical grid is out of capacity in key hubs (Northern Virginia), and the timeline to build new transmission lines is 5-10 years.

13.1 Nuclear & FERC

The “Nuclear AI” trade exploded in 2025. Constellation Energy (CEG) signed a 20-year Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with Microsoft to restart Three Mile Island Unit 1 (Crane Clean Energy Center). Talen Energy (TLN) sold a campus to Amazon at the Susquehanna nuclear plant.

Hyperscalers need 24/7 carbon-free power (baseload), and nuclear is the only source that provides it at scale. By “co-locating” the data center behind the meter (directly connected to the plant), they bypass the grid and the transmission fees.

The Contrarian Pivot: On November 1, 2024, FERC rejected the amended Interconnection Service Agreement (ISA) for the Amazon/Talen Susquehanna deal. The grid operators (PJM) and utilities (AEP, Exelon) argued that co-location shifts transmission costs to other ratepayers and threatens reliability.

This is a massive signal. It means the “easy button” of plugging data centers directly into nuclear plants is effectively broken or severely limited. It caps the upside for Talen Energy’s co-location strategy and forces hyperscalers back onto the grid.

Implication: This could be bullish for Vistra Corp (VST) and Constellation (CEG) in a different way. If co-location is hard, hyperscalers must sign Virtual PPAs (VPPAs) and pull from the grid. This tightens the overall supply/demand balance of the grid, driving up wholesale power prices. Vistra and Constellation, as merchant generators with open capacity, benefit from higher power prices across the board, not just from specific data center deals.

13.2 REIT

In the real estate sector, Digital Realty (DLR) and Equinix (EQIX) are the titans. Digital Realty is the wholesaler (big megawatts), Equinix is the retailer (connectivity).

Digital Realty is seeing a resurgence. Their backlog has hit $852 million , and renewal spreads are healthy (8% cash, 11.5% GAAP). They have power capacity in Northern Virginia, the most constrained market in the world. In a supply-constrained market, the landlord with available power holds all the cards.

Iron Mountain (IRM) is the surprise contender. Known for paper storage, their “Project Matterhorn” pivot to data centers is real. They are expanding aggressively in Virginia (200MW+ campus). Because they are converting existing industrial footprint and have strong relationships with government/compliance-heavy clients, they have a unique angle. Their valuation (EV/EBITDA ~20x) is cheaper than Equinix (~24x) and Digital Realty (~27x) , offering a “growth at a reasonable price” (GARP) entry into the sector.

We don’t recommend REITs for Data Centers.

Conclusion: The Alpha is in the Bottlenecks

The data center value chain is a series of bottlenecks, each with its own physics, its own lead times, and its own competitive dynamics.

Memory: SK Hynix’s MR-MUF process advantage is real and reflected in their ~62% HBM market share. But the HBM4 transition to hybrid bonding in 2026 flattens the playing field. Watch Samsung’s yield data like a hawk. If they execute, the SK Hynix premium compresses.

Optics: Fabrinet is excellent but crowded and losing share. The risk/reward favors upstream component suppliers (Coherent, Lumentum) or the inevitable CPO disruptors (Broadcom, TSMC) over the contract assemblers. The “pluggable” era has a shelf life.

Power: The “Nuclear Co-location” thesis took a bullet from FERC. The interconnection queue is a moat for those already connected.

Cooling: Vertiv is the safe bet with regulatory moat (water-free cooling). Modine offers better valuation for similar exposure to the thermodynamic inevitability of liquid cooling. The market underestimates how much of AI capex flows to thermal management.

Materials: Cleveland-Cliffs’ GOES monopoly is domestic and regulatory, not global and technological. But in a world of tariffs, Buy America mandates, and 150-week transformer lead times, “domestic” is what matters.

Equipment: ASML, Applied Materials, Lam Research, and KLA sit upstream of everything. They are the true “picks and shovels,” capacity-constrained and backlog-rich. The semicap oligopoly is tighter than the chip oligopoly it enables.

The market prices GPUs. The smart money prices the transformer lead time, the HBM yield curve, the FERC docket, and the powered square footage in Ashburn.

The “AI Trade” of 2026 is about buying the heat sink, the photon, the electron, and the concrete that makes the chip possible.

We’ll soon analyze the valuation spreads across this value chain and identify the most mispriced links.

Disclaimer: The information provided on this Substack is for general informational and educational purposes only, and should not be construed as investment advice. Nothing produced here should be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security.

Brilliant breakdown of the virtualization layer shift. The observation about hypervisors becoming overhead for AI workloads really nails somethign I've been seeing in practice. When we moved our training clusters from VMware to bare-metal Kuberentes, latency dropped by almost 15% and we reclaimed like 8% of our GPU cycles that were just getting burned on abstraction layers. The Broadcom pricing disaster is basically accelerating what woud've happened anyway, but nobody wants to admit the hypervisor tax was always kinda absurd for compute-bound stuff.